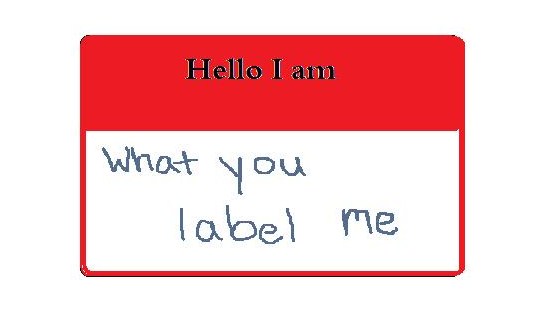

I am a person with diabetes. I am a diabetic.

Above are two statements conveying exactly the same meaning, but they are not the same. The second is a label, an epithet categorising the subject in some way, with positive or negative connotations. Some might regard “diabetic” as a taboo, indicating that I am unclean or undesirable (and that emotion has often been applied to those with HIV, for example, often by those whose labels might include “homophobic“), where others would see it as a common condition, a club with many members. At worst it may be a stereotype based on perception rather than fact.

But then again, that is only one of very many labels that might and are applied to me, some reasonable and others unpleasant. I am white, male, heterosexual, a father, a divorcee, and, depending on how you look at it, an Englishman and/or Brit – though I’d much sooner consider myself a citizen of the world in recognition that all people share a common bond so we should celebrate what unites us rather than what divides us.

I’m also a management consultant, a writer, a homeowner, middle-aged, an actor, a Manchester United fan and an atheist, though politically I might be labelled only loosely as what the Americans call a “liberal” (small L) since I’m known to be equally critical of every label in the political spectrum. I’m not disabled, not a criminal, not an immigrant, which makes me largely conformist to societal norms and not any form of outcast.

Doubtless there are many more which may be applied to me, depending on the context, some of which I would approve and others I would eschew. People who don’t like me may call me a bastard and those who do may say I’m a gent, but both are still labels.

The one I am least fond of is the label given by my parents, namely “Andrew,” so “Andy” is the label I apply to myself. To call a name a label might seem perverse, but your given name (and nicknames) say much about you, your family background, your aspirations, who you see yourself as, what image you want to convey to the world. Small wonder that so many in show business change names that lack the necessary glamour en route to fame. Discarding a name is like shedding a skin, you then become a whole new alter ego.

On the more academic side to this topic, Labelling Theory is defined thus:

Labeling theory is the theory of how the self-identity and behavior of individuals may be determined or influenced by the terms used to describe or classify them. It is associated with the concepts of self-fulfilling prophecy and stereotyping. Labeling theory holds that deviance is not inherent to an act, but instead focuses on the tendency of majorities to negatively label minorities or those seen as deviant from standard cultural norms. The theory was prominent during the 1960s and 1970s, and some modified versions of the theory have developed and are still currently popular. Unwanted descriptors or categorizations – including terms related to deviance, disability or diagnosis of a mental disorder – may be rejected on the basis that they are merely “labels”, often with attempts to adopt a more constructive language in its place. A stigma is defined as a powerfully negative label that changes a person’s self-concept and social identity.

This is the view of the contributor on Wikipedia around this topic:

Labelling or labeling is describing someone or something in a word or short phrase. For example, describing someone who has broken a law as a criminal. Labelling theory is a theory in sociology which ascribes labelling of people to control and identification of deviant behavior.

It has been argued that labelling is necessary for communication. However, the use of the term labelling is often intended to highlight the fact that the label is a description applied from the outside, rather than something intrinsic to the labelled thing. This can be done for several reasons:

- To provoke a discussion about what the best description is

- To reject a particular label

- To reject the whole idea that the labelled thing can be described in a short phrase.

This last usage can be seen as an accusation that such a short description is overly-reductive.

Giving something a label can be seen as positive, but the term label is not usually used in this case. For example, giving a name to a common identity is seen as essential in identity politics. Labelling is often equivalent to pigeonholing or the use of stereotypes and can suffer from the same problems as these activities.

The labelling of people can be related to a reference group. For example, the labels black and white are related to black people and white people; the labels young and old are related to young people and old people.

The one strangely missing from that list is job titles, whereby the labels are also a matter of status, how we see ourselves, how others see us, and how we relate to others around us. People are often more competitive about their job titles than any other aspect of their lives, such that every last nuance of importance can be extracted from the label applied, and from the perspective of employers it was cheaper to give people highfaluting titles than salary rises, thus appealing to a more advance need for self-fulfilment in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Trouble is, many bear no relation whatever to what people actually do, though when they are descriptive they can be a hoot. Some job titles are euphemisms of the highest degree. Examples of all are listed here, here and here – enjoy!

Some titles are long-serving but just as obscure, such as my recent discussion about Deputy Commissioners, Assistant Commissioners, Deputy Assistant Commissioners in the Met Police force (see here.)

In my lifetime it began when people in middle-ranking jobs coveted and were awarded the title of “manager,” even when their jobs did not require them to line manage anyone. It was a default way of saying that you had arrived and were someone of importance in the organisation, though it also works in reverse. Someone I know found their job degraded from “manager” to “officer” in spite of the fact that they did manage a team, though officially they are now regarded as a “supervisor” of the resources in question, despite the actual duties not having changed. Why? Clearly the organisation sees removal of the mantle of management as a way of communicating that they would be quite content if the person concerned resigned and left in order to save costs.

In American corporations from the early 80s on, the explosion came in “Vice President syndrome” – to the extent that there were an unfeasibly large number of people in senior positions, thus degrading the name and requiring new titles to sum up the importance of the people concerned to the organisation.

Another interesting title is that of “Professor“, which means different things according to location and culture. In this country, to reach full professorship is to reach the very pinnacle of the academic profession, something achieved by many years of teaching, research and publication of eminent papers and books in one’s particular discipline. In some institutions it seems to be the norm that if you are a senior lecturer in a department, you become a professor, and fictionally too since every teacher at Hogwarts in the Harry Potter series seems to be called “Professor.”

Jobs apart, we acquire or impart on ourselves labels at all times of life, at least in part because society is not comfortable with people who elude categorisation or, to use the common colloquial phrase, “pigeon-holing,” some means of confirming your conformity by virtue of identifying you with the crowd – assuming you share characteristics rather than recognising the unique qualities that differentiate you.

If you are truly an original, an innovator who ploughs his or her own furrow, you might well create your own categories, but if you evade all comparisons you may well find yourself a total outcast if people don’t have an obvious label through which to relate to you. That distinction falls to relatively few, since so many labels fall into our laps, and maybe we spend a great deal of our time and effort distancing ourselves from how we are seen. The purpose of “celeb culture” in all its forms might be seen as an attempt to paint people who in practice are not necessarily possessed of huge talent as standing out from the crowd.

However, the reverse is usually the de facto reality: even if you want to be seen as an individual, that option will be stripped from you by association with others sharing at least one characteristic – and even more aggravating when the label applied is wrong. If you have been libelled in the press you have potential redress via the courts, but if the grapevine calls you something you’re not there is pretty much nothing you can do about it. Any attempt to correct a misapplied label will be taken as evidence that “the lady doth protest too much” and that, by implication, the truth is being covered up.

But rather than just being an identifier to society, sometimes the labels are never more than approximations but do give a measure of expectation. Why would that be necessary? Because judgement comes not from the person but from the label. One example I recall was a chap on the same degree course way back when, who was renowned as a member of the so-called “Militant tendency” group of extreme left-wingers operating within the Labour party – up to the point when they were expelled.

This chap, who I won’t name, had been mentioned in lists published by the Daily Mail and other right-wing media as one of a body trying to undermine everything we hold dear in the UK, that they should be jailed and goodness knows what else. The preconceptions from that label meant that a good number of people even within the university feared and hated him without ever knowing him.

In fact, he was nothing like the ogre painted in the press. He was a friendly, sociable guy who enjoyed music, would talk about anything, and was by no means intractable even about his political beliefs; if you made a good point he would acknowledge that. Whether he moderated his beliefs in later years I have no idea, but this experience proved to me conclusively that you should judge everyone on their own merits by getting to know a person and gaining a 360-degree perspective, never by believing labels, slurs and hyperbole.

My view is simple: judge people by who they are and how they behave. Never ever judge them by their skin pigmentation, their political affiliations, their religion, their creed, their culture, their age, their sexuality, their morals, their team or any other label applied to them. Treat as you find and never ever discriminate on the basis of pigeon-holes.

In my estimation that a worthy motto for this Century, though there is one label I will apply: those I am most likely to despise are small-minded bigots who go out of their way to hate for the sake of hating or because other people are “not like us.” We can well do without such petty prejudice for the good of mankind.