One person in every four suffers from a mental illness at some point in their lives. Remember that statistic!

This novel was dreamed up while author Ken Kesey worked on the graveyard shift at a psychiatric hospital. Kesey was a remarkable man: “I was too young to be a beatnik, and too old to be a hippie,” as he once said, but he lived life to the full. One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest was his best known and most remarkable novel. The derivation of the title is worth repeating here, via an answer posted on Yahoo:

“To understand the significance of the title of the novel ‘One flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest’ brainstorm everything you know about Cuckoos. For example, the fact that they don’t build their own nest, they kick out the other chicks when they are born, they are fed by a bird who is not their real mother. Can they see how this relates to the novel?

“The title is clearly allegorical in its intent. The “cuckoo’s nest” is the hospital, and the one who “flew over” it is McMurphy. The full nursery rhyme is quoted in Part 4 by the chief, as he remembers his childhood while awaking from a shock treatment. It was part of a childhood game played with him by his Indian Grandmother:

“Ting. Tingle, tingle, tremble toes, she’s a good fisherman, catches hens, puts ‘em inna pens…wire blier, limber lock, three geese inna flock…one flew east, one flew west, one flew over the cuckoo’s nest…O-U-T spells out…goose swoops down and plucks you out.”

As a movie Milos Forman‘s adaptation of OFOTCN achieved the rare distinction of being the second movie to win the “big five” Oscars and 33 on the list of all-time greatest movies listed by the American Film Institute, but more to the point it remains, 35 years on, one of the most moving and poignant films in the history of the industry, demonstration both of quality raw material and fine craft from everyone involved.

It would be easy to regard the material as an often shocking expose of the treatment of patients in a secure institution (in this case Oregon State psychiatric hospital, also where the novel was set) and the sometimes subtle, sometimes vicious means of control meted out to residents. Given Kesey’s background with the Beat Generation it would be just as easy to read the hospital as an allegory for the state and the use of authoritarian control to suppress its citizens, but at heart and at face value it remains an intensely and agonisingly powerful human tragedy. That is its strength and that is what stays with me enduringly.

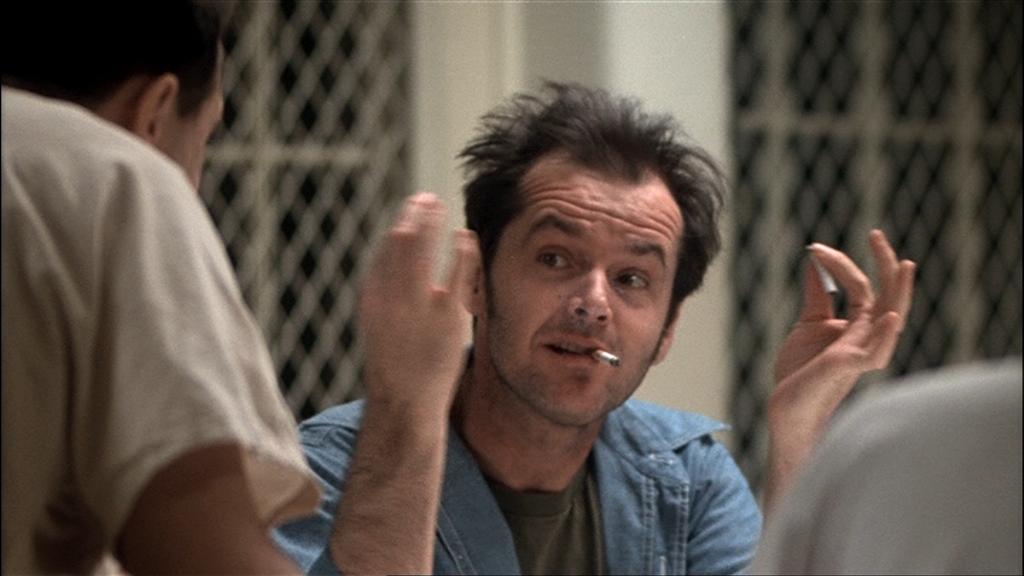

The agent of misfortune as much as change on the nuthouse is not a nut at all but a remand prisoner in the person of Jack Nicholson‘s RP McMurphy sent to the hospital for psychological evaluation. Up to his arrival the inmates had been a docile, unrebellious rabble, ruled with a rod of iron by “cold-hearted tyrant” Nurse Ratched (Louise Fletcher.) McMurphy and Ratched are the main two protagonists, one concerned with efficient management and the other with inspiring fun and freedom among the troops. Ratched’s control over the timid and nervous Billy is a key turning point, of which more shortly.

The movie is fuelled by the conflict between Ratched and McMurphy, ratcheting up with each subsequent challenge and response, at first little things like the taking of medication and having the volume of music turned down. The inmates, bullied and intimidated as they are, have had their humanity sucked from them. From Wikipedia:

McMurphy’s ward is run by steely, unyielding Nurse Mildred Ratched (Louise Fletcher), who employs subtle humiliation, unpleasant medical treatments and a mind-numbing daily routine to suppress the patients. McMurphy finds that they are more fearful of Ratched than they are focused on becoming functional in the outside world. McMurphy establishes himself immediately as the leader; his fellow patients include Billy Bibbit (Brad Dourif), a nervous, stuttering young man; Charlie Cheswick (Sydney Lassick), a man disposed to childish fits of temper; Martini (Danny DeVito), who is delusional; Dale Harding (William Redfield), a high-strung, well-educated paranoid; Max Taber (Christopher Lloyd), who is belligerent and profane; Jim Sefelt (William Duell), who is epileptic; and “Chief” Bromden (Will Sampson), a silent American Indian of imposing stature believed to be deaf and mute.

McMurphy instils in them a spark of life, makes them remember for brief moments the joy of living, notably by scheming an exit long enough to stall a hospital bus to take the group on a fishing trip, then by organising a party, inviting female friends and bringing liquor. He challenges the group in other ways, notably when he discovers most are voluntary patients who could walk out at any time.

The threat he causes to the established order has to be nipped in the bud for fear of anarchy. Initially he is given ECT, but eventually he, the sanest in the group apart from the chief, is lobotomised. The clear message is that treatments applied to those with mental illnesses are not to cure but to control. Inevitably, as with any battle for control between intransigent forces, there has to be a winner and a loser, and this is ultimately a battle McMurphy could not win.

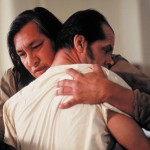

His metaphor for escape is a large plumbing fixture that McMurphy tries but fails to lift with the intention of throwing it through the barred windows and walking out of the hospital. He loses the bet but parts with the words “at least I tried.” It is highly symbolic that at the very end of the movie, that is exactly what the “chief” does en route to escape after suffocating McMurphy following his lobotomy. From the death of inspiration comes new hope.

For this to work, a very strong cast was essential, and this cast delivers powerfully but with sympathy. Apart from the sheer muscular power of performances by Nicholson and Fletcher, both of whom justly won Oscars, I am particularly impressed by Brad Dourif‘s traumatic screen debut as the nervous and stammering Billy, hounded to suicide by Ratched in an act that drives McMurphy to attack her.

Also worth noting is Will Sampson‘s dignity as the chief, playing deaf and dumb while actually as sane and lucid as McMurphy. In fairness, it is churlish to pick out any member of this cast since their roles demand not only convincing individual portrayals of troubled people but also realistic interaction and blossoming under the influence of McMurphy. They do far better than mere competence. This is superlative acting, naturalistic but focused, the sort of acting that repays viewing not once, not twice but multiple times, the sort of acting in which nuances will continue to surface no matter how many times you see the film.

If you’ve not seen OFOTCN and are put off by the uncompromising subject matter, don’t be. It should be faced head-on by everybody, but it will give you food for thought no matter who you are and what your attitude to mental illness. One Flew Over... is every bit as relevant today, given the shameful mistreatment of mental health by successive governments.

Nice read, I just passed this onto a colleague who was doing some research on that. And he actually bought me lunch because I found it for him smile So let me rephrase that: Thanks for lunch!

Usually I don’t read post on blogs, however I would like to say that this write-up very forced me to try and do so! Your writing style has been amazed me. Thanks, quite nice post.