I’ve written before about transport policy and how successive governments have screwed it up through lack of investment, lack of joined-up thinking, being motivated by political and electoral prejudices, ignoring cost/benefit projections from their own department, choosing the wrong projects for the wrong reasons, often informed by the next election rather than a strategic horizon. This works both ways – some vanity projects go ahead while more sensible ones which offer a clear benefit are delayed eternally, if ever they go ahead.

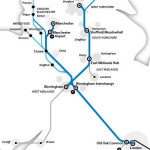

There are frequent reminders of the skewed decision making processes, of which one is the decision to go ahead HS2 line from Euston, which we could have developed more cost effectively had a decision been made years previously, along the lines taken in France, Japan and elsewhere. Costs are rising, benefits falling, but still the programme continues – ignoring justifiable protests as it goes along its merry way.

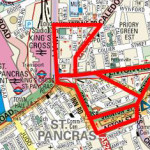

But the worst of it is that the politicians who took fairly arbitrary decisions on HS2 gave no forethought to linking the service up to the Eurostar service, which for political reasons was terminated at St Pancras. Euston and St Pancras are relatively close but for any visitor to the UK the impression given is of a disjointed approach with no continuity to link in the whole country to Europe. A good strategy would have taken this into account long, long before decisions were taken. As it is, the only beneficiaries will be taxi drivers going from one station to the other.

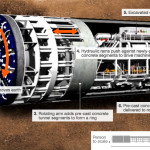

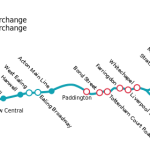

However, this blog is about London transport policy. There is one major capital project under way in London, one delayed repeatedly through lack of political will, but finally going through. That is Crossrail, a high speed rail line from east to west and west to east, mirroring the Thameslink service from north to south. Crossrail has been a hot potato for many years, despite a very clear benefits case, though at long, long let it is now being built.

But my main focus is not the big capital expansion projects, important though they may be. It’s the illogical nature of day-to-day transport management within our capital, a city where people have no choice but to commute from the suburbs into and out of London. While many curse the tubes and buses, they are in many ways the 8th wonder of the world. Tubes are the more accessible of the two, providing you take careful note of your route and the destination of the train in question; buses are amazing but very difficult to fathom unless you are initiated by somebody who already knows their way around.

I remember commuting to a clinic in deepest darkest Lambeth for several months. It took me most of that time to work out which buses formed the most efficient route to get me closest to my destination, but once I had sorted it I could sit back and enjoy London from the romantic heights of the upper deck. You can get a bus anywhere if you know which one to get, and the journeys are often a remarkable voyage of discovery into deepest darkest London, the parts that visitors never normally reach. Just take time and keep your eyes peeled, and if you have time to spare get a day travel card, hop on a bus at random and see where it takes you!

All well and good? Not quite. The logic of some aspects of the management of London travel always seemed to me odd, to put it mildly. One relates to the fact that there are no fewer than 6 fare zones around the city, some barely covering a single station. Granted some outlying suburban stations are considerably further away than depicted by our infamous stylised tube map, but six zones seems to me overkill and typical of the convoluted thinking that clouds transport policy. It is that fastidious mindset that suggests that while some innovations are worthwhile (eg. Oyster cards), the people responsible for London transport (ultimately the mayor’s office) have only a vague idea what it is like to have to get around town and where the system is heading. The communication is often less than clear.

Extend that to another scenario: you may be aware there was last week a 2-day strike on London Underground, prompted by the RMT, of whom Bob Crow was the infamous head before his sad and untimely demise. Now Mr Crow was a divisive character who evoked strong emotions on either side, whose reputation for tough negotiation on the part of his members won him friends and excellent terms and conditions for his members, but whose radicalism and apparent tough-as-nails intransigence made him enemies aplenty, often quoted by government and right-win media sources as being the human face of “70’s style union madness”, which in the long run may have lost the RMT some public sympathy underground employees might otherwise have earned. The public hate strikes and businesses suffer because many people can’t get to work, and whatever the rights or wrongs of a dispute it’s the innocent passengers who suffer most. The problem is that withdrawal of labour is historically the only tool open to unions if faced with an intransigent management that refuses to consult or negotiate.

As it was described on the various broadcasts I’ve listened to (with interviewees from both sides), the management and negotiators at TfL and London Underground Ltd refused to listen to ideas from the union, nor indeed to negotiate on any point of their plan to close ticket offices (contrary to Boris Johnson‘s pre-election promise.) It may have been an issue of job losses, regardless of whether or not compulsory redundancies were excluded from the equation (there seems disagreement about the wording on this and other points), but intransigence on both side led to the situation where a ballot was called and strikes announced. Disputes like this become a matter of brinkmanship and shows of strength, escalating the actual points of negotiation beyond all reason – and leaving what is best for passengers, staff and efficient administration a long way behind.

I mention this not from any desire to take sides in the dispute (which involved quite a lot of he-said-this-I-said-that catcalling) but for the fact that good strategic management takes a long-term view and agrees with all stakeholders a development plan which gives can win long-term investment and give employees and customers alike an assurance of where the service is heading. As it is, I suspect many of the plans are short-term panic measures in response to government budget cuts, and being a people-centric business job cuts are inevitable – and this threat is driving the more militant response from the RMT: fail to act in the first tranche and further cuts will follow. It doesn’t have to be like that, but neither should central government be meddling in the strategic planning process any more than Jeremy Hunt should be meddling in the management of NHS Trusts.

In short, it’s all very well gaining approval for Crossrail, but the information available on London’s strategy for transport is minimal, to put it mildly – see here. As citizens and users of the service, should we not be entitled to see a comprehensive programme of changes, big and small, when they will occur, how they are being funded and what impact they will have on our lives? How well will it integrate with the buses, bikes and overland services? Will there be sufficient investment to overcome the many handicaps and delays of the current system? Wait and see…