“Would you have me false to my nature? Rather say I play the man I am” – Corialanus

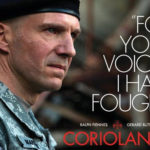

Ralph Fiennes has done a fine debut directorial job of translating to the big screen one of Shakespeare’s most political and bloodiest tragedies, and indeed of playing the archetypal antihero – though Vanessa Redgrave comprehensively steals the show, of which more later.

This film is pretty much the same length as the Fassbender-led retelling of Macbeth seen and reviewed recently, but comes over as a wholly more effective narrative – even if this parallel version of Rome seems to bear greater resemblance to sarf London, including police who appear very like British bobbies. In fact, the whole plot is redolent of the political and military crises of recent decades, and of the ruthless two-faced cynicism of politicians we all know and hate.

I have no doubt it is quite deliberate that the parallels to British society are very nakedly obvious, though Volsci has equally been transposed into Serbia, Serbian actors and all, under the military leadership of a pensive Gerard Butler as Tulles Aufidius.

Caius Martius gains his toponymic cognomen, far more than just a nickname, “Coriolanus” from General Comenius (John Kani) to reflect his exceptional valour in the Roman siege of the Volscian city of Corlioli. Martius is a warrior of great distinction but uncomfortable with both the trappings of politics and with the whole notion of democracy when senior people and his formidable and controlling mother Volumnia (Redgrave) push him into the role of Consul of Rome. He feels comfortable with war but rails against peace with a passion:

“Let me have war, say I; it exceeds peace as far as day does night; it’s spritely, waking, audible, and full of vent. Peace is a very apoplexy, lethargy: mulled, deaf, sleepy, insensible; a getter of more bastard children than war’s a destroyer of men.”

Indeed, the very notion of appealing to public sympathies is a complete anathema to Martius; he compares allowing citizens to have power over the senators as to allowing “crows to peck the eagles.” It is this conflict that allows scheming tribunes Brutus (Paul Jesson in a role that would have been tailor made for the late Ray McAnally) and Sicinius (the usually jolly James Nesbitt), fearing that he would bypass the Senate and assume dictatorial power, to plot accusations of treason against Martius and cause his expulsion from Rome:

“Despising, for you, the city, thus I turn my back: There is a world elsewhere.”

From there he hikes to Volsci and in Antium presents himself to his erstwhile enemy, Tulles Aufidius. Martius offers his life but what he truly wants is the chance to attack the city/state that betrayed him, in his eyes.

Embraced by Aufidius, he leads a force to Rome, where the protestations of Generals and Senator Menenius (wonderful to see Brian Cox cast in the role and applying his skills with panache) are water off a duck’s back – but ultimately his mother’s pleading causes Martius to relent and to negotiate a peace treaty with Rome, for which treachery he is killed by Aufidius’s men. The essence of this tragedy is the dichotomy within Martius: he loves his family and deep down he can’t totally disown his true home, no matter how much he despises Rome and its citizens for their treatment of him.

Fiennes brings to the role both the nobility of a man born to lead and the intelligence to bring out a deep-seated tragic unease with the grim inevitability of his fate. He knows his death will happen and does nothing to prevent it – indeed, it is the only honourable end for a warrior, but he cannot bear the prospect of dying in ignomy or disgrace.

The Martius Achilles heel is his subservience to is mother. To play this role with such power, poise and poignancy takes an actress of rare skill and calibre. You could imagine a Judi Dench or a Meryl Streep taking on Volumnia, but Vanessa is truly up there with the best actresses of her generation, one with the heritage to bring Shakespeare to life.

Redgrave’s performance brought tears to my eyes, such was the intensity of emotion – dominant and controlling when schewing her son’s career, voice drenched in betrayal when she feels wronged. There are not many sons, dutiful or otherwise, who could resist the entreaty of a harridan like Volumnia in full flight.

“For myself, son, I purpose not to wait on fortune till these wars determine. If I cannot persuade thee rather to show a noble grace to both parts than seek the end to one, thou shalt no sooner march to assault thy country than to tread on thy mother’s womb… that brought thee to this world.”

Martius’s meek and mild wife Virgillia (Jessica Chastain) can at times barely get a word in edgeways, such is his mother’s control, but she wants her man to pay attention to her and their son; you somehow feel he would sooner go to war.

Butler’s Aufidius also appears more phlegmatic than you might expect for a warrior and leader, such that his psychology in forgiving the man who defeated him in battle. Compared to Martius, he may be a man of few words and less of a natural leader, but makes his presence felt when required. Ultimately, it is his justice that prevails when his orders are denied.

This translation of a Shakespearian drama works most of all because it stays true to the essence of the characters and their fate, resisting the urge to allow the modernistic flourishes to dominate, as they might easily do. Fiennes certainly gives the parallels their head, but never does he stray too far from the text in the process, and a good thing too.

That the themes are timeless is echoed both by the frequency with which war and peace (or indeed War and Peace) feature in screen dramas, but also the prophetic nature of Shakespeare’s words. It’s as if he can see the future fickle nature of democracy, the lust for war and the use of xenophobic nationalism to justify political treachery.

See this film both for the director/actor, for Vanessa Redgrave, but most of all for Shakespeare – our true hero.