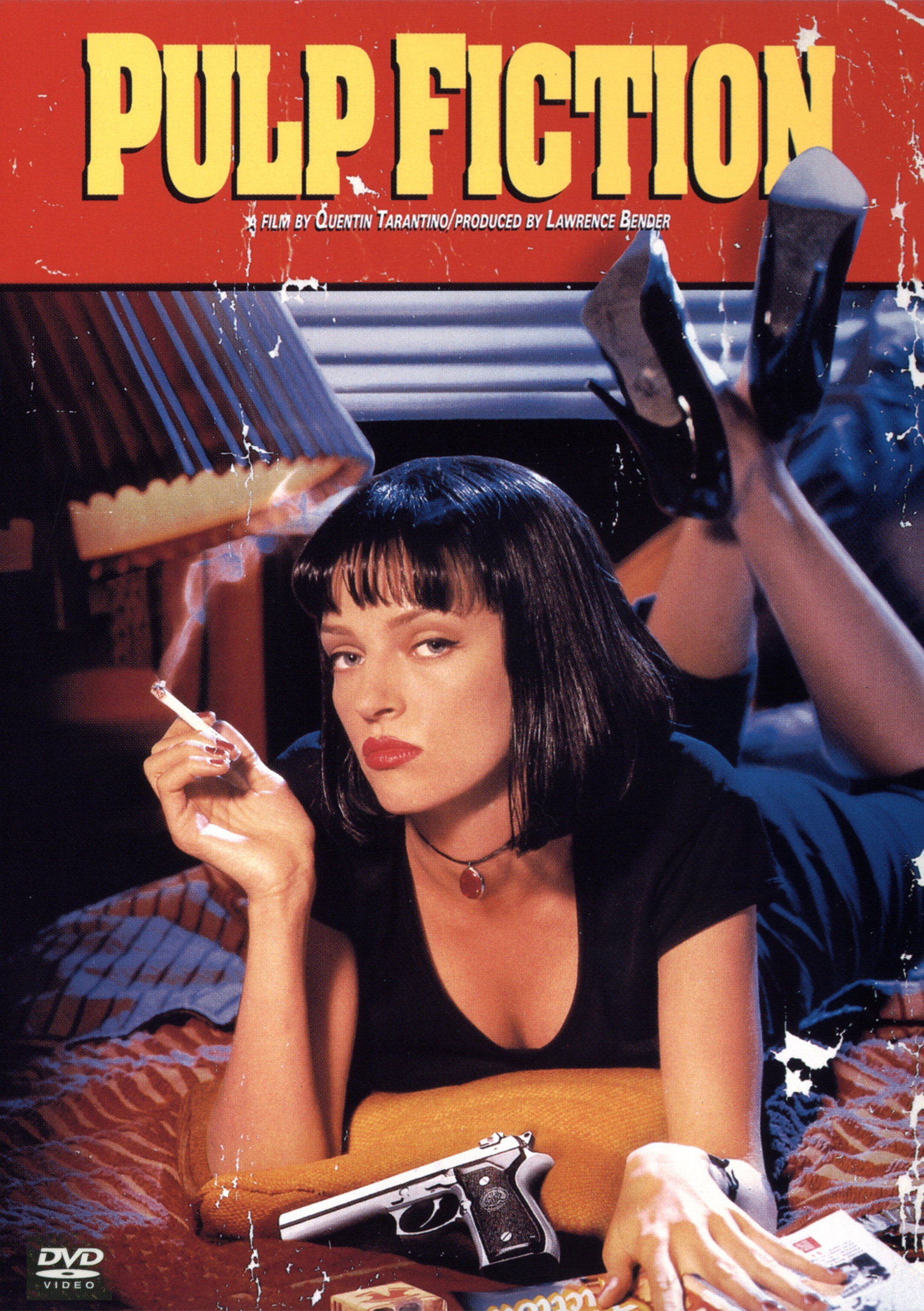

What is it that makes Pulp Fiction such an enjoyable watch: The action content maybe? The deliciously souped-up scripted street talk, dialogue courtesy of Tarantino and co-writer Roger Avary? The whacky surf and irresistible pop tunes on the soundtrack? The delicate non-linear construction of the timelines, such that the movie ends where it starts? The interweaving narrative tales of nasty but amusing criminal lowlifes around LA? A truly excellent cast and riveting direction? The inclusion of more magic moments, the sort that you remember for years rather than seconds, than you typically find in a dozen movies?

All of the above make Tarantino’s second feature magnetic viewing, the movie that sealed his reputation after the charismatic cult classic of a debut in Reservoir Dogs. This is a smart, sassy, oh-so-clever movie, yet strangely comforting to watch again, possibly because it bases its entire modus operandi on homage, nods to various genres, directors and actors. With Pulp Fiction, we lapped up the derivative exploitation that is QT, and through the assorted follow-ups, before knowing copies started to become tedious and repetitive.

Kill Bill‘s take on martial arts we’d seen before, not to mention Inglourious Basterds‘ Nazi hunters and Django Unchained‘s view of spaghetti westerns and slavery – though in all cases the fresh take on the genre was what made us watch. My personal favourite is QT’s version of blaxploitation, in the form of a fairly straight adaptation of the Elmore Leonard novel Rum Punch, namely Jackie Brown, but I’d be the first to acknowledge that without Pulp Fiction the stratospheric Tarantino career and ego would have lurked in low-level orbit.

The cult status thing definitely helped and being cool helped greatly. Ah, but then this is a now a movie exercising the febrile imaginations of film historians and academics. Consider this, courtesy of Wikipedia:

The picture’s self-reflexivity, unconventional structure, and extensive use of homage and pastiche have led critics to describe it as a prime example of postmodern film. Considered by some critics a black comedy, the film is also frequently labeled a “neo-noir.” Critic Geoffrey O’Brien argues otherwise: “The old-time noir passions, the brooding melancholy and operatic death scenes, would be altogether out of place in the crisp and brightly lit wonderland that Tarantino conjures up. [It is] neither neo-noir nor a parody of noir.” Similarly, Nicholas Christopher calls it “more gangland camp than neo-noir,” and Foster Hirsch suggests that its “trippy fantasy landscape” characterizes it more definitively than any genre label. Pulp Fiction is viewed as the inspiration for many later movies that adopted various elements of its style. The nature of its development, marketing, and distribution and its consequent profitability had a sweeping effect on the field of independent cinema. Considered a cultural watershed, Pulp Fiction’s influence has been felt in several other media, and it is widely regarded as one of the greatest films of all time. In 2013, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant”.

But for audiences it was about fabulous entertainment value rather than deeper analysis. We were hooked from the start and had our attention held right through to the closing credits, assuming the gory cartoonish violence and hefty drug use did not put off the more easily shocked.

The first hook was in the opening credits: Dick Dale and his Del-Tones’ rip-roaring 1962 recording of Misirlou, then came a bunch of smoking hot retro hits (Dusty Springfield‘s glorious white soul in Son of a Preacher Man, Chuck Berry doing You Never Can Tell in the brilliant Jack Rabbit Slim’s twist contest scene, Al Green‘s classic Let’s Stay Together and Maria McKee‘s haunting If Love Is A Red Dress), not to mention a bunch of whacky surf music and novelty hits by the likes of the Statler Brothers. Choosing a great soundtrack is a ploy that worked for many lesser movies, is a proven ticket-seller and identifies with its audience far more than the more traditional syrupy strings. It’s scarcely a new tactic, but QT took it to the next level.

Choice of cast also made a huge difference, which is why QT follows a well-trodden pattern of having his own repertory company, supplemented by cool actors who happen to be down on their luck and are therefore available relatively cheap. In Pulp Fiction, the former category included the charismatic Samuel L Jackson dominating the screen as Jules Winnfield, Tim Roth, Amanda Plummer, Uma Thurman, oh and Tarantino himself of course; the latter, Bruce Willis as Butch the boxer and John Travolta, late of Saturday Night Fever and Grease, but still looking great. Alongside Travolta’s role as junkie hit man Vincent Vega, hire talents like Christopher Walken, Harvey Keitel, Ving Rhames, Eric Stoltz, Rosanna Arquette and many more in vital cameos and you’ve built a star-studded line-up before anything hits the screen, and there’s nothing the publicists like better than a host of well-known names to plug a movie.

As for the Tarantino/Avary script, it succeeds where many fail in being both zingy and darkly funny. It goes off at tangents that you would not normally have anticipated in the scheme of noir-ish crime movies. What characters do and what they talk about are poles apart, such as Jules and Vincent talking about burgers on the way to a hit job. These might be tough guys, but they have a life outside work and talk about trivial stuff the way the rest of us do all the time – it is at once outside our experience, yet we can relate to it. It also has its unforgettable moments, the ones we never forget – like Jules’s recitation of Ezekiel 25:17 before killing the unfortunate victim, and later trying to interpret his intended meaning of the words. The soundbites we remember are legion:

- “Bring out the gimp“

- “Zed’s dead baby, Zed’s dead“

- “I love you Pumpkin” “I love you Honey Bunny“

- “That’s thirty minutes away. I’ll be there in ten“

- …and many more.

If the characters and the words are charismatic, the plotting is simply delightful, focused as it is on a series of riveting yarns, each from the point of view of one character, and beautifully interconnected with the overall schema. Each section is a minor gem in its own right. You’d be struggling to describe any as weak or ineffective. They could be sketches were they not married beautifully to the narrative structure of the movie. Wikipedia explains all:

“Prologue—The Diner”

“Pumpkin” (Tim Roth) and “Honey Bunny” (Amanda Plummer) are having breakfast in a diner. They decide to rob it after realizing they could make money off the customers as well as the business, as they did during their previous heist. Moments after they initiate the hold-up, the scene breaks off and the title credits roll.

Prelude to “Vincent Vega and Marsellus Wallace’s Wife”

As Jules Winnfield (Samuel L. Jackson) drives, Vincent Vega (John Travolta) talks about his experiences in Europe, from where he has just returned: the hashish bars in Amsterdam, the French McDonald’s and its “Royale with Cheese.” The pair—both wearing dress suits—are on their way to retrieve a briefcase from Brett (Frank Whaley), who has transgressed against their boss, gangster Marsellus Wallace. Jules tells Vincent that Marsellus had someone thrown off a fourth-floor balcony for giving his wife a foot massage. Vincent says Marsellus has asked him to escort his wife while Marsellus is out of town. They conclude their banter and “get into character” which soon involves executing Brett in dramatic fashion after Jules recites a baleful “biblical” pronouncement.

“Vincent Vega and Marsellus Wallace’s Wife”

The “famous dance scene”: Vincent Vega (John Travolta) and Mia Wallace (Uma Thurman) do the twist at Jack Rabbit Slim’s.

In a virtually empty cocktail lounge, aging prizefighter Butch Coolidge (Bruce Willis) accepts a large sum of money from mobster Marsellus Wallace (Ving Rhames) after agreeing to take a dive in his upcoming match. Vincent and Jules—now dressed in T-shirts and shorts—arrive to deliver the briefcase, and Butch and Vincent briefly cross paths. The next day, Vincent drops by the house of Lance (Eric Stoltz) and his wife Jody (Rosanna Arquette) to purchase high-gradeheroin. He shoots up before driving over to meet Mrs. Mia Wallace (Uma Thurman) and take her out. They head to Jack Rabbit Slim’s, a 1950s-themed restaurant staffed by lookalikes of the decade’s pop icons. Mia recounts her experience acting in a failed television pilot, Fox Force Five.

After participating in a twist contest, they return to the Wallace house with the trophy. While Vincent is in the bathroom, Mia finds his stash of heroin in his coat pocket. Mistaking it for cocaine, she snorts it and overdoses. Vincent rushes her to Lance’s house for help. Together, they administer an adrenaline shot to Mia’s heart, reviving her. Before parting ways, Mia and Vincent agree not to tell Marsellus of the incident.

Prelude to “The Gold Watch”

Television time for young Butch (Chandler Lindauer) is interrupted by the arrival of Vietnam veteran Captain Koons (Christopher Walken). Koons explains that he has brought a gold watch, passed down through generations of Coolidge men since World War I. Butch’s father died of dysentery while in a POW camp, and at his dying request Koons hid the watch in his rectum for two years in order to deliver it to Butch. A bell rings, startling the adult Butch out of this reverie. He is in his boxing colors—it is time for the fight he has been paid to throw.

“The Gold Watch”

Butch flees the arena, having won the bout. Making his getaway by cab, he learns from the death-obsessed driver, Esmarelda Villa Lobos (Angela Jones), that he killed the opposing fighter. Butch had bet his payoff on himself at favorable odds in a double-cross of Marsellus. The next morning, at the motel where he and his girlfriend, Fabienne (Maria de Medeiros), are lying low, Butch discovers that she has forgotten to pack the irreplaceable watch. He returns to his apartment to retrieve it, although Marsellus’ men are almost certainly looking for him. Butch finds the watch quickly, but thinking he is alone, pauses for a snack. Only then does he notice a machine pistol on the kitchen counter. Hearing the toilet flush, Butch readies the gun in time to kill a startled Vincent Vega exiting the bathroom.

Butch drives away, but while waiting at a traffic light, Marsellus walks by and recognizes him. Butch rams Marsellus with the car, then another automobile collides with his. After a foot chase the two men land in a pawnshop. The shopowner, Maynard (Duane Whitaker), captures them at gunpoint and ties them up in a half-basement area. Maynard is joined by Zed (Peter Greene) the pawnshop’s security guard; they take Marsellus to another room to rape him, leaving a silent masked figure referred to as “the gimp” to watch a tied-up Butch. Butch breaks loose and knocks out the gimp. He is about to flee, when he decides to save Marsellus. As Zed is sodomizing Marsellus on a pommel horse, Butch kills Maynard with a katana. Marsellus retrieves Maynard’s shotgun and shoots Zed in the groin. Marsellus informs Butch that they are even with respect to the botched fight fix, so long as he never tells anyone about the rape and departs Los Angeles, that night, forever. Butch agrees and returns to pick up Fabienne on Zed’s chopper.

“The Bonnie Situation”

The story returns to Vincent and Jules at Brett’s. After they execute him, another man (Alexis Arquette) bursts out of the bathroom and shoots wildly at them, missing every time before an astonished Jules and Vincent return fire. Jules decides this is a miracle and a sign from God for him to retire as a hitman. They drive off with one of Brett’s associates, Marvin (Phil LaMarr), their informant. Vincent asks Marvin for his opinion about the “miracle” and accidentally shoots him in the face.

Forced to remove their bloodied car from the road, Jules calls his friend Jimmie (Quentin Tarantino). Jimmie’s wife, Bonnie, is due back from work soon, and he is very anxious that she does not encounter the scene. At Jules’ request, Marsellus arranges for the help of his cleaner, Winston Wolfe (Harvey Keitel). “The Wolf” takes charge of the situation, ordering Jules and Vincent to clean the car, hide the body in the trunk, dispose of their own bloody clothes, and change into T-shirts and shorts provided by Jimmie. They drive the car to a junkyard, from where Wolfe and the owner’s daughter, Raquel (Julia Sweeney), head off to breakfast. Jules and Vincent decide to do the same.

“Epilogue—The Diner”

As Jules and Vincent eat breakfast in a diner, the discussion returns to Jules’ decision to retire. In a brief cutaway, we see “Pumpkin” and “Honey Bunny” shortly before they initiate the hold-up from the movie’s first scene. While Vincent is in the bathroom, the hold-up commences. “Pumpkin” demands all of the patrons’ valuables, including Jules’ mysterious case. Jules surprises “Pumpkin” (whom he calls “Ringo”), holding him at gunpoint. “Honey Bunny” (whose name turns out to be Yolanda) becomes hysterical and trains her gun on Jules. Vincent emerges from the restroom with his gun trained on her, creating a Mexican standoff. Jules reprises the biblical passage he’d recited at Brett’s place (Ezekiel 25:17), this time with sincerity rather than for effect. Jules expresses his ambivalence about his life of crime. As his first act of redemption, he allows the two robbers to take the cash they have stolen and leave, but they leave the briefcase behind for Jules and Vincent to return to Marsellus. Thus, Jules finishes his final job for his boss.

So there you are, a tale of redemption to please the sizeable US religious community into the bargain, and the gun lobby certainly wouldn’t be unhappy. This is not to say Pulp Fiction is perfect, but then a film without flaws has yet to be made. It is what it is, and loves to be loved for its quirky personality, a bit like a much-cherished eccentric uncle. It’s carried off with flair and pzazz by Tarantino, and ultimately that’s why it’s stood the test of time.