Authentic classics don’t often get remade, and To Kill A Mockingbird is one such, thankfully. This is a story told primarily from the perspective of Jean-Louise “Scout” Finch, a tomboy coming to terms with reality and the nature of justice in Alabama during the depression years of the 30s. The film is narrated by the adult Scout, looking back from the early 60s.

Like many of the best tales, it and the original novel by the late and revered Harper Lee is a simple story simply told, one about coming of age, justice and injustice in the Deep South – oh and the legend of the mythical Boo Radley (a character with a pop group named after him – see here.) It tells of how attitudes are formed and how we come to see people for who they are not what we are told to think of them.

Certainly one motive behind book and film is to expose naked racism, which makes it all the more ironic that To Kill A Mockingbird and Huckleberry Finn have been excluded from some Virginia county school libraries precisely for including racist language deemed to be offensive, in spite of both books being texts demonstrating the evils and hypocrisies of racism. If ever you needed evidence that society has its values back-to-front, this is surely it (see here.)

In this respect, it makes for an interesting comparison with In The Heat Of The Night, which film I also reviewed recently, a film which also includes the n-word in a way to demonstrate its offensiveness, also exposes the evils of racism, and tells of growing respect between an instinctively racist white man and a black outsider.

In TKAM, the black protagonist is an innocent and well-meaning labourer by the name of Tom Robinson (quite beautifully acted with innocent humility and burning injustice by Brock Peters), who is unjustly tried for rape and assault of a young woman (Collin Wilcox) who attempted to seduce the much older Robinson, and was in turn beaten up by her racist father, played with vicious intent by James Anderson. That Robinson is found guilty and dies soon afterwards is a gross injustice, but the form of revenge adopted is the basis of the title and the resolution.

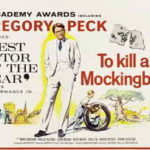

Lee based the character of Atticus Finch on her own father, Amasa Coleman Lee, and must surely have been thrilled at his studied Oscar-winning portrayal by Gregory Peck, the very essence of a logical, rational and above all dignified man facing up to the irrational hatred of racists who care nothing for truth but only that whites are seen to be believed and blacks kept in their place.

The antagonists do not seek justice but expect Finch, the lawyer defending Robinson, to reinforce stereotypes and maintain white supremacy. The greatest thing that can be said of Finch is that he looks his opponents in the eye unapologetically and without fear, in the interests of justice. He stands squarely behind his principles of fairness and respect for all comers.

Perhaps his weakest moment is the speech he makes in court in defence of Tom Robinson, other than to say there is no case to answer. He steers clear of blaming the father, but fails to rip the prosecution case to shreds and remind the jury that their sole responsibility is to determine if the prosecution case has be proven beyond all reasonable doubt, and if not then to acquit. Instead, Finch reasons with the jurors, appeals to their better judgement – but the answer is that they have no shame and no compunction about ignoring the evidence. Who knows? Maybe the other approach would have worked better, maybe nothing he said would have made the slightest difference.

But Finch is the man he is, for better or worse, and a fine man too – the sort of single father any child would be proud to have, engendering human values in his children. He is aided at home only by housekeeper Calpurnia (Estelle Evans) – a name chosen deliberately by Lee (the original Calpurnia being wife of Julius Caesar, who had a premonition about his assassination.)

But this makes TKAMB sound like something that it is not, for the bulk of the action relates to the children and, paradoxically, how their naivety shames the older people who should know better. Scout greets Mr Cunningham as he pays part of his legal bill in hickory nuts, and then reminds him of the fact as Atticus faces up to the vigilante gang at after Tom’s blood the jail house, shaming the entire gang into submission: children have that power.

For the most part the children (Scout, elder brother Jim and neighbour’s son Dill (John Megna), apparently modelled on her childhood friend Truman Capote) play and experience the world. For example: adult attitudes are a complete mystery to children; they experience a mad dog, shot by Atticus with a .22 rifle; and the myths propagated against the shy, misunderstood recluse Boo Radley (a very young and entirely silent Robert Duvall), who turns out to be a very different kettle of fish, a hero in his own right.

Ultimately, it is Radley coming to the defence of Jim and Scout that make this the story it is, counterpoint to the injustice weighed on Robinson, and the loss of childhood innocence, though what stands out for me is how adults patronise children, something Atticus largely succeeds in avoiding (allowing for ticking off Scout about fighting at school.)

What I like most is the effect of returning to this film a year or more after I last saw it. For one thing, the restored B&W HD format makes Mockingbird look quite breathtakingly beautiful and more detailed than you ever remember it. It is at all levels a beautiful film, rightly elevated to the Library of Congress for being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” – and placed in the AFI’s top 100 list (34 in 1998, rising to 25 in the 2007 rankings.) As time goes by and memories mature, the importance of this film becomes all the more critical.