I’ve wondered aloud on other occasions about what makes a movie an authentic classic. A star-studded studio budget fest certainly is not the answer since that is frequently a shortcut to howlers and razzys as it is success; nor is cult status a synonym for classic status either. The Star Wars franchise are hugely popular but are they worthy of being described as “classics”? Some would say so, though I would beg to differ.

Strangely, classics don’t have to be the most innovative films, nor necessarily the best acted – though you only need to look at Citizen Kane to know that in many cases they are iconic for both. Me-too copies seldom grace like the originals, one reason why Brief Encounter is timeless but hundreds more of the same era failed to capture the bittersweet mood and a place in our consciousness. They descend into obscurity where the classic is always remembered.

So here is Millward’s recipe, which does not mean it can be repeated as a formula, quite the contrary. It takes something exceptional to make a classic, as follows:

1. Brilliant source material dealing with timeless themes, which would explain the enduring appeal of classical Greek theatre and Shakespeare too. Adaptations or original scripts could equally apply.

2. Depth of meaning: such human and psychological complexity of emotion and mood that it can be interpreted in more ways than one, and certainly stands repeated viewings.

3. The themes and dialogue stand in their own right, including memorable scenes. They are never drowned out by the action or special effects but are quotable in their own right.

4. The acting and direction has charisma and presence. The performers are at the top of their game, such that the eye lingers in each in turn. One does not drown out the rest, but together in an ensemble they form a symphony, the sum of the parts being greater than each individual contribution.

5. The ending does not cheat the audience but leaves sufficient ambiguity that there are different potential outcomes.

6. The film gains a momentum and reputation far in excess of its original reception, possibly as an allegory for wider society. If anything, the reputation grows over time and in hindsight.

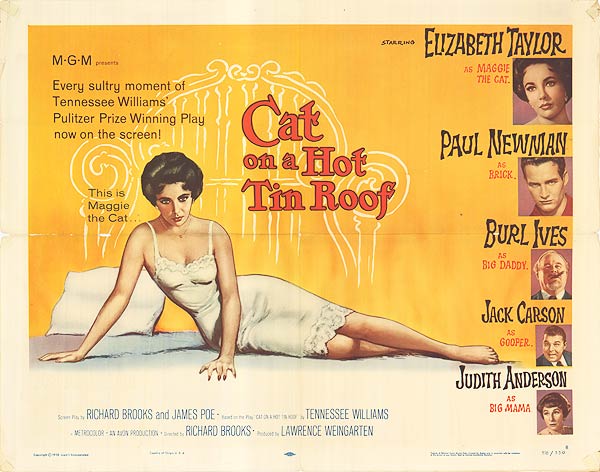

Cat On A Hot Tin Roof is undeniably a classic, though chances are many over the years would have dismissed it as a melodramatic Pollitt family squabble. No question though, it has incredible presence and themes that are timeless, especially the metaphor of the crumbling empire. While the adaptation of Tennessee Williams‘s play slightly opens out the action, essentially it is a wordy and claustrophic piece, but you can also look beyond the words and see a power struggle worthy of the bard’s political masterpieces, of Pinter, of Beckett, of Miller‘s Death of a Salesman, of all the greatest plays focusing on the battle for territorial dominance.

In this case it is the declining southern plantation-owning patriarch, Big Daddy, played at times with ferocious intensity by the great songster Burl Ives, with his sons Brick (Paul Newman) and Gooper (Jack Carson) and their respective wives (Liz Taylor as Maggie “the cat” – glamorous and sexy but with one small issue, as we will see) and shrill prolific mother Mae (Madeleine Sherwood.)

The issues at stake are Big Daddy’s fading powers and terminal cancer, which he and Big Mama (Judith Anderson) would sooner gloss over in a wave of faux-positivism; of Brick’s failing marriage, alcoholism and depression as injuries have put an end to his promising sporting career; and of the dim-witted Gooper’s loyal and dutiful support of Big Daddy. Assuming Big Daddy recognises that he is on his last legs, which son, if either, is capable of continuing the dynasty as the next patriarch?

The stage is set and the stars give it full justice, though what you see are their respective failures. Gooper lacks the wherewithal, the leadership and dominance, so Big Daddy wants Brick to step up to the mark, but Brick is not playing ball – stopping him drowning sorrows in a fit of nihilistic rage is only the first step, which in turn leads him to question how effective his own parenting ability has been. Each player has a part to play, and each has their turn in the spotlight as the mood waxes, wanes and ultimately reaches a dramatic crescendo, a moment of truth and understanding.

Ives is brilliant as the bullying and irascible Big Daddy and Newman his equal by turn, correctly avoiding the trap of appearing drunk, thus being more credible as an authentic alcoholic. Taylor’s Maggie is almost playful and childish at times, yet possessed of a backbone and prepared to stand up to her husband and his father alike. By comparison, Gooper, Mae and Big Mama almost fade into the background, being the dutiful and loyal servants of Big Daddy, boring even to him.

“I don’t want things,” says Brick as he smashes some of Big Mama’s accumulated assets in a fit of rageful vengeance, including a canvas with a photograph of him as quarterback throwing the ball. In spite of his reactions, you see in Big Daddy’s eyes a sudden warmth and connection with his son. It is this moment of magic, among others, that demonstrate the credibility of human reactions portrayed.

It is this level of sophistication, the existence of a subtext whereby you, the viewer, can read into this domestic catastrophe at many levels that makes this such a perpetually relevant drama. Check it out: all 6 criteria are met, and big time. This is not the sort of drama that would please everyone, but it certainly stands out and will be remembered for as long as theatrical and cinematic culture is important in our society.

And yet…. Williams won a Pulitzer Prize for his play but was not apply with this adaptation of his screenplay. Wikipedia tells the story of this and the reception of the film:

Tennessee Williams was reportedly unhappy with the screenplay, which removed almost all of the homosexual themes and revised the third act section to include a lengthy scene of reconciliation between Brick and Big Daddy. Paul Newman, the film’s star, had also stated his disappointment with the adaptation. The Hays Code limited Brick’s portrayal of sexual desire for Skipper, and diminished the original play’s critique of homophobia and sexism. Williams so disliked the toned-down film adaptation of his play that he told people in the queue, “This movie will set the industry back 50 years. Go home!”

Despite this, the film was highly acclaimed by critics and audiences alike and it received six nominations for Best Picture, Best Actor (Newman), Best Actress (Taylor), Best Director (Brooks), Best Writing, Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium, and Best Cinematography, Color (William Daniels). Cat may have been too controversial for the Academy voters; the film eventually didn’t win any Oscar and the Best Picture award went to Gigi, another Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer production, that year. Ives won the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for The Big Country at the same ceremony.

In short, the film changes the character of the play but was still rewarded – albeit not as greatly in retrospect as you would have expected. Note that without the inference of a homosexual relationship with the late Skipper, Brick’s eschewing of his glamorous wife Maggie, Big Daddy’s mockery of him, and Brick’s alcoholism make far less sense. Without the sexuality there is a gaping hole in the soul of the drama, but knowing that omission does not make it any less of a classic.

Indeed, in accordance with (6) above, the reputation of the film has grown considerably over the years, and with good reason, though any remake of the 1958 film would be a very different film since it would take into account Williams’s intentions in respect of very different modern sensibilities (for the record, I did not see the 1984 made-for-TV version starring Jessica Lange, Tommy Lee Jones and Rip Torn, though Wikipedia helpfully points out, “this adaptation revived the sexual innuendos which had been muted in the 1958 film.”)

But equally the controversy attached only adds to the meta data and fascination with the movie as it was constructed and what nuances of meaning can be overlaid. Our greater knowledge of the context only enhances the classic status of the film. This is a significant step in the history of the cinematic and dramatic arts.