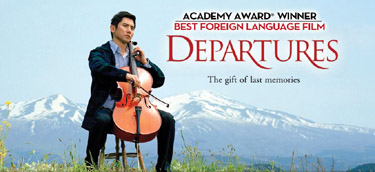

Modern Japanese cinema has never exactly been mainstream over here, but it contains some true gems that stand on their own merits rather than just as cultural oddities. Readers will know I greatly enjoyed Tampopo, the Japanese spoof western concerned mostly with the themes of sex and food, but Yōjirō Takita‘s Departures is quite different.

It is an elegiac movie, not without humour but mostly dedicated to the beauty of the moment. The moments in question include the beauty of music played on the cello, but mostly the preparation of bodies for funeral in the Japanese tradition (see quote from Wikipedia below), the art of the undertakers and the reactions of the bereaved, mirrored in the snowy Japanese landscapes featured in the breathtaking cinematography of Takeshi Hamada.

In so doing, it examines with delicate touch the nature of grief and the taboos surrounding death, even in a country where preparation of the dead in front of mourners is the norm. First and foremost this is a character study of the living, those coping with death in their respective capacities, but also how death is the fate of the living.

Woven around these moments is the life of Daigo Kobayashi (Masahiro Motoki), at one time a cellist who loses his job and looks for a fresh challenge. Following an ad for an acting job, he finds himself working for an undertaker, for which a strong stomach is sometimes required. This career choice is later found to be contrary to the wishes of his wife Miko (Ryōko Hirosue), from whom he hid the nature of his new career. It is her words, “you’re unclean” that ring loud and clear about society’s taboos.

Rather than adding to this, I strongly recommend reading the Wikipedia page for this film, linked above. It will tell you far more than bears repeating here, though I do agree with Roger Ebert’s assessment when he described the film as “rock-solid in its fundamentals.”

Japanese funerals are highly ritualized affairs which are generally—though not always—conducted in accordance with Buddhist rites.[2] In preparation for the funeral, the body is washed and the orifices are blocked with cotton or gauze. The encoffining ritual (called nōkan), as depicted in Departures, is rarely performed, and even then only in rural areas.[3] This ceremony is not standardized, but generally involves professional morticians (納棺師 nōkanshi?)[b] ritually preparing the body, dressing the dead in white, and sometimes applying make-up. The body is then put on dry ice in a casket, along with personal possessions and items necessary for the trip to the afterlife.[4]

Despite the importance of death rituals, in traditional Japanese culture the subject is considered unclean as everything related to death is thought to be a source of kegare (defilement). After coming into contact with the dead, individuals must cleanse themselves through purifying rituals.[5] People who work closely with the dead, such as morticians, are thus considered unclean, and during the feudal era those whose work was related to death became burakumin (untouchables), forced to live in their own hamlets and discriminated against by wider society. Despite a cultural shift since the Meiji Restoration of 1868, the stigma of death still has considerable force within Japanese society, and discrimination against the untouchables has continued.[c][6]

Until 1972, most deaths were dealt with by families, funeral homes, or nōkanshi. As of 2014, about 80% of deaths occur in hospitals, and preparation of the bodies is frequently done by hospital staff; in such cases, the family often does not see the body until the funeral.[7] A 1998 survey found that 29.5% of the Japanese population believed in an afterlife, and a further 40% wanted to believe; belief was highest among the young. Belief in the existence of a soul (54%) and a connection between the worlds of the living and the dead (64.9%) was likewise common.[8]