Film noir (/fɪlm nwɑr/; French pronunciation: [film nwaʁ]) is a cinematic term used primarily to describe stylish Hollywood crime dramas, particularly those that emphasize cynical attitudes and sexual motivations. Hollywood’s classical film noir period is generally regarded as extending from the early 1940s to the late 1950s. Film noir of this era is associated with a low-key black-and-white visual style that has roots in German Expressionist cinematography. Many of the prototypical stories and much of the attitude of classic noir derive from the hardboiled school of crime fiction that emerged in the United States during the Great Depression.

(More on Film Noir from Wikipedia below)

Speaking as a big fan of Polanski, I know precisely what it is about his style of direction that attracts me. It is this: he accesses parts of the human psyche that most directors go nowhere near. As an actor and director, few can push the boundaries of uneasiness better than Polanski, though David Lynch is undoubtedly up there.

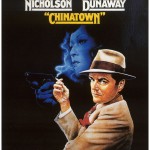

Chinatown is Polanski’s film noir in full colour, but it is almost a Greek tragedy in outlook. You can tell it’s noir by the sharp suits and the chain smoking, without looking further, though whether this is a cinematic landmark, “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant,” as defined by the Library of Congress in preserving the movie within its National Film Registry, or merely a frothy confection like candy floss, I leave to your imagination.

Set in 1937, Chinatown flirts with homage but is argued by critics to be a landmark in the late neo-noir movement, possibly so called because genuine noir is often applied to a specific period. However, in the classical Polanski mould, the noir style and substance is entirely by design. The style is honed, authentic and the mood ironic, almost sardonic; it is the noir cynicism with which the piece is slotted that makes Chinatown (which at no point actually features images of Chinatown, though the area is mentioned quite a lot) a perfect example of its genre.

The plot itself is in essence a comparatively simple mystery with a touch of psychological thriller thrown in for good measure. It is layered like a wedding cake and imbued with noirish twists and turns to keep the audience on its respective toes. As a plot alone is not exceptional – but then there never was anything particularly exceptional about the plots of noir classics. For the record this example uses as its source the water supply to LA:

A woman identifying herself as Evelyn Mulwray (Ladd) hires private investigator J.J. “Jake” Gittes (Nicholson) to perform surveillance on her husband Hollis I. Mulwray (Zwerling), the chief engineer for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. Gittes tails him, hears him publicly oppose the creation of a new reservoir, and shoots photographs of him with a young woman (Palmer) that are published on the front page of the following day’s paper. Upon his return to his office, Gittes is confronted by a beautiful woman who, after establishing that the two of them have never met, irately informs him she is Evelyn Mulwray (Dunaway) and that he can expect a lawsuit.

Realizing he was set up, Gittes figures whoever did it wants to get Mulwray, but, before he can question the husband, Lieutenant Lou Escobar (Lopez) fishes Mulwray, drowned, from a freshwater reservoir. Suspicious of murder, Gittes investigates and notices that, although huge quantities of water are released from the reservoir every night, the land is almost completely dry. He is confronted by Water Department Security Chief Claude Mulvihill (Jenson) with a henchman (Polanski) who slashes Gittes’s nose. Back at his office, Gittes receives a call from Ida Sessions, an actress whom he recognizes as the bogus Mrs. Mulwray. She is afraid to identify her employer, but provides a clue: the name of one of “those people” is in that day’s obituaries.

Gittes learns that Mrs. Mulwray’s husband was once the business partner of her father, Noah Cross (Huston), so he meets Cross for lunch at his personal club. Cross offers to double Gittes’ fee to search for Mulwray’s missing girlfriend, plus a bonus if he succeeds. Gittes visits the hall of records where he discovers that many large orange groves have recently changed ownership in the northwest San Fernando Valley. He goes there but is caught and beaten by angry landowners, who believe he is one of the water department agents who have been demolishing their water tanks and poisoning their wells to force them out.

Gittes’s review of the obituaries uncovers a former resident of the Mar Vista Inn, a retirement home, who is one of the new landowners in the Valley. He infers that Mulwray was murdered when he learned that the new reservoir would be used to irrigate the newly purchased properties. Evelyn and Gittes bluff their way into Mar Vista and confirm that the real estate deals are done in the name of its residents without their knowledge. After fleeing from Mulvihill and his thugs, they hide at Evelyn’s house, where they nurse each other’s wounds and end up in bed together.

Early morning, Evelyn has to leave suddenly, but she warns him that her father is dangerous and crazy. Gittes manages to follow her car to a house where he observes her with Mulwray’s girlfriend. He confronts Evelyn, who finally confesses that the woman is her sister.

The next day, an anonymous call draws Gittes to Ida Sessions’ apartment; he finds her murdered, with Escobar waiting for his arrival. Escobar pressures him because the coroner’s report found salt water in Mulwray’s lungs, indicating that the body was moved after death. Escobar suspects Evelyn of the murder, and insists Gittes produce her quickly or he’ll face charges of his own.

Gittes returns to Evelyn’s mansion. There he discovers a pair of bifocals in her salt water garden pond and finds her servants packing her bags. His suspicions aroused, he confronts Evelyn about her “sister”, whom she then claims is her daughter Katherine. Gittes slaps her repeatedly until she cries out “She’s my sister and my daughter!”, then tearfully asks Gittes if it is “too hard” for him to understand what happened with her father. She points out that the eyeglasses are not her husband’s, as he did not wear bifocals.

Gittes makes plans for the two women to flee to Mexico. He instructs Evelyn to meet him at her butler’s home in Chinatown. Gittes summons Cross to the Mulwray home to settle their deal for the girl. Cross admits he intends to incorporate the Northwest Valley into the City of Los Angeles, then irrigate and develop it. Gittes produces the bifocals—they belong to Cross and link him to Mulwray’s murder. Mulvihill appears, confiscates the glasses, and forces Jake to take them to the women.

When the three reach the hiding place in Chinatown, the police are already there and arrest Gittes. Evelyn will not allow Cross to approach Katherine, and when he is undeterred she shoots him in the arm and drives away with Katherine. As the car speeds off, the police open fire, killing Evelyn. Cross clutches Katherine and leads her away, while Escobar orders Gittes released, along with his associates. One of them urges, “Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown.”

It captures the ambience of its time in aspic, a period piece. So does the relationship between the two principle protagonists, which in modern idiom might be described as sexist and involve bullying and abusive, but is certainly typical of noir and has more complex facets within the subtext. And who better to share the iconic neo-noir status than two iconic actors: Jack Nicholson and Faye Dunaway, not to mention an iconic movie director, John Huston, doing a stint as acting?

All three do a splendid job, as does Polanski himself – yes, that’s him, the little guy in the cream suit and bow tie, slicing Nicholson’s nose. He gives himself all the memorable cameos, and even starring roles if you look at his edgy clerk in the spookily macabre The Tenant.

On my 3-scale classification of movies (those I wouldn’t touch with a barge-pole, those I would watch once, and those I would watch repeatedly), Chinatown hovers between the last two, though I think every intelligent movie-goer should watch it at least once. I’ve probably managed half a dozen viewings now over a period of maybe 35 years, which negates my previous comment but puts it below the status of, for example, Amadeus, which I could watch every day for a year without any loss of fascination.

Meanwhile, more on noir:

The term film noir, French for “black film,” first applied to Hollywood films by French critic Nino Frank in 1946, was unrecognized by most American film industry professionals of that era. Cinema historians and critics defined the category retrospectively. Before the notion was widely adopted in the 1970s, many of the classic films noirs were referred to as melodramas. Whether film noir qualifies as a distinct genre is a matter of ongoing debate among scholars.

Film noir encompasses a range of plots: the central figure may be a private eye (The Big Sleep), a plainclothes policeman (The Big Heat), an aging boxer (The Set-Up), a hapless grifter (Night and the City), a law-abiding citizen lured into a life of crime (Gun Crazy), or simply a victim of circumstance (D.O.A.). Although film noir was originally associated with American productions, films now so described have been made around the world. Many pictures released from the 1960s onward share attributes with film noir of the classical period, and often treat its conventions self-referentially. Some refer to such latter-day works as neo-noir. The clichés of film noir have inspired parody since the mid-1940s.

The questions of what defines film noir and what sort of category it is provoke continuing debate. “We’d be oversimplifying things in calling film noir oneiric, strange, erotic, ambivalent, and cruel”: this set of attributes constitutes the first of many attempts to define film noir made by French critics Raymond Borde and Etienne Chaumeton in their 1955 book Panorama du film noir américain 1941–1953 (A Panorama of American Film Noir), the original and seminal extended treatment of the subject. They emphasize that not every film noir embodies all five attributes in equal measure—one might be more dreamlike; another, particularly brutal. The authors’ caveats and repeated efforts at alternative definition have been echoed in subsequent scholarship: in the more than five decades since, there have been innumerable further attempts at definition, yet in the words of cinema historian Mark Bould, film noir remains an “elusive phenomenon … always just out of reach”.

Though film noir is often identified with a visual style, unconventional within a Hollywood context, that emphasizes low-key lighting and unbalanced compositions films commonly identified as noir evidence a variety of visual approaches, including ones that fit comfortably within the Hollywood mainstream. Film noir similarly embraces a variety of genres, from the gangster film to the police procedural to the gothic romance to the social problem picture — any example of which from the 1940s and 1950s, now seen as noir’s classical era, was likely to be described as a “melodrama” at the time.

While many critics refer to film noir as a genre itself, others argue that it can be no such thing. While noir is often associated with an urban setting, many classic noirs take place in small towns, suburbia, rural areas, or on the open road; so setting cannot be its genre determinant, as with the Western. Similarly, while the private eye and the femme fatale are character types conventionally identified with noir, the majority of film noirs feature neither; so there is no character basis for genre designation as with the gangster film. Nor does film noir rely on anything as evident as the monstrous or supernatural elements of the horror film, the speculative leaps of the science fiction film, or the song-and-dance routines of themusical.

A more analogous case is that of the screwball comedy, widely accepted by film historians as constituting a “genre”: the screwball is defined not by a fundamental attribute, but by a general disposition and a group of elements, some—but rarely and perhaps never all—of which are found in each of the genre’s films. However, because of the diversity of noir (much greater than that of the screwball comedy), certain scholars in the field, such as film historian Thomas Schatz, treat it as not a genre but a “style”. Alain Silver, the most widely published American critic specialising in film noir studies, refers to film noir as a “cycle” and a “phenomenon”, even as he argues that it has—like certain genres—a consistent set of visual and thematic codes. Other critics treat film noir as a “mood”, characterise it as a “series”, or simply address a chosen set of films they regard as belonging to the noir “canon”. There is no consensus on the matter.