The broad-backed hippopotamus

Rests on his belly in the mud;

Although he seems so firm to us

He is merely flesh and blood.

T S Eliot

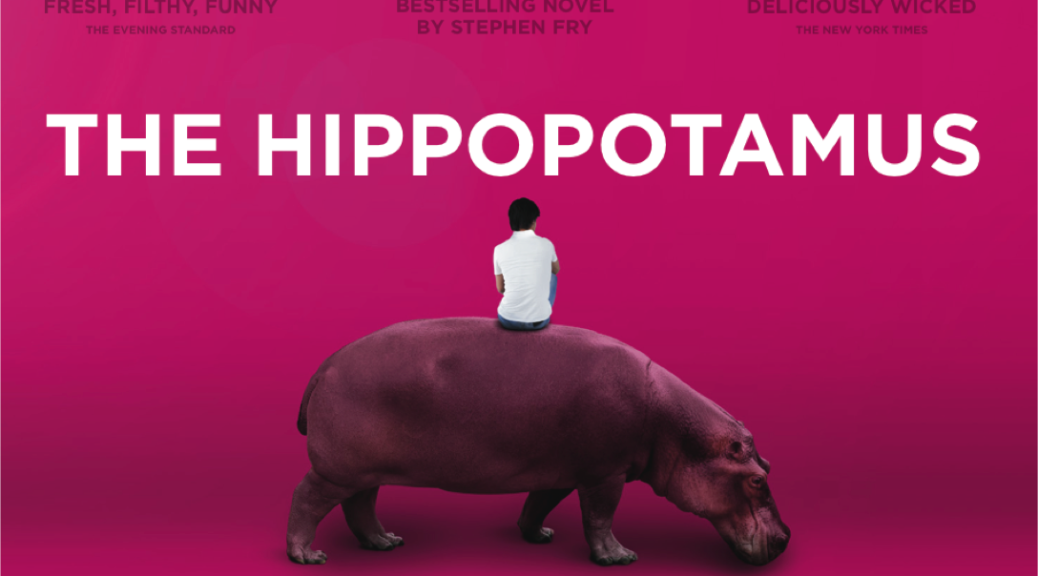

The biggest problem with The Hippopotamus is that there are no hippopotami therein, once you discount the sight of the leading protagonist in the bath. Maybe Hippopotamidae would improve the film? No, I’m not serious.

Any movie based on a Stephen Fry novel can’t be all bad, though I reckon many British viewers, and critics too, seem to have found ample reason not to like this adaptation. Americans might well chortle into their boots at the quintessential Britishness of The Hippopotamus.

There is also the customary English country mansion, smart young woman, aristocratic nonsense aplenty, all the stuff of the ennui of the moneyed classes. You could easily regard it as latter-day Waugh, complete with overtones of disreputability, were it not for the inherently modern language and technology. More than this, and the clever Fry-like ability to construct from mere words epigrams worthy of Wilde.

They don’t come more quintessentially Britishly Fry-like than the mellifluous Roger Allam in the persona of pompous, bombastic, sweary and cynical whisky-soused ex-poet and critic Ted Wallace, the eponymous hippopotamus. Wallace is a character whose only ambition appears at first sight to be to offend everyone while drinking himself to death. He it is who is the primary mouthpiece for Fry’s verbal dexterity, which makes him inherently literary rather than real, though you can’t blame Allam for that.

For the other primary ingredient, Fry gives us a thorough analysis and refutation of the anecdotal nature of miracles. Yes, you read correctly.

Wallace, having disgraced himself in public one too many times, is commissioned by Emily Berrington‘s Jane Swann, a beautiful young woman apparently dying of leukaemia, to investigate the presence or otherwise of miracles at Swafford Hall in Norfolk.

Swafford is home of Wallace’s ex-friend Lord Logan (Matthew Modine emulating Waugh’s Lord Copper as an American baronet), his wife and one-time conquest Anne (Fiona Shaw), their two sons (Wallace’s godsons Simon and David), assorted larger-than-life hangers-on (look out in particular for Tim McInnery‘s outrageously camp judge Oliver Mills) and staff.

This might sound a straightforward task, though with the household divided between believers and non-believers it is asking much of the embittered alcoholic, yet somehow Wallace eventually rises to the task, albeit after a number of bizarre and risqué comic moments on which I won’t elaborate, other than to say this is not a film to watch if you are easily offended.

“Fresh, filthy, funny,” cried the Evening Standard, and you could not disagree – though the consensus view is that the film is worth round about 2-3 stars out of five (45% says Rotten Tomatoes), suggesting that the film and its script is way too far up its own rear end and relying too far on shock tactics to gain laughs. I suspect there is also a degree of discomfiture with the whole concept. One commenter says this:

Despite a wonderfully witty voiceover and the bullish playing of a willing ensemble, this bawdy romp consistently stumbles over its more contrived excesses.

Another adds:

This British satirical comedy may be a bit of a mess, but since it’s based on a Stephen Fry novel, the snappy wit in the dialogue zings with his specific brand of intelligent humour.

The bottom line is this: if you like Stephen Fry, chances are you will like this adaptation of his novel. If you consider him boorish and self-serving, you almost certainly won’t enjoy it.

That said, strip away the veneer of aristocracy and near-the-knuckle humour and you have a serious point. More could and should be made of it, though the ending of the film, as with the book, is at least slightly satisfying, despite a funeral. If Fry’s alter ego Wallace can begin writing poetry after 30 years, there is hope for all of us!