This is a film about the events everyone who was old enough at the time to remember recalls in vivid detail, just as a later generation remembers with shuddering clarity what they were doing on 9/11. In my case I didn’t hear the news on JFK’s demise with understanding, but then it was my 4th birthday so I’ve always felt a small personal association. What more can possibly be said about the JFK assassination, I hear you ask. After all, there have been more words written about this death than almost any other in human history, more films, more theories and more truths hidden. Do we really need another?

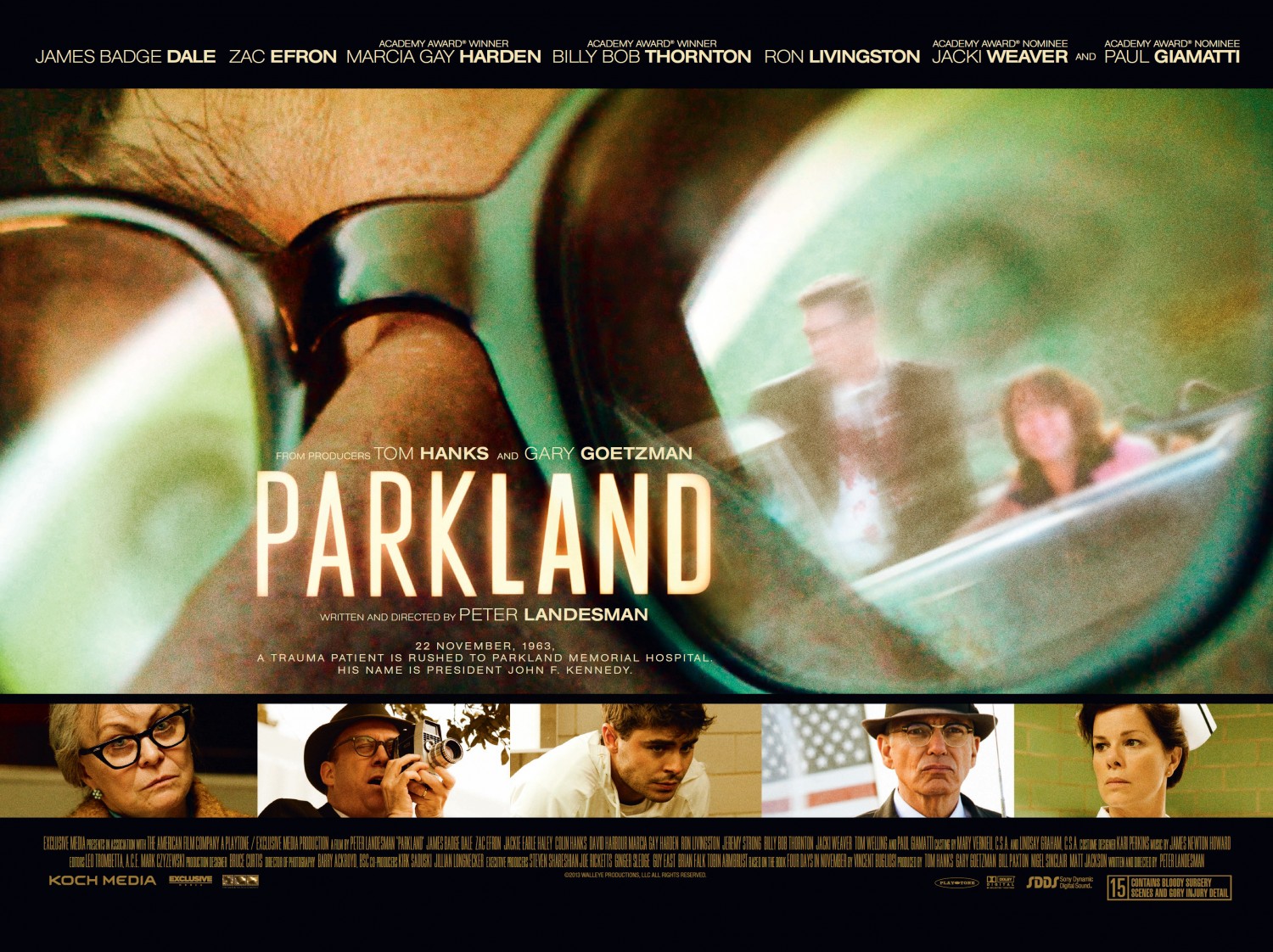

Parkland, whose name refers to the hospital where both Kennedy and his assumed assassin breathed their last, is the latest telling of a well-told tale, brought to the screen by a quintet of producer including none other than Tom Hanks and Bill Paxton. Where others come down on one side or other in the assassination debate, Parkland takes an entirely different tack, being a brief study of the lives of those impacted by the assassination in its immediate aftermath and embroidering little on to well-documented truths, but for plausible dialogue. Parkland is concerned with the human touch, the emotional vacuum and the recriminations trailing in the wake of the biggest trauma to strike the American nation in generations, the story of “what happened next” rather than the truths within.

This is a slight and slightly off-centre film about momentous events, told in mock-doc style with lots of wobbly hand-held footage and at times a muted, understated acting style, infinitely preferable to gross melodrama and overacting, indicative perhaps of the shock waves resulting from the slaying of a president on prime American soil. Granted there is a second DVD telling of the Warren Commission and the very many conspiracy theories – ranging from the potentially accurate to the bizarre and obtuse, but that is not the business of Parkland.

The stories to be told are tragic, such as the doctor, Jim Carrico (Zac Efron escaping from his typecast stereotype) who furiously pumped the presidential chest long after he had given up the ghost, and in spite of the gaping head wound from which no survival was remotely possible; such as the bewildered secret service men (including Billy Bob Thornton, Tom Welling, Ron Livingstone and Austin Nicholls), who lost their man on their watch and also had Lee Harvey Oswald in their office 10 days earlier but let him go; such as the dignified brother and shrill mercenary mother of Oswald (respectively James Badge Dale and Jacki Weaver); and of course Abraham Zapruder (Paul Giametti), the man whose cine footage recorded the moment of Kennedy’s death in graphic detail and who was thereafter traumatised by the accidental zeitgeist of his actions. Look out also for fine actors such as Marcia Gay Harden and Colin Hanks, not to mention characters as familiar as Lyndon B Johnson and Jackie Kennedy.

The cast is quietly effective. Regular readers will know I’m highly partial towards Paul Giametti, but within context all of the real-life characters look and sound plausible, with the exception of a wooden Oswald and the possible inside story, towards which he and his mother make dark hints that are never explored further, notably that Oswald was recruited to the US Secret Service.

There is a deliberate fuzziness at the heart of the movie the characters struggle to mind meaning from what their eyes and senses tell them and from the buzz of speculation that follows on close behind. The first lady moons about the trauma suite in shock and awe, not able to tear herself away, strangely fascinated with the vain attempts to save her husband’s life, but simultaneously repulsed and horrified. As Zapruder films the events and the world looks towards the car and Jackie trying to escape by crawling over the back of the car, there is a man distinctly shown running away from the “grassy knoll” area – though the director never delves any further.

What I like about Parkland are the beautifully made, very plausible and faintly absurd and tragic touches: seats being ripped out of Air Force One so the president’s coffin could travel up top rather than in the baggage hold – and then a bulkhead sawn off so the coffin could fit in through the doorway; the press men being invited to help with Oswald’s coffin because nobody would act as pall bearers for the man they believed, rightly or wrongly, to be the lone gunman; and the childish argument about who has jurisdiction over the body. At times like this the minute observations say most, and it is a strength of this movie that these and many more such moments stay long in the memory.

This film adds background and context, light and shade to to JFK story, though it is a story best heard at face value, allowing others, including Oliver Stone‘s JFK, to provide interpretation. Maybe someday someone will try to stitch together the complete picture and a different view will emerge?

Excellent read, I just passed this onto a colleague who was doing some research on that. And he actually bought me lunch since I found it for him smile So let me rephrase that: Thank you for lunch!