“Sol Nazerman – the walking dead”

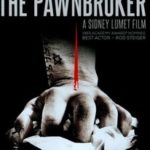

Sidney Lumet’s career took in some great highs and a few dodgy lows. Consider that this man’s directing debut was the classic 12 Angry Men, and his career extended to powerful films such as Network and Equus but also a fair sprinkling of plodding dramas and thrillers. However, none was more innovative, celebrated or powerful than his often overlooked 1964 film The Pawnbroker, remarkable in several particulars. One such is the undemonstrative yet hugely authoritiative eponymous performance of Rod Steiger in the role that won him A-list status in Hollywood.

How so? Because this is the story of an ex-professor who survived a Nazi death camp, losing his family in the process, then spends years suppressing the indelible memories while working as a pawnbroker in the poorest neighbourhood of east Harlem. As such it was the first film tackling the holocaust head-on from the perspective of a survivor, and in the process the first film dealing with what we now know is PTSD, not that it is named, nor was even recognised back in 1964.

The other historical curiosity is that this was the first approved film to include part female nudity (ie. bare breasts), though to say this gives entirely the wrong impression of the film – it is critical to the plot, is not remotely salacious or titivating, and is handled with sensitivity and humanity. Rather than take advantage, Steiger’s Nazerman covers up “Ortiz’s girl” (Thelma Oliver aka Krishna Kaur Kalsa.) He is not interested in sex, nor indeed in any person, not even his family.

The real issue with this character is that he can’t suppress the memories: they come back in subliminal images, recalled trough the sight of, for example, a black youth being beaten up by a gang. Sol Nazerman comes over as indifferent bordering on cruelly dispassionate. His denial of emotional involvement comes from years of trying to forget, though when pushed he snaps back with disdain, rarely revealing his internal suffering.

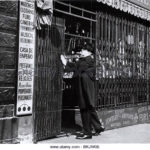

“You’re a mighty hard man,” says his Puerto Rican assistant, Jesus Ortiz (Jamie Sánchez.) He is not a man who discriminates, nor does he believe in anything but money – in spite of his pawnshop, the place where Nazerman judges the value of everything, losing money. There is a deliberate parallel with The Merchant of Venice, though whether Shylock has experienced the same spiritual death as the soulless Nazerman is doubtful. Money is the only thing left for Sol to deal with – nothing else matters to him, for there is nothing left to help him keep going.

He has dulled his soul to the extent that he can share no warmth or empathy for Tessie (Marketa Kimbrell), the woman who cares for him, shows him kindness and is met with disdain and ignorance. But ultimately he can’t escape feeling. As he puts it, the memories and the words return, mostly in the form of subliminal flashbacks as modern images echo the past.

After he rejects Tessie totally, she still allows him into her apartment; rather than apologising, Nazerman tries to articulate his memories of the concentration camp, losing his family and being totally powerless to change it. Tessie offers him a hand, which in a symbolically poignant and powerful moment he rejects and wanders out of her home, unable to bear the thought of letting another human being into the depths of his despair.

But two final moments of redemption are still to come: Nazerman refuses to sign his business away to menacing pimp and racketeer Rodriguez (Brock Peters); when Rodriguez and heavies come round to the shop, Nazerman double dares them to kill him, which the astute gangster realises will cause more suffering to resist.

Finally, when Ortiz’s homies try to rob Nazerman, he refuses to hand over the money, again daring them to kill him. But it is the loyal Ortiz who takes the bullet and dies as the gang scarpers. The intensity of Nazerman’s suffering can be felt in a chilling moment as he deliberately forces his hand down on the spike used to hold pawn receipts. Here is a man beyond saving.

The film is beautifully shot in black and white, giving a gritty and grainy feel to bring texture to the pawnbrokers shop in particular – credit to Boris Kaufman‘s cinematography, for which he was outrageously not even nominated for an Oscar. The Quincy Jones soundtrack (ditto with Oscar nominations) is bright, shiny jazz with a very angular 60s New York feel to it, a counterpoint to the introverted misery harboured by its leading protagonist.

In view of subsequent films covering similar ground (you know them all – no point in my listing any!), and the passage of time rending the sheer volume of appalling atrocities mere history lessons, maybe the potency of the subject has gradually declined, but there is no denying the ability of Morton S Fine and David Friedkin’s adaptation of Edward Lewis Wallant‘s novel, nor yet of how Lumet exploited the subject to greatest emotional impact – precisely by containing emotions, bottling them up except for a few key scenes where Steiger’s Nazerman allows his burden carried around for year after solitary year to be briefly released, then rebottled. Nobody else can see the grief, though the camera intrudes into these moments, a silent witness.

This is a masterpiece. Time it was revived for the benefit of modern audiences.