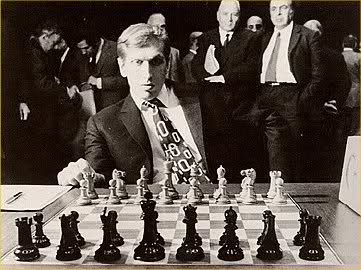

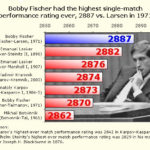

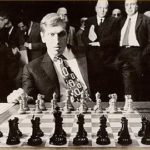

Another day, another remarkable documentary. This one reveals a lot about the about the life of one time World Chess Champion and prize eccentric Bobby Fischer, and celebrates his achievements. Truly an eventful life, even if much of it was lived as a recluse. Greatest chess player of all time? Maybe so – he appears to have achieved the highest ever rating, and the interviewees here certainly think he was truly great at his best.

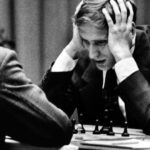

However, while the dark flip side of Fischer is disused at length through this film, I don’t think it ever comes close to understanding the inner workings of the man or why he imploded – other than to spot a trend of other chess-playing geniuses succumbing to mental illness, and noting that losing was simply not a possibility to Fischer – his ego could not withstand such doubt, the presumed reason why he lost his title rather than face the next Soviet challenger, Anatoly Karpov.

Can it explain his weird dalliances with religion? No. Can it explain why a man with Jewish parents should turn so violently towards antisemitism? No. Nor that he gradually became a gibbering and paranoid wreck of a man in the second half of his life, culminating in exile in Iceland and refusing dialysis to prolong his life. Genius is indeed a very strange phenomenon, a hair’s breadth from madness.

The film falls into three sections: up to the 1972 World Championship Final, where Fischer earned the right to challenge the very decent and sporting Champion Boris Spassky, the match itself, and his gradual decline thereafter. It incorporates interviews with chess players Anthony Saidy, Larry Evans, Sam Sloan, Susan Polgar, Garry Kasparov, Asa Hoffmann, Friðrik Ólafsson, Lothar Schmid and others, and includes rare archive footage from the 72 Final (if you are interested in reading more, the book Bobby Fischer Goes To War by David Edmonds and John Eidinow tells it in glorious detail.)

It records Fischer’s childhood with mother Regina, from whom he was later estranged, his discovery that the man he knew only as his mother’s friend and who later died was in fact his father (maybe Bobby did not forgive him for dying?) But especially it records his obsession with chess from the age of 6, rising to become a self-taught Grandmaster at the astonishing age of 15, beating many senior GMs in the process.

From that point ascent to World Champion seemed a formality, though even in those days paranoia seemed to afflict Fischer. He accused the Soviet Union of planting bugs and even trying to poison him. On several occasions he made impossible demands of the organisers, sometimes failed to turn up or walked out if his demands were not met. At least in part, most commentators consider his action mind games to unsettle his opponents, and there’s no doubt that they succeeded too.

In the 72 Final Fischer arrived very late for the first game, then demanded TV cameras be removed. He failed to turn up at all for the second game, then demanded the match be played in a private room. He argued about prize money and more besides. From Wikipedia:

For some time, it was doubtful that the match would be played at all. Shortly before the match, Fischer demanded that the players receive, in addition to the agreed-upon prize fund of $125,000 (5/8 to the winner, 3/8 to the loser) and 30% of the proceeds from television and film rights, 30% of the box-office receipts. He failed to arrive in Iceland for the opening ceremony on July 1. Fischer’s behavior was seemingly full of contradictions, as it had been throughout his career. He finally flew to Iceland and agreed to play after a two-day postponement of the match by FIDE President Max Euwe, a surprise doubling of the prize fund by British investment banker Jim Slater, and much persuasion, including a phone call by Henry Kissinger to Fischer. Many commentators, particularly from the USSR, have suggested that all this (and his continuing demands and unreasonableness) was part of Fischer’s plan to “psych out” Spassky. Fischer’s supporters say that winning the World Championship was the mission of his life, that he simply wanted the setting to be perfect for it when he took the stage, and that his behavior was the same as it had always been.

Whatever the reasons, even allowing for a bad mistake in game 1 and conceding game 2, Fischer ground down Spassky with some brilliant and innovative play to become the World Champion. In an interview he said he would now play more chess, though in practice his public displays reduced and the eccentricity increased.

Indeed, the only other public match in which Fischer participated was a rematch against Spassky and billed as the “unofficial world championship.” It was staged in 1992 in the then Yugoslavia – resulting in an arrest warrant due to American sanctions against the country due to the ongoing wars and ethnic cleansing.

Naive maybe, but more damning was the description by experts that this was a match staged between two men way past their best – “rather like the sight of two former heavyweight boxers, well past their prime climbing back into the ring for a last big payday..” Worse still, one is quoted in the film as saying this was 1972 chess; the game had moved on, and the dinosaurs had not moved with it.

Fischer became more like a hermit. Edmonds notes that “sightings of him became as rare and often no more accurate than those of the Loch Ness monster,” though this film offers no real insight about Fischer or how he occupied his time during the many long years of his exile. It is known where he lived (eg. for some years in Hungary, ending when it became apparent that his companion, Hungarian chess prodigy Zita Rajcsanyi, would not marry him), though Fischer led a nomadic existence, almost walking the earth in search of something, maybe even he did not know what?

One thing I would have loved to be added to this film would be a psychological or even psychiatric profile of a man with genius IQ, a lack of social skills and a very troubled existence. Sadly, since Fischer died in 2008 we are never likely to obtain more than a theoretical analysis from the clues available, but somehow I wish there was something more to get deeper inside the man’s head.

My advice: enjoy the film for what it is, then form your own opinions about this most enigmatic of characters.