Like so many issues, energy is a debate packed to the gunnels with vested interests, lobby groups and politics. On whom can you rely to be objective and to make the right decisions for the right reasons? Rhetorical questions notwithstanding, it is vital for the country that we solve the issues, invest wisely and have a low-carbon future with plenty of cheap energy to fuel and heat our homes, run our businesses and drive future growth and prosperity.

Sounds easy, doesn’t it? Alas not, primarily because:

- There is no silver bullet – no one solution will provide all the answers, so it’s about a portfolio of energy sources

- Whichever way it is done, there is a cost – financially or otherwise

- There are losers as well as winners with any choice of energy solution

- There are also risks attached.

As a nation built on coal, our energy policy was traditionally in coal-fired power stations, supported by the discovery of North Sea oil and natural gas. Our efficiently extracted oil and gas reserves are now drying up, and the cost of importing will be considerably higher – particularly since the alternatives to oil usage (eg. electric cars) are still in their relative infancy. Global oil production and control of production has been an issue in my lifetime with OPEC countries causing panic in the 1973 by placing an embargo on oil exports.

Wikipedia lists our energy sources in 2011 thus:

- Natural gas: 41%

- Coal: 29%

- Nuclear: 18%

- Renewables: 9%

- Other: 2%.

While our 2005 usage of energy was as follows:

- Transport: 35%

- Space heating: 26%

- Industrial: 10%

- Water heating: 8%

- Lighting/small electrics: 6%

But things must change. One driver is the global debate on climate change, though many in the pro-oil lobby are still in total denial of this, much as the tobacco lobby denied for decades that smoking causes cancer, although they knew it only too well behind the scenes. CO2 emissions (“greenhouse gases”) have a know environmental impact, yet in our current world they are the cheapest to produce to fuel economic activity. According to the evidence amassed on the carbon footprint site, if we do nothing to lower our carbon footprint globally, the consequences will be catastrophic:

The evidence for global warming and climate change includes the following:-

- Sea temperatures have risen by on average 0.5 degrees C (0.9 degree F) over the last 40 years [Tim Barnett, Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California]

- 20,000 square kilometers of fresh water ice melted in the Arctic between 1965 and 1995 [Ruth Curry, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Connecticut]

- Worldwide measurements from tidal gauges indicate that global mean sea level has risen between 10 and 25 cm (18 cm average) during the last 100 years [Warrick et al., 1996]

- Global surface temperatures have risen about 0.7°C in the past 100 years [Met Office]

- 11 of the last 12 years rank amongst the 12 warmest years on record for global temperatures (since 1850) [IPCC, 2007]

- Since 1975, the increase of the 5-year mean temperature is about 0.5°C – a rate that is faster than for any previous period of equal length [NASA, 1999]

- Average annual temperature in the Arctic has increased by about 1° C over the last century — a rate that is approximately double that of global average temperatures [IPCC, 1998]

- There is widespread evidence that glaciers are retreating in many mountain areas of the world. For example, since 1850 the glaciers of the European Alps have lost about 30 to 40% of their surface area and about half of their volume [Haeberli and Beniston, 1998]

- Climate model simulations predict an increase in average surface air temperature of about 2.5°C by the year 2100 (Kattenberg et al., 1996).

What will happen in the future if we do nothing?

- The likelihood of “killer” heat waves during the warm season will increase (Karl et al., 1997)

- The IPCC Second Assessment Report estimates that sea-levels will rise by approximately 49 cm over the next 100 years, with a range of uncertainty of 20-86 cm.

- Sea-level rise will lead to increased coastal flooding through direct inundation and an increase in the base for storm surges, allowing flooding of larger areas and higher elevations.

- Further melting of the Arctic Ice Caps (at the current rate) could be sufficient to turn off the ocean currents that drive the Gulf Stream, which keeps Britain up to 6°C warmer than it would otherwise be.

The trouble is that to do anything successfully requires all nations to co-operate and collaborate, hit targets and not cheat for their own personal gain. The worst offenders are the tiger economies, low-wage fast-growing countries that frequently ignore the rules and emit at the fastest rates. The US attitude and policy has not helped, being negative to joining forces to reduce emissions, partly because of the desire to keep the American economy dominant, and also apparently because the highly religious nation has a fatalistic view about the end of the world, but international jealousy and politics have dominated a debate seen by scientists in pure terms that we need to co-operate in order to survive.

Against this backdrop, and the targets set for every nation to cut CO2 emissions (including China), the UK energy debate has been hijacked in every direction, not helped by the fact that making the right long-term decisions is not a vote-winner in politics, and politicians are invariably short-termist by nature – they care only about being re-elected.

A prime example of this came up last week, with our government giving NIMBY residents the right to block wind farms in their vicinity, and also to gain from lower electricity bills resulting from the sale of power back to the National Grid. Sounds good? Well, bear in mind that the beneficiaries are mostly in the Tory shires, therefore this is primarily a sop to Tory voters, quite apart from the mixed messages it gives about renewable energy sources from the self-declared “greenest government ever.”

I don’t say that in a divisive way, since all governments are as bad as one another, but it does indicate clearly that decisions are not necessarily made with the purest of intentions – and the fact that successive governments have dithered over the siting nuclear power stations and permanent nuclear waste disposal sites is not accidental either.

So what options do we have? The Energy Bill 2012/13 (see the full text at the bottom of this blog) is the latest in a long line of energy legislation. It aims to close a number of coal and older nuclear power stations to cut emissions by 50%, but does not provide definitive framework to manage production and sourcing. Rather, it furthers previous legislation on the “competitiveness” of energy markets and the energy efficiency of our economy. For example, in 2009 the UK Low Carbon Transition Plan aimed to ensure that:

- Over 1.2 million people will be employed in green jobs.

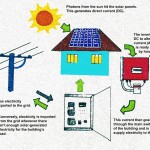

- The efficiency of 7 million homes will have been upgraded, with over 1.5 million of them generating renewable energy.

- 40% of electricity will be generated from low carbon sources (renewables, nuclear power and clean coal).

- Gas imports will be 50% lower than would otherwise have been the case.

- The average new car will emit 40% less carbon compared to 2009 levels.

Whether cars and new homes are but a fraction more energy efficient is not clear, but I would bet that techniques which deliver mass market benefits from techniques that up to now have been reserved for the wealthy few have not found their way into the mainstream. The key decisions are therefore not limited to what sources we shall use but also how they should be funded. And from a government perspective it should be a reluctant private sector taking the lead. To encourage investment, governments therefore turn a blind eye to profiteering by the cartel of energy companies and instead promote the alleged benefits for consumers of switching. I for one am far from convinced, not least because of the impact on fuel poverty – also a government responsibility (Wikipedia):

Reducing occurrence of fuel poverty (defined as households paying over ten percent of income for heating costs) is one of the four basic goals of UK energy policy. In the prior decade substantial progress has been made on this goal, but primarily due to government subsidies to the poor rather than through fundamental change of home design or improved energy pricing. The following national programs have been specifically instrumental in such progress: Winter Fuel Payment, Child Tax Credit and Pension Credit. Some benefits have resulted from the Warm Front Scheme in England, the Central Heating Programme in Scotland and the Home Energy Efficiency Scheme in Wales. These latter programs provide economic incentives for physical improvement in insulation etc.

One of the alternatives are “clean coal” power stations, for which ready sources are still viable in the UK. However, this does not appear to be a major league solution. Support within government has been grudging, possibly because more ministers appear sold on nuclear power than any other source. Nuclear, they would argue, has come a long way since the failures of older designs and disasters like the meltdowns at Three Mile Island and Chernobyl and other nuclear catastrophes, though Fukishima in Japan in 2011 demonstrated that unforeseen eventualities can occur at any installation at any time. Small wonder nuclear energy and the threat of radioactive pollution has failed to convince the population of its safety record.

More than that, nuclear energy requires a vast up-front investment to build new generation fast breeder power plants, which have a finite life span but can utilise the earth’s endless reserves of Uranium-238. No doubt they could, while operational, deliver a considerable proportion of the national grid’s continuous electricity, but they also leave nuclear waste to be reprocessed and stored for its half-life – estimated at 1.41×1017 seconds (4.468×109 years, or 4.468 billion years.) Decide you want to be rid of nuclear power stations and the decommissioning process takes years!

It might be an easier decision for a politician, since they won’t be around to reap the consequences if something does go wrong, but by the time you weight up all the cons to nuclear plants, you wonder how many alternative energy sources you could have brought on stream, the sort that don’t have any of the downsides of nuclear power. The benefit is that these forms of energy use safe and replenished resources of the earth – all sustainable and available to be harnessed according to the geographical properties of your area; the problem, air turbines as an eyesore notwithstanding, is that they are not constant and would need back-up sources for times when the sun does not shine, the wind doesn’t blow etc.

There are plenty of renewable options though, including but not necessarily restricted to:

- Biomass

- Biofuel

- Hydropower

- Windpower

- Solar energy

- Geothermal energy

- Oceanogenic energy

Whether we take advantage of any combination of these options, individually or nationally, using the “big six” energy providers to do it for us, it is more a matter of our national will and determination to act than the handicaps of any given source. Fact of the matter is that we are probably confused by the debate and don’t care about the sources so long as we get cheap energy and fuel for our cars – which for the most part still use essentially the same internal combustion engine they did over a century ago. We are much more concerned about the rise of energy prices in the short-term, and therefore allow our politicians to get away with fudging the long-term debate. While this continues, no progress will be made.

Some years ago during my MBA course a colleague and I did some interviews of various people in the energy industry for a group presentation given by our syndicate. One such as a chap who worked for BP but was responsible for research into alternative renewable energy sources. This, we suggested, was small beer for BP. He cheerfully acknowledged that it would take 20 years plus for the company to regard his division as being in any way significant as a generator of revenues, and while oil lasted that would be the mainstay of energy supplies.

BP along with the other major oil and energy companies, car and aeroplane manufacturers and many more key players could drive a revolution in energy supply and drive a huge change in buying patterns, if they had the mind to do so. But then if fossil fuels cost less and are easier to flog, what incentive do they have to change? Government has to offer the tax breaks first, it would seem.

But then, governments also seem reluctant to do more than offer the occasional grant to allow people to offer renewable sources, and now they are withdrawing the incentives to open wind farms. Certainly no major kick up the backside for the energy providers to change, despite the fact that we will miss our CO2 targets. In fact, our emissions are rising!

However, such is the hot potato and so bitter the arguments between different lobby groups, the government seems mesmerised and incapable of radical and affirmative action to move this debate on with a major step change. Perhaps we should not be surprised, but this demonstrates precisely why some policies are too important to be entrusted with politicians.

Give me someone who can take a measured decision on our energy portfolio and make the best decision from the facts, regardless of profiteers and NIMBYs, and not wimp out by electioneering as the party flogging energy at the lowest tariffs. If this is a debate we need one that embraces everyone and gains consensus for the right reasons.

PS. As a closing shot, this discussion of UK energy policy is worth repeating in full. With thanks to Politics.co.uk:

What is energy policy?

An enormous headache for Britain’s policymakers, that’s what. ‘Keeping the lights on’ might seem like a flippant cliché to some, but it is a serious business for those tasked with making sure there is enough electricity to go round over the next century or so. The struggle between different sources of energy is being fought on a complex battlefield of relative merits which will eventually determine our ‘energy mix’. At the same time, policymakers have to balance the needs of the companies providing energy with the consumers who need it. Both have to be encouraged to make efficiencies wherever possible, and both have to be talked down from bitter confrontations with the other. Then, over all this policy turmoil, comes the biggest headache of all: the thunderhead of the climate change threat, weighing down on the sector and placing intense pressure on ministers to decisively shift the ways in which we generate our electricity.

Background

The biggest target of all is enshrined in law under the Climate Change Act. By 2050, Britain’s total emissions have to fall by 80% on their levels in 1990. There has been some progress on this; between 1990 and 2010 UK emissions were cut by 20%. That’s faster progress than the EU, which as a whole only managed a cut of just over 15% during the same period. We shouldn’t be patting ourselves on the back too much, though. Much of the legwork has yet to be done, with a 50% cut supposed to be achieved as soon as 2027. The clock is ticking.

How to get there? Many believe the answer is replacing old, carbon-heavy energy sources like oil- and coal-fired power stations with renewable energy. About 20% of our current power-generating capacity will be shutting up shop in the next ten years or so. In part this is because of an EU directive of 2001 which forced the closure of large combustion plants which couldn’t cope with new emission standards. Two-and-a-half cities’ worth of power will have shut down by 2015.

This shouldn’t be a problem because the government is legally committed to meeting 15% of the UK’s energy demand from renewable sources by 2020. The Department for Energy and Climate Change (Decc) is attempting to achieve this via a raft of measures. Feed-in tariffs have subsidised the development of small-scale low-carbon electricity generation. A renewable heat incentive offers payback over a 20-year period for commercial, industrial, public and other generators of renewable heat. Companies supplying over 450,000 litres of fuel per year are obliged to source a percentage from a renewable source. It is a mixture of stick and carrot which is costing consumers about £2 billion a year. This will have to rise to nearer £8 billion to meet the directives target, thinktank Civitas has warned.

This is the context for the energy bill, which was introduced in the 2012/3 session and was one of four bills to be carried over into the coalition’s penultimate session. The aim is for the legislation to pave the way for £110 billion of investment – a substantial amount, but not enough according to some.

The oil and gas industry is not standing back and letting the shift to renewables overwhelm it. It is an “expanding industry”, business secretary Vince Cable said in April 2013, which provides nearly £27 billion of revenue in alone and has an extensive supply chain viewed as a strategic resource by those in power. Big oil still matters: the industry supports 440,000 jobs across Britain and currently meets half the country’s main electricity needs. The Treasury appreciates its contribution, too; in 2012 the sector paid £11.5 billion into the chancellor’s coffers. The government launched its oil and gas strategy in 2013, in which it pledged to continue working with the industry as it provides energy “for many decades to come”.

It is over those decades, though, that the big transition to renewable will also take place. Ministers could very easily meet the climate change targets if they wanted to – anything is possible at a price. That is the problem. Consumers are already seething with anger at the high cost of their energy bills. Attempts to plaintively explain that government policies can only influence around 11% of their bill are usually met with deaf ears. Global oil and gas prices are the biggest drivers, ministers insist. That is true, but it does not stop voters from being deeply suspicious of slow-moving energy firms shifting their prices downwards when global prices fall.

Decc has attempted to combat scaremongering about energy bills by producing its own figures. Its estimated average impact of policy tweaks on household energy bills calculates a total cost of £286 a year, but also savings of £452 – ie: bills will be lower by £166.

The debate is also a little misleadingly focused on electricity and power, which only accounts for one-third of the UK’s energy needs. Transport, dominated by oil, accounts for another third, while heating (dominated by gas) makes up the final third.

Politics plays a big part in this debate. The Conservatives are naturally suspicious of some sorts of renewable energy – just look at former energy minister John Hayes’ brazen opposition to wind energy, for example. While energy and climate change secretary Ed Miliband eschewed nuclear energy, which had been preferred by New Labour, in favour of what critics claimed was ‘grandstanding’ on climate change.

Bubbling away under the surface of this debate is a clash of ideas and attitudes which often finds itself reflecting the bigger partisan divide in this country’s politics. Conservative big beasts like Lord Lawson are firm climate change sceptics; others simply believe Britain, which only contributes two per cent of global climate change emissions, is doing too much.

Can shale gas be developed commercially? Its possibilities remain substantial, but there remain lots of question-marks about its viability too.

There is a third factor in the equation though, completing the triangle in what the Energy Technologies Institute describes as an ‘energy policy trilemma’. In addition to making energy sustainable and affordable, it also has to be secure.

Controversies

The attempt to replace emissions-heavy energy production with renewable alternatives is undermined, in the views of some, by the nagging suspicion that the switch is simply not plausible. Transferring from a fossil-fuel-dominated energy mix to one powered by renewable and nuclear energy involves serious engineering, financial and economic challenges which could prove impossible to achieve if consumer bills are to be kept in check, warns Liberum Capital. Its assessment – that utilities companies and investors should steer clear for the time being “as the implausibility and contradictory nature of policy is exposed by events”.

Gulp. This view is not an isolated one. The fear of a “pinch point” is being articulated by Energy UK, the industry body’s main organisation, which fears an energy gap is opening up. “Are energy prices going up and will they going to continue to go up? Yes,” says its new chief Angela Knight, herself a former minister under the Major government. “Why? Because we are dependent on the world price of gas, which is increasing, and we are shutting down our coal-fired power stations. Coal produces 40% of our electricity and it’s cheap. But we’ve got an emissions directive that is going to shut down a quarter of our coal-fired powers stations before 2020.”

The civil war between the renewable energy sources also generates intense controversy, as each option on the menu points out what’s wrong with all the others. Onshore wind energy is bashed by anxious backbenchers keen to protect their local landscapes, which is why in Britain the emphasis is usually on offshore options. Costs are relatively low and are set to decrease, but rely on government subsidies nonetheless. Tidal, geothermal and biomass energy are all variously dismissed for being too expensive, or too unreliable, or too energy intensive to produce.

Then there’s the nuclear option. Energy giant Centrica raised eyebrows in February 2013 by abandoning its 20% stake in the Hinkley Point project being headed by French company EDF Energy. The plan to build two nuclear reactors will cost £14 billion, but with one big firm voting with its feet its prospects are now looking uncertain. Nuclear is an economical and clean source of energy – provided industry disasters like Fukushima and links to serious diseases are ignored. It is able to scale-up in a way that most renewable sources are not; whole cities can be powered by nuclear power plants, whereas wind energy is often more localised. Ultimately, the stakes are higher. Construction takes longer. High subsidies and loan guarantees are often essential. Then there’s the small question of nuclear waste, which lasts for an appalling 500,000 years.

Whichever option the government goes for, opponents of the push to tackle climate change will be critical of the price being paid by energy consumers. This means business as well as households: the independent Committee on Climate Change estimates climate policies already in place have together added 21% to Britain’s industrial electricity prices. This would be less painful for those against the government’s approach if they didn’t feel the reliance on subsidies was making the transition even more powerful than it has to be. It’s feared the reliance on subsidies is holding back companies from innovating the conversion devices to make renewable energy sustainable in the long-term.

Decc faces criticisms over its attempts to tackle another big part of the energy debate – limiting the demand for energy in the first place. Its Green Deal aims to help households and businesses to increase their energy efficiency. This is a laudable part of its bid to fulfil Cameron’s pledge to be “the greenest government ever”, a promise seized upon by environmental campaigners as the standard by which the coalition can disappoint as nauseam. On the Green Deal, though, there does seem to be room for disappointment. Three years into the coalition, the energy and climate change committee was forced to conclude in a recent report that ministers still couldn’t really define what they wanted to achieve with the programme.

A firmer shift being pushed through by the coalition is the plan to make consumers’ task easier in switching between energy firms. The myriad of pricing options currently on the market is to be simplified, forcing consumers on to the cheapest tariff available. Experts have warned some customers on the cheapest of the deals available at present could end up paying more as a result of the changes.

By mid-2013 a fresh challenge was emerging: allegations of petrol price-fixing which could have meant motorists paying far more at the pump than they need have done. The scandal, which was being investigated as this article went to publication, suggested major players in the industry could have questions to answer about potentially criminal activity, placing further pressure on ministers to come up with a robust response.

Statistics

1,611,000 barrels of oil: The amount of oil consumed by Britain in 2009. That number is comparable to Iran (1,741,000), less than China (8,625,000) and significantly less than the US (18,686,000) (source: BP statistical review of world energy)

2012 electricty generation share: Coal 39.5%, gas 27.5%, renewable 11.5% (source: Department for Energy and Climate Change)

24 billion barrels – the upper estimate of oil reserves still remaining in the North Sea. The number could be as low as 15 billion barrels, however. (Source: Oil and Gas UK)

Quotes

“It is the duty of the Secretary of State to ensure that the net UK carbon account for the year 2050 is at least 80% lower than the 1990 baseline.

(2)’The 1990 baseline’ means the aggregate amount of—

(a)net UK emissions of carbon dioxide for that year, and

(b)net UK emissions of each of the other targeted greenhouse gases for the year that is the base year for that gas.” – the Climate Change Act 2008 clause legislating to cut carbon emissions by 2050“Global gas price hikes are squeezing households. They are beyond any government’s control and, by all serious predictions, are likely to continue rising. We are doing all we can to offset these global energy price rises, and while we have more to do… our policies are putting a cushion between global prices and the bills we all pay.” – energy and climate change secretary Ed Davey, March 27th 2013

“Rising energy prices are consistently one of consumers top financial concerns and millions will be shocked by the size of their bill after such a cold winter. Bills will only be kept as low as possible if there is more effective competition, easier switching between suppliers and every tariff presented in a clear, consistent and simple way so people can easily spot the cheapest deal.” – Which? executive director Richard Lloyd, May 22nd 2013