“Right now I’m a burden; I hope to be a self-sufficient cripple one day” – Frida Kahlo in Frida

The place is Mexico, the year 1925 or thereabouts. The 18 year old Frida Kahlo, who had already suffered from a bout of polio, meets for the first time her artistic hero, communist painter Diego Rivera, demonstrates her independence by posing for a family photo in a man’s suit, and suffers the appalling impact of a bus crash that defines much of her future life – the pain and ill-health she suffered henceforward, the artistic talent she had time to nurture while in a complete body cast, and, indeed, the perseverance to walk again when the medical fraternity thought to a man she was destined to be forever handicapped.

From there we learn of her gradual recuperation; then of how she develops a unique artistic style, albeit influenced by Rivera; of how she again meets and eventually falls into a turbulent relationship with Rivera; of how they marry, ironically; of his womanising and her affairs with men and women alike, including Leon Trotsky; of the rise of her career and the gradual decline of her health; and inevitably, her death.

Through their careers, Rivera and Kahlo remind you strongly of A Star Is Born by the way his slowly declines while hers takes off, posthumously for the most part. Kahlo is certainly worthy of a biopic for a life as colourful as her paintings, but her image has significance beyond the sanitised impression given by history, much in the same way that the iconic representation of Che Guevara lost its political significance to all those who hung the poster on their walls in the decades since his death.

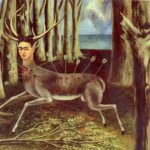

In hindsight, Kahlo created images that define the culture and society of Mexico, many surrealistic self-portraits strongly imbued with the symbolism of Mexican life (eg. the skeletons giving a nod to the day of the dead) and deeply personal images and metaphors about her life, many of which are woven into the film in an evocative visceral, visual language designed to explore the nature of the metaphors in her paintings. The psychology would have given Freud a field day. Wikipedia gives you a flavour of how reality and recreation have been loosely woven together:

The passengers on the trolley Kahlo rides and that crashes with a bus are based on subjects in the painter’s 1929 portrait, The Bus. The Brothers Quay-created stop motion animation sequence depicting the initial stages of Kahlo’s recovery at the hospital after the trolley accident are inspired by the Mexican holiday Day of the Dead. The gown Valeria Golino wears at Kahlo’s 1953 Mexican solo art exhibition is a replica of the dress her character Lupe Marín wore in Rivera’s 1938 portrait of her.

This is mirrored by a backdrop of a highly colourful and flamboyant Mexico, locations apparently including the blue house in Mexico City, fine recreations of Kahlo’s paintings, and remarkable stagings of events from her life (the only time I ever saw a bus crash staged better was in House series 4.)

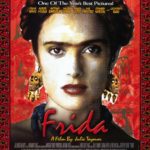

All this sounds great, but what we are left with is a series of colourful events, a beautifully drawn character study, authentic to the period and beautifully crafted but in the final analysis slightly duller than its subject or her paintings. Given an unconventional lifestyle, this is for the most part a relatively straightforward and linear narrative – contrary to the modern trend for deliberately weaving fact and fiction, playing games with time signatures, playing tricks with established facts in order to cast a dramatic slant.

Granted that Frida encompasses its own stylised mid-section as the couple tour the US of A, but in the hands of director Julie Taymor it never truly explodes on the screen in the way you might expect – and in that respect it reminded me of the dramatisation of another great artist, Mr Turner. It seems the writers (4 of them) grappled with but ultimately failed to bring the subject matter to life. The finished result lacks coherence and narrative bite. It meanders without true purpose or drive.

Perhaps more development of Frida’s technique or psychology in developing her works of art might help to create effective parallels, and less focus on her relationship with Rivera, particularly how she subjugated her work to his career and needs, might have kick-started the movie? You may disagree, though I also found that making the characters speak in Mexican-tinged accents added nothing but did sound faintly absurd.

Salma Hayek does a splendid job of creating a likeness of the painter, aided by a “make-under” (Kahlo evoked deeply passionate sexual feelings in her partners, but I doubt any thought her a great beauty), and clearly has a passion for her subject. As a performance, it did not rip up any trees but is a solid job, as indeed are most performances on view – albeit the leading lights seem to age very late and very suddenly, which I will put down to a make-up malfunction.

Acting honours in this production must however go to three ageing men in the cast: Alfred Molina is spot on as Rivera – but then he always is; the late Roger Rees as Kahlo’s father Guillermo also hits the right notes, another fine and reliable British character actor; and the splendid Geoffrey Rush as a rejuvenated but eventually assassinated Trotsky. Damn that Stalin!

Along the way we also meet Nelson Rockefeller (Edward Norton playing the dissatisfied client of Rivera) and Josephine Baker (Karine Plantadit – entertaining for Frida in more ways than one) – good at least for novelty value. Oh, and Antonio Banderas playing… Antonio Banderas, sorry, David Alfaro Siqueiros.

All watchable but somehow the ingredients contrive to be less than the sum of their parts, more’s the pity. No question that Kahlo and her paintings are utterly fascinating, but somehow the film does not do her or them true justice.