pol·i·tics (p l l  -t -t ks) n. ks) n.

1. (used with a sing. verb)

a. The art or science of government or governing, especially the governing of a political entity, such as a nation, and the administration and control of its internal and external affairs.

b. Political science.

2. (used with a sing. or pl. verb)

a. The activities or affairs engaged in by a government, politician, or political party: “All politics is local” (Thomas P. O’Neill, Jr.) “Politics have appealed to me since I was at Oxford because they are exciting morning, noon, and night” (Jeffrey Archer).

b. The methods or tactics involved in managing a state or government: The politics of the former regime were rejected by the new government leadership. If the politics of the conservative government now borders on the repressive, what can be expected when the economy falters?

3. (used with a sing. or pl. verb) Political life: studied law with a view to going into politics; felt that politics was a worthwhile career.

4. (used with a sing. or pl. verb) Intrigue or maneuvering within a political unit or group in order to gain control or power: Partisan politics is often an obstruction to good government. Office politics are often debilitating and counterproductive.

5. (used with a sing. or pl. verb) Political attitudes and positions: His politics on that issue is his own business. Your politics are clearly more liberal than mine.

6. (used with a sing. or pl. verb) The often internally conflicting interrelationships among people in a society.

Usage Note: Politics, although plural in form, takes a singular verb when used to refer to the art or science of governing or to political science: Politics has been a concern of philosophers since Plato. But in its other senses politics can take either a singular or plural verb. Many other nouns that end in -ics behave similarly, and the user is advised to consult specific entries for precise information.

|

The interesting thing about this definition is that politics is taken as high Politics with a capital P, government and administration, well ahead of its true day-to-day meaning for us all, namely the intrigue or manoeuvring within a unit or group in order to gain control or power – or, more to the point, to influence when and how decisions are taken. Office politics is the prime example, but the machinations of any group can and often are political.

Chicanery for political advantage in the widest sense takes place everywhere, quite apart from in the formal process of Politics – though that will happen from Parish councils right the way up to government and global talking shops. All, wherever they might be, will depend on negotiation and bargaining in order to get things done, which is how the real world politics came to be known, is Bismarck’s celebrated phrase as “the art of the possible.”

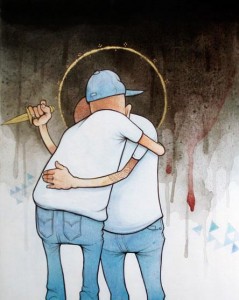

But no matter how noble or worthy the cause may be, ultimately the process and practice of politics is selfish, fuelled by the lust for power and control and to win for personal fulfilment. It is usually associated with those who will smile to your face while sliding the stiletto firmly in your back, particularly of people within your own team since they are your true enemies. Keep your friends close and your enemies closer, as the saying goes. Personal vendettas are played out on the big stage, and you don’t get far in any power-driven environment without picking up some enemies along the way.

Arguably that is just as true of local societies as it is of national politics. Some (though mercifully not all) amateur dramatics groups are among the most cliquish and political organisations I’ve ever come across, and inevitably they have among their midst the wounded and embittered losers from showdowns worthy of the Gunfight at the OK Corral. In these societies there are frequently busybodies who run the show with exaggerated efficiency, and in so doing make sure all their mates and allies get the best jobs and best roles.

Those who devote their lives to being the backbone of any party, society, club or organisation will tell you they are doing so purely out of duty and service to the community. Thinking back to parties, what they do when in power is almost secondary to the whiff of victory for having got there and stayed there.

To an alien flying in from another planet, this aspect of human behaviour may seem odd, if not perverse. If getting things done more effectively where the ambition, would it not make more sense to put aside personal enmities and rivalries, sacrifice ambitions and co-operate on matters of mutual interest? Why do we insist on competing and scoring victories when there is a greater good on which we could and should agree? Often, political manoeuvring seems to be more about opposition for the sake of opposition rather than because it is the most sensible thing to do.

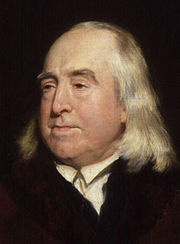

Jeremy Bentham‘s utilitarian philosophy is far from perfect (not least deciding what constitutes happiness for the greatest number, who should decide, how you achieve it, and what rights the minority who are not made happy should have), but his “fundamental axiom, it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong” does at least imply a need for selflessness in doing what is right.

But the very nature of ambition means people are advancing their own cause all the time. Natural competitive urge? Baser selfish instinct? Are we basically primeval creatures at heart, can we be characterised in the words of the infamous Gordon Gekko in the movie Wall Street: “Greed is good”? I’d argue not. Even among the most tyrannical despots there is evidence of some vestige of human feeling, some caring about the needs of others. We all care about some living creatures less fortunate than ourselves, though whether that be victims of famine or other natural disaster, people who are poor and struggle to get by, those who have fallen from grace, those in pain or who have lost loved ones in one way or another, animals in distress or whatever form of suffering it happens to be, we sometimes can be motivated to take some action to demonstrate our caring – even if it’s only to shove a few coppers in a collecting tin.

As a species we are quite capable of benevolent and selfless behaviour, and indeed of co-operating, but the irony of a democratic environment is that everyone wants to be a dictator in order to get their own way and not to have to involve other stakeholders in the decision-making process. Build a power base and you can dominate every aspect of life, if that is your modus operandi, even in organisations requiring a democratic constitution and a quorate vote at the AGM.

By comparison, the two am dram groups to which I now belong both bend over backwards to encourage new members and to enable them not only to participate in productions at the most appropriate level but also to assume positions of authority, if they are so inclined. A heartening sight to be sure, and arguably more effective by virtue of the variety of ideas and innovation that go into productions – not only a meritocracy but also enabling true learning and sharing of experiences. Is this not what we should focus on: the organisation being more important than any one individual in its midst?