“One final thing I have to do… and then I’ll be free of the past”

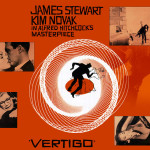

Hitch is renowned as the “Master of Suspense” and the 1958 thriller Vertigo is known as one of his greatest movies, to the extent that it was voted as the greatest film of all time in the BFI Sight and Sound critic’s poll in 2012, replacing the mighty Citizen Kane. I doubt if even Hitch would have accorded his movie this honour, but even with revisionist hindsight that is a fairly momentous choice, not one that happens by accident.

Why would a 1958 psychological thriller about identity, deceit and obsession be accorded such an accolade? Two common hypotheses may each have a tale to tell: one is that this was, for Hitch, a more personal film, telling of his obsession with blonde actresses; the other is that this is a movie with greater depth and ambiguity than almost any other Hitchcock movie – though continuing further along the same path trodden in Spellbound. At face value Vertigo might seem cut and dried, but it is unquestionably a movie that repays deeper psychological analysis; the more you look, the greater the uncertainty. It reminds me of singer Don McLean being asked what his most famous song American Pie means, to which he replied, “it means I never have to work again.”

Reviews and re-evaluations add spice to this debate every few years. Roger Ebert gives a glowing analysis (see here) and this review in the Guardian gives much food for thought. There are no definitive answers, and that adds to the fascination. The key questions might include these:

- Forgetting the secret plot, is there any reality in a person becoming obsessed or possessed by another person, dead or alive?

- Could guilt induce an unresponsive catatonic state for months on end?

- What drives a man to change a woman try to recreate the one he loved and lost?

- Could a woman really act so convincingly that she was not the same woman without him realising?

- Could acrophobia/vertigo be cured by psychological confrontation of the situation inducing fear?

- …and many more. I suspect a psychologist would have a field day with this material.

On a purely technical level, Hitch was always well ahead of the competition. For 1958 Vertigo was, as were many of his movies, a bold technical tour-de-force, even if the spiral effects and the dolly-zoom height shots that gave people motion sickness are gimmicky. The dream sequence, including animation and “falling” shots looks slightly cheesy now but invoked fear at the time, just as Hitch envisaged.

Even if you disregard these scenes, the movie looks absolutely ravishing since the excellent restoration of the original film stock allowed us to see the glorious VistaVision colours as they were intended, and sounds equally vibrant since Bernard Herrmann‘s sympathetic and romantic score were added from the original recordings, but more to the point it is the rich human psychology in the drama that sustains interest.

The visuals, rich in greens and reds, are definitely striking, including many locations around San Francisco – most notably the famous scene at the base of the Golden Gate bridge in which “Madeleine” apparently tries to drown herself while in a trance, only to be saved by Scottie. Most famously of all, the old Spanish San Juan Bautista Mission, roughly 100 miles south of Frisco, makes an iconic location for the climactic moments of the film – though the famous bell tower actually burned down and was therefore recreated in the studio by Hitchcock’s team. Wikipedia:

The mission and its grounds were featured prominently in the 1958 Alfred Hitchcock film Vertigo. Associate producer Herbert Coleman’s daughter Judy Lanini suggested the mission to Hitchcock as a filming location. A steeple, added sometime after the mission’s original construction and secularization, had been demolished following a fire, so Hitchcock added a bell tower using scale models, matte paintings, and trick photography at the Paramount studio in Los Angeles. The tower does not resemble the original steeple. The tower’s staircase was assembled inside a studio. The mission includes a cemetery, with the remains of over 4,000 Native American converts and Europeans buried there

The storyline has been described as: “boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy meets girl again, boy loses girl again,” though the gain ultimately is that John “Scottie” Ferguson (James Stewart) loses the acrophobia (fear of heights) and vertigo (a sensation of dizziness and spinning) that had plagued him since an accident in which he nearly died and the cop who tried to save him plummeted to his death.

Two women sacrificed for Scottie’s well-being might seem harsh, but he could always turn to the delightful Midge (Barbara Bel Geddes, later Miss Ellie in Dallas) who loves him devotedly. No doubt after the closing titles Scottie ends up married to Midge and the guilty party is apprehended from his cruise on the Mediterranean. Maybe they all live happily ever after – though being a Hitchcockian story, probably not. Hitch famously treated his actors like cattle and tortured them by any means available.

In fact, Hitch’s source material was a free adaptation of a French novel, D’entre les morts by two writers known collectively as Boileau-Narcejac. But, being Hitch and ever the perfectionist, the story was processed for a year and then a succession of three writers employed before it was turned into a product he deemed good enough for the screen. For example, he chose not to save the denouement until the end, but to reveal the truth two thirds of the way through. Only Hitch could get away with that without spoiling the tension, but then he was the master.

The care spent in the meticulous planning of script and production alike reaps dividends. For one thing the script plays to the strengths of the cast, notably a touch of knockabout humour to suit the warm-hearted everyman that was Jimmy Stewart, but also very precise language that conjures many images. But the script only takes you so far, for in Hitchcock’s mode of ratcheting up the tension, every look, every gesture, every nuance plays a part.

One of the most effective scenes in the film is conducted in total silence as Scottie follows “Madeleine” around San Francisco on the false trail planted by Tom Helmore‘s Gavin Estler. The effect is eerie, certainly creating the mood that Madeleine, in contrast to Midge and indeed to Judy in the later scenes, is cold, aloof, detached, oblivious to all around her. The “cold” role seems strangely out of character for Kim Novak, and indeed she was very much second choice after Vera Miles “fell” pregnant (as they say) and pulled out of the picture.

Scottie knows something is wrong without being able to put a finger on it. The tables are turned when after Madeleine’s apparent death he haunts the same locations and sees Madeleine in women who, on closer inspection, look nothing like her – until, of course, he sees a woman who is the same woman – and then he has to change her to look like the Madeleine of his memories. You wonder whether Miles would have been any less a mannequin for Hitch’s orders as Novak, or whether she might impose more personality into the role, but I suspect he was pulling the strings deliberately to create a sense of unease in the actress and the audience – and boy, did he succeed. Just as the women in the film are objects of desire, to be manipulated, so were leading ladies to Hitch.

My view of Vertigo, having seen it many times, is that after all this time it remains a movie of fascination, certainly worthy of its place among my “classics” selection. But there’s one thing I really need to know, something that’s been bugging me for years: at the beginning Scottie slips and falls while chasing a suspect, and is hanging on to a plastic gutter for all he is worth. The only policeman with him slips and falls to his death. There is nobody else about, the gutter looks flimsy and Scottie is about to fall any second… then Hitch cuts to the next scene. How did Scottie escape, unless the criminal returned to give him a hand? I guess we will never know…