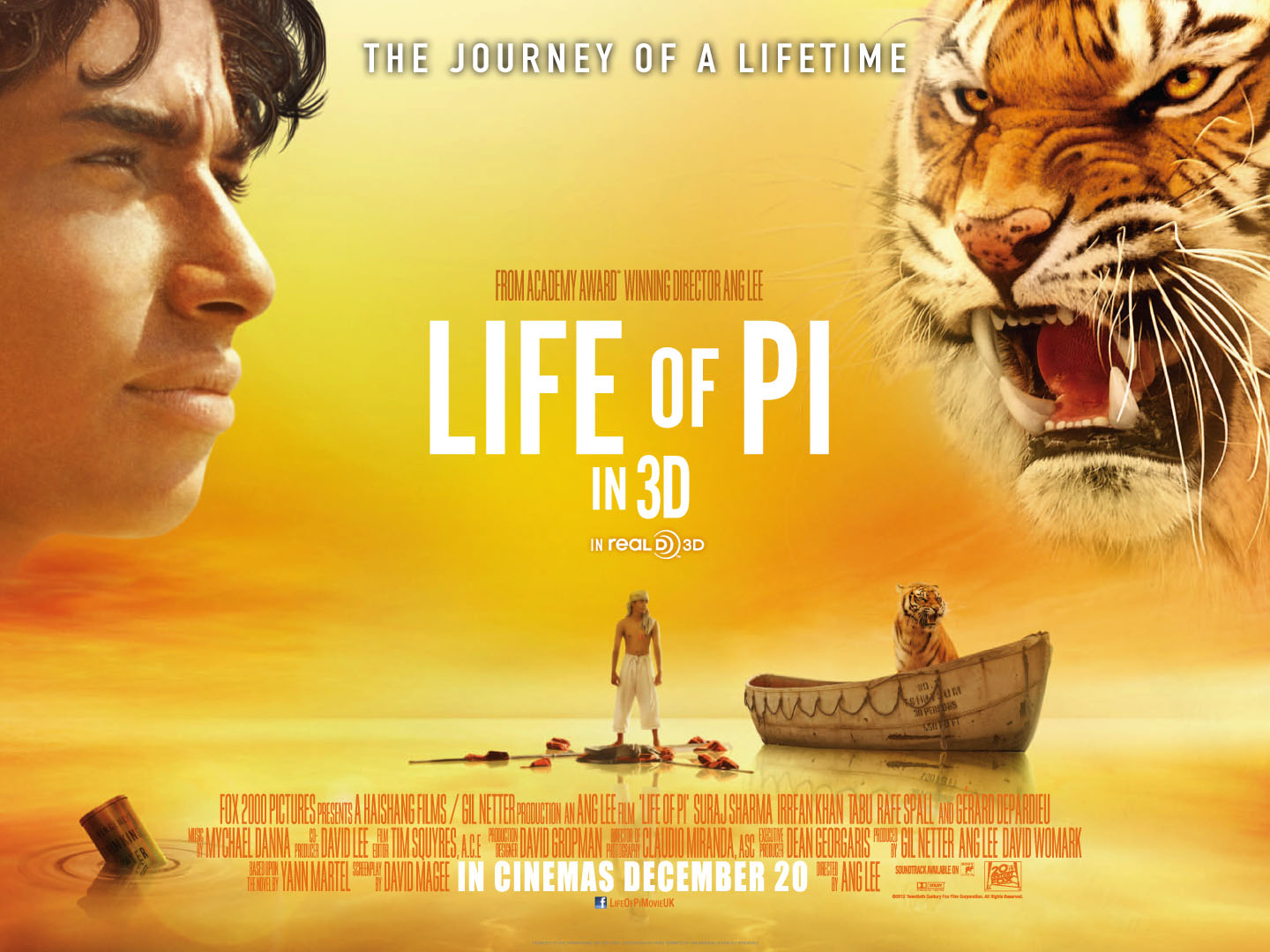

Life of Pi is two movies in one: one is a wily allegorical tale told retrospectively by the adult Piscine Molitor “Pi” Patel to a Canadian novelist by the name of Yann Martel, who just happens to be the writer of the Booker prize-winning novel Life of Pi; the second is a technical tour-de-force told by the techies who created the most amazing CGI effects in order to realise said novel and render it to the big screen under the stewardship of Oscar-winning director Ang Lee.

The former is a deceptively simple story focusing on the relativity of truth and with pan-religious agenda. While the tale opens with the life of Pi with his family in French-speaking Pondicherry in India, the biggest proportion of screen time is shared between the 16-year old Patel and a Bengal tiger by the name of Richard Parker (taken from the name of a character in an Edgar Allen Poe story) in a lifeboat somewhere over the Pacific. But I shall return to the storyline anon…

It’s fair to say that what you can’t ignore about this movie is the beauty of its visuals, and doubtless they look better still in 3D. Even on 2D DVD it looks stupendously ravishing, which is entirely credit to the special effects gurus who have created the environment almost from scratch. A few real actors apart, there is a boat in a tank, a makeshift deck from the freighter on a gimbal, plus studio interiors and location shots in India, but (a brief appearance from a hyena playing the part of Harry the Hyena notwithstanding), the animals and fish are all virtual (sorry, there were a few rubber flying fish too!) Most of the waves are virtual, the island is virtual, pretty much everything requires the talented young Indian actor Suraj Sharma to pretend he is performing with a real tiger, scarcely the easiest of accomplishments. Note for future reference: never work with animals (real or otherwise), children or animations.

The art has clearly moved on a long way since Ray Harryhausen‘s legendary stop-motion special effects in Jason and the Argonauts; all the CGI characters look not only realistic but also express emotion realistically – arguably more so than some actors one could name! Apart from odd occasions when the mask slips and the artifice of CGI is exposed – which is, in a way, reassuring – the whole thing looks beautifully naturalistic and a glorious backdrop for what is essentially a simple and elegiac tale, not an all-action blockbuster movie, guns ablaze. This is not just a case of special effects, of course: cinematography by Director of Photography Claudio Miranda won him a well-deserved Oscar.

So then, full marks for appearance, but what about content? I can imagine that those who think not much happens in Gravity would think much the same about Life of Pi. The two share several parallels, not least the art of survival under extreme conditions. But where Gravity is a study of the here and now in real time, albeit in space, this is, like Big Fish, Amadeus and many more films, the use of an unreliable memoir to tell a tale in flashback. In fact, we get two versions of what happened, one with animals and one, verbally but not visually, substituting members of the crew for the zebra, hyena, orang-utan and tiger – seen through by the author’s alter ego in the telling – each representing behavioural characteristics that suit the allegory.

But the point allegedly being made here being that Pi savours the ambiguity in order to make a point about the nature of religion. He asks Martel which story he prefers, to which the writer replies the one with the animals; Pi replies: “Thank you. And so it goes with God.” In other words, the stories have purpose when being told to demonstrate the presence and role of a deity, something I would dispute but which suits the story.

Worth noting then the explanation of themes in the book, as noted in Wikipedia:

Life of Pi, according to Yann Martel, can be summarized in three statements- “Life is a story… You can choose your story… A story with God is the better story.” A recurring theme throughout the novel seems to be believability. Pi at the end of the book asks the two investigators “If you stumble about believability, what are you living for?” According to Gordon Houser there are two main themes of the book: “that all life is interdependent, and that we live and breathe via belief.”

In view of its hero flirting with Hinduism, Christianity and Islam, you might believe that this is cod theology on the essence of spirituality. No doubt purists in each tradition would be cursing Martel and Lee in equal measure, though I suspect that Martel’s response would be along the lines that “you’re missing the point.”

However, this is not the only tale. The strangely symbiotic relationship between boy and tiger ends when, at the dangerous island that turns carnivorous by night and consumes unwary prey, the tiger vanishes deep into the jungle without a second glance, leaving Pi feeling crushed. If you accept the second version of events, whereby Richard Parker is actually Pi, you can ask what significance there is in Pi trying to tame the wilder side of his own nature but ultimately failing to curb his wilder excesses. As further noted on Wikipedia:

PBS has described Martel’s story as one of “personal growth through adversity.” The main character learns that “tigers are dangerous” at a young age when his father forces him to watch the zoo’s Royal Bengal tiger patriarch, Mahisha, devour a live goat. Later, after he has been reduced to eking out a desperate existence on the lifeboat with the company of a fully grown tiger, Pi develops “alpha” qualities as he musters the strength, will and skills he needs to survive.

The goat story never makes it to the movie, but the survival theme and the parallels with the tiger are easy to spot.

A friend reminds me that there are also darker themes:

But what of the many unspeakable subtexts? Cannibalism, oedipus complex , voyeurism? The very dark side of The Life of Pi is kind of what makes it such a great work of literature and film including the references to Edgar Allan Poe via the tiger Richard Parker. It explores what it is to be human and the similarities and contradictions of religions when faced with the most basic instinct of all, survival. I think it is possible to see the film and take it at face value, albeit with some questions maybe. I think the way the island is presented visually and via Guatam Belur’s acting is very sexual and weighted with references to the unspeakable, namely, that he has had to consume the dead body of his mother. The character of the interviewer, Yann Martel, of whom we know nothing except he is the witness to this story recounted to him by Pi, is very interesting as it seems he is us, the listener, viewer, the voyeur and we are deliberately left in the dark about his motives and opinions, just as the director also makes no inference about morality. Like Yann we are left to make of this what we will and judge or not

Whether or not you agree with the thrust of Life of Pi‘s mild lesson in philosophy and theology, you could equally take it at face value and enjoy the work for its aesthetics and gentle narrative. For a reviewers purpose, it tells its story well, without losing narrative drive in spite of the long period when a boy and a tiger in a boat dominate proceedings. For that mercy, many congratulations to Mr Lee – and his army of technicians – on a job very well done.