There’s something about the railways that brings a tear of nostalgic joy to many an eye. The tendency is to hark back to “the golden age” and bemoan the current situation, though ’twas ever thus – our memories associated with rail transport belie the reality that the industry has always been fraught. If there was a golden age it was probably in the pioneering years as this country forged the first steam railway network in the world.

I don’t propose to go over the history of railways, only insofar as it is relevant during my own lifetime. When I was young the railways were nationalised under the factual but unimaginative title of British Railways. BR, as it was always known, was loved and hated in equal measure, but remembered under the stylised logo depicting tracks in two directions, the strapline “This is the age of the train” and the now disgraced Jimmy Savile appearing on ads to persuade us to make greater use of the services.

BR did a moderately competent job of running and modernising the system within the tight boundaries imposed by the Treasury and subsidised fares that made it affordable to use. In fact, the impact was to starve BR of investment by successive governments for one reason only: to spend the millions needed to effect a complete modernisation of the system.

The issue of investment was shamefully ignored by successive governments from the point where the failing private companies were renationalised, through the infamous Beeching report, which closed down many minor and unprofitable lines for good, and right through the 60s and 70s. It was one of a number of elephants in the room down at the House of Commons – enough for a performing troupe, you might say.

In this case, the fact of the matter was simple: spending many millions on rail would not win votes, particularly if the opportunity cost was to reduce spending on areas that would win votes. Every decision has always been taken piecemeal, based often on the effectiveness of those lobbying government rather than the actual needs of people and business. The road lobby won the debate on road building in the 70s and 80s, but then road users are taxed heavily and are a source of revenue to government, where rail is merely a cost.

Small wonder that it missed out, in spite of the eternal need for sustainable low-carbon non-polluting mass transit systems going to the heart of cities and out into the provinces and the countryside, where residents have often had no obvious travel choices post-Beeching but for car and bus. Living in Tiptree, I still need my car to get to the train station, if I choose to go to London for business or pleasure. But the need for a first class rail system has always been undeniable, the only question being how it should be refurbished and maintained as an efficient and speedy form of transport that adds value to the economy.

The privatisation of the rail was to some on the left a complete anathema, though most observers would agree that something had to change to introduce fresh capital and revolutionise the industry that had fallen well behind the standards set by other countries – France and Japan being the two that invested strongly with high-speed rail lines at affordable prices, subsidised but not entirely funded by the public purse.

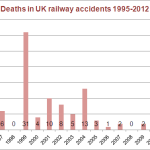

That gripe aside, there were two main problems in the UK, one being that we had fallen so far behind the standard of track and signalling was positively antique (quite apart from many delays caused through maintenance and signal failures, both resulted in accidents and fatalities at regular intervals); neither had the latest safety equipment been deployed to prevent accidents, since it failed the cost:benefit test (saved lives do not apparently justify the money spent, which shows what our government really thinks of us!) Large portions of the UK rail network were not electrified, the rolling stock was positively ancient, and none of the network was compatible with the latest generations of high-speed trains. Small wonder comparative reports consistently judge our railways among the worst for fares and efficiency.

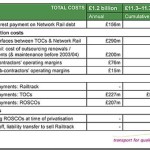

So finding ways to establish a partnership with the private sector was not really the problem. The main problem was in how it was achieved, in the chaotic way the fares structure was put about, in the short-term franchises, in the subsidy system that was supposed to taper down to zero but continues to this day, even if that meant the passenger, notably the commuter who has no choice but to use the rail system to get to central business areas, was squeezed til the pips squeaked.

It was supposed to introduce competition, but I defy anyone to identify that competition between providers has forced prices to stay down. If anything, the fare structure is far more complex, and information harder to uncover, though consumer groups have thankfully begun compiling some of the many quirks in the system that allow you to pay less. Some are obvious – yield management systems like the railways mean that purchasing your ticket in advance via special saver fares give you access to the best available headline rates for travel, where short notice means exorbitant standard fares. Others are quirky and illogical, such as travelling via obscure routes, buying tickets to intermediate destinations and many more strange inconsistencies. Would it not be more logical to have a system where ALL rates were clearly obvious and easy for anyone to get the cheapest fare available?

In short, privatisation was done as a short-term expediency, based on ensuring something was in place during the life of a parliament, but lacking a consistent long-term strategy for success based on hard evidence, and was clearly not set out with a clear vision of what we expect from a rail system and what resources we are prepared to put in to make it justifiable. If it had been, things could have turned out very different, but no government has really grasped the issue of correcting the fundamental flaws.

For example, train operating companies have come in for much criticism. In the early days their drive for making franchises was self-evident, as they sacked drivers but then had to re-employ them on a freelance basis when it became obvious they could not meet their contractual responsibilities. Targets gave them distorted incentives to keep trains to timetables, sometimes by failing to stop at particular stations, reducing the number of carriages so fare-paying passengers were treated like cattle en route to slaughter. No, scrub that – animals actually get treated better, courtesy of the law. Apparently it’s OK for us to endure any temperature and be packed like sardines AND pay through the nose for the privilege (you can’t reserve a seat on a commuter train!) One way or another we pay through the nose every time.

Some operators have effectively resigned from franchises because they couldn’t make money, while others have been sacked for failing to meet the standards of service expected. But for the paying public the frustrations have remained – the operators make huge profits for their shareholders, pay big bonuses to execs, while charging the customer through the nose and continuing to provide shoddy, unreliable and uncomfortable trains.

Some things have improved – franchises are now longer to help operators make long term returns on investment. Promises have been about service improvements, frequency of trains, number of carriages etc. and sometimes they have been delivered too.

For my part, I’ve often had no choice but to travel by train, since the rail alternative to the places I was going have tended to be obscure and costly. But having spent years commuting and travelling around the country by rail, I’d say it was always the best option – providing you can get a seat and the nightmare scenario can be avoided whereby few trains are running and passengers are practically fighting to get on the ones that do. It was awful being on the concourse at Liverpool Street waiting with thousands of others for the board to change, a platform number to appear, then rushing with sharpened elbows to get in there to fight for a seat before it was too late! Still, if you got there in time, you could read a book, play on your mobile or even snooze, none of which are a good idea while you’re driving!

Are we any further on in 2013? Well some positive decisions have been taken to improve the network. Tram systems run by local authorities in cities have combined old rail routes and tracks around city centres – not cheap but a big advance in city commuting. The Channel Tunnel and the high-speed rail lines into St Pancras, plus the complete regeneration of St Pancras and Kings Cross, were a very positive move. The Crossrail system was kicked about like a political football for many long years, but finally it is being built.

And now we have HS1 and HS2 – high-speed rail routes to speed journeys through to the main rail hubs around the UK, though the counter-argument is that the benefit is relatively small and for few, the destruction of wildlife habitats permanent – but then that is a stumbling block to any improvements in national infrastructure – and the cost, notably at a time of austerity, is exorbitant. If you took the cost argument, and governments did pussyfoot around these issues for many a long year, the existing rail system would continue to be patched up and no further advance would ever be made. If there was an alternative that did give us a system fit for purpose over the next 100+ years cheaper, no doubt that would have been chosen – and we the taxpayer and passengers will continue to foot the bill with huge fare increases above the rate of inflation.

Evidently it came to a final moment when the decision could not be put off any longer and we have to bite the bullet: do we want a decent rail system for the future or do we not? But the fact is that unless the economics are right, people will shy away from rail travel. Despite huge increases in the cost of motoring, we still take our cars as first choice thanks to inelastic demand: it is far and away the easiest and most convenient way for us to get around.

So much for sticks, when are we going to get some carrots to make it easier and cheaper for us to travel by efficient means of travel that do not create vast polluting carbon emissions, are generally far safer and less stressful, and get us to our destinations quicker and without congestion?