Ever noticed how the most beautiful and perfectly sculpted things in life, be they works of art, buildings, processes, ideas, anything, are all incredibly simple at heart? They leap through boundaries, make you say to yourself: “Why didn’t I think of that?”

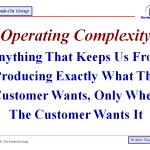

Every working day I watch how the duties of NHS trusts are shrouded in endless layers of complexity, how staff can’t see the wood for the trees, and how difficult it is to accomplish even simple changes. There are many reasons for this, but it doesn’t have to be that fiendish – if you can wean people off the complex ways and workarounds that have grown up over time.

The NHS is a prime example of that. Once you have a clear understanding of the ins and outs of the healthcare economy, it’s not especially difficult to see what is wrong and what needs to change, but how you overcome inertia and stop doing the complex things that cause so much unnecessary manual effort can be blindingly complicated. It’s not that people don’t want to do it, they can’t see ways to stop in order to start doing things differently and identify which path will actually result in a simpler life – doing the same things is so habitual you can’t imagine anything different. This is the hamster wheel of the modern working environment. You do it because you have to do it, and while you might dream of a simpler life you somehow never quite get there. Or do you?

As time passes, and everything becomes progressively more complex and time consuming to make in order to make our lives simpler, occasional step-changes towards a new technology reverting back to the essence of simplicity. Labour saving gadgets become household necessities. Herein lies the essential paradox of modern living.

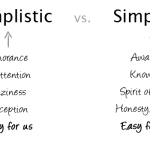

Years ago I bought Edward de Bono’s excellent book Simplicity, in which he points out that some people delight in complexity and hate simplicity, in part because that way they can hide behind the systemic workings and also demonstrate their own value: if things were simple and easy, would I have a job here? Redundancy is the fear, especially in austere times, but equally it could be an opportunity you never previously had.

Set a beacon for how simplicity and automation benefits staff by freeing them to do the jobs they should be doing and which add greater value, rather than being enmeshed in endless iterative levels of detail created by complexity – but then, do they want to have their chains snapped and to be offered greater freedom?

Simplicity in essence requires a different mind set, for which de Bono drew up the ten rules of simplicity:

- You need to put a very high value on simplicity

- You must be determined to seek simplicity

- You need to understand the matter very well

- You need to design alternatives and possibilities

- You need to challenge and discard existing elements

- You need to be prepared to start over again

- You need to use concepts

- You may need to break things down into smaller units

- You need to be prepared to trade off other values against simplicity

- You need to know for whose sake the simplicity is being designed.

Of course, discarding things an organisation has done for generations, and in many cases for which there are national standards about how they will behave, could prove impossibly difficult.

So maybe there should be an 11th rule added to the list:

11. Select the elements most in need of simplification and use those as a blueprint for others to follow.

Paradoxically, simplicity is very difficult to visualise unless and until you see it in action. On paper it looks wonderful, but as soon as that is proposed for reality there is much opposition and resistance. “What if…” they will say. It’s not difficult for reasons not to do something new and different, but then the thing about complexity is that it sweeps along all before it, so you can’t see any way around but to be wound up in its tendrils and talk about the detailed minutiae rather than seeing the glaring faults in the system as a whole. Strangely, this is as true of people in very senior positions, the ones who should be strategists, seeing the big picture and setting plans and policies for a brighter new future.

So there are two approaches to complexity: one is to start again from scratch and design from the ground up to be simple – and that works if you employ Business Process Re-engineering to achieve the same business outcomes quicker, simpler and more efficiently, for example – or to embrace it and find ways of dealing with it.

The Internet might have brought us a whole new world of complexity and shades of opinion, plus the anarchic loss of control over how the system develops, being the product of endless million human brains, but it also gives us the opportunity to find better ways to filter information so we can find only that which adds value for our purposes. Search engines are one way, and you can be quite sophisticated in how you use them. The point is to spot trends and patterns in the flow of information and to identify their relevance. If you get caught up in the detail you will never change your system based on the best and most inventive of ideas, or more to the point harness the best of thinking elsewhere quickly and easily.

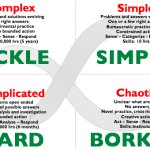

You can of course use modelling solutions to develop a framework for managing complexity, of which this is a nice example of a decision-support framework against which to measure current scenarios. The benefit of this kind of approach is the ability to project forwards and demonstrate that if I do this, that will be the impact, whereas if I change to another approach I can achieve those targets with these resources at that cost.

It seems odd that we are forever offered improved convenience, but when it comes to ourselves and how we manage our working lives, we would often be suspicious of anything that simplifies life and leaves us free to think and innovate and be creative. To me, creativity is the great goal – just wish other people saw the creative in themselves.