In my Movies That Make Me Cry blog, I wrote the following:

Lost in Translation: that scene at the end when they finally hug and he whispers in her ear. She nods. We never know what they have said, but this is one occasion when we can let our imaginations run riot. It is a beautiful moment.

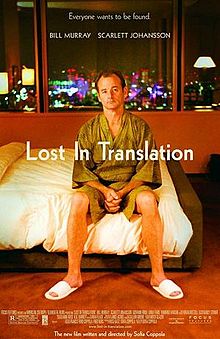

But this is just one of very many reasons to watch and enjoy this movie. Most of my favourite movies were made before 1975. Sofia Coppola‘s second feature as a director, Lost in Translation, was made in 2003, but arguably employs many of the timeless virtues that make movies worth watching.

The first of these is to underwrite the piece and allow the actors to develop both rounded characters, credible relationships and emotional complexity without the encumbrance of doing and saying things unnecessarily. Like Brief Encounter it portrays a chaste bittersweet, almost entirely unspoken romance in which two people know precisely what is going on but barely articulate any emotion between them. Non-verbal acting is entirely used to indicate the depth of feeling. It’s all in the eyes, the body language, the intensity of feeling. And yes, it does move me to tears.

What puts many people off LIT is that nothing really happens. Except, of course, it does, subtly and largely without words. Perhaps we all expect to be spoonfed plots these days, but here the story evolves around two people thrown together by two common factors: insomnia and loneliness.

The movie has been described as a study of loneliness, alienation, ennui, the culture shock of westerners in Tokyo, and, ultimately, of an unconsummated love between two people who have only their insomnia and nationality in common. In fact, it’s also very funny, helped greatly by improvised sections with the actors playing along with Japanese extras without either understanding a word the other speaks.

While the plotting may be minimal, the acting is sublime. Bill Murray, he of the deadpan face worthy of the late Leslie Nielsen, is just brilliant at every level, particularly in reacting to the confusions of Japanese life, culture and people, but as an unlikely romantic hero too. He has mastered the art of conveying moods with the most subtle shifts of facial muscles, and uses this skill to glorious effect. You don’t need him to explain, his look says everything with an economy of effort worthy of the best.

Murray’s Bob Harris is an American movie star in Japan to make a commercial for a Japanese whisky manufacturer. Harris is a fish out of water but in spite of his eternal insomnia relishes the freedom, albeit he cannot escape an endless series of faxes from his wife back home in the USA. He is dissatisfied but goes through the motions, the money is scant consolation and the reminders of home something he could well do without. He is empty as a paper bag before meeting Charlotte, and emptier still upon leaving her.

Scarlett Johansson, a mere 18 when the movie was made (and who incidentally shares the same birthday as me!), matches Murray, 34 years her senior, every step of the way. She plays Charlotte the bored wife of photographer on a photo shoot in Japan and paying her no attention at all.

When they are together, he sleeps and she contemplates the loneliness of her life, gradually forming a late-night liaison with Harris in the cabaret bar and then beyond, finding company and ways to entertain one another with simple, human feeling. Johansson plays the role with a maturity beyond her years in conveying the inner emptiness she shares with Harris, and how the relationship brings something her marriage cannot provide.

While the pair explore Japan apart and together, the bright lights and the quiet history, their chaste bond grows to the point of jealousy and mutual dependency. It reaches a climax as Harris stops his taxi on the way to the airport, chases after Charlotte and engages her in a warm embrace dripping with emotion.

He speaks words in her ear, she nods, he leaves Japan for good. We cannot hear what he says, we can only speculate. This moment of ambiguity is sheer cinematic magic. A moment of total beauty, to be cherished. This is ultimately what makes a damn good film, a warm, funny and enchanting picture into a great movie.

And we can only imagine whether they ever meet again, and if so what will happen. Will they choose to have a mad affair, one doomed to failure? Will they just be friends but exchange on occasions a knowing glance, a memory of that time together in Tokyo and the shiver that passed down their respective spines? My daughter thinks they will never meet again and that Bob was only reassuring Charlotte… but you never know.

A great movie is one that inspires your imagination… it’s always far better for any director to let the audience join the dots in their own minds than spelling it all out. And this is, to my mind, a great film. It’s budget, by the way, was $4m, evidence that you don’t need massive money to create a timeless movie.