Stanley Kubrick, remarkable director that he was, did not make many films, but those he did were given obsessive attention to detail and both time and space in which to develop to the fullest extent of cinematic capabilities, of which 2001 is arguably the prime example. That was his science fiction movie; Full Metal Jacket was his Vietnam movie, though he did make Paths of Glory was an earlier war movie; Dr Strangelove his nuclear satire; Barry Lyndon was his historical drama; and A Clockwork Orange was his take on Burgess’s analysis of violence and the state.

The Shining was his horror film, adapted from Stephen King‘s novel of the same name. I saw it for the first time in the USA in 1980, several more times since, and now on DVD because the legend of The Shining had finally reached my 16-year old son. It’s the sort of movie people talk about, and let’s face it – creating a buzz is what hordes of highly-paid movie executives would kill for when they try to flog their products to the cinema going public.

In many ways it is a conventional and formulaic horror, typical in plot of the horror pics that are cynically churned out by the hundred, though it has spawned its own generation of me-too plagiarisers. What differentiates this from all other films in the same category is the lengths to which the director would go to get exactly the right effects, and to induce performances that went way beyond the normal limitations of screen acting. In that respect he was very like Hitchcock, who was legendary as the master of suspense but also for treating actors like cattle. In the case of Shelley Duvall, the impact of Kubrick’s maltreatment was to induce stress and very genuine fear – and boy, does she look terrified! From Wikipedia:

The Shining had a prolonged and arduous production period, often with very long workdays. Principal photography took over a year to complete, due to Kubrick’s highly methodical nature. Actress Shelley Duvall did not get along well with Kubrick, frequently arguing with him on set about lines in the script, her acting techniques and numerous other things. Duvall eventually became so overwhelmed by the stress of her role that she became physically ill for months. At one point she was under so much stress that her hair began to fall out.

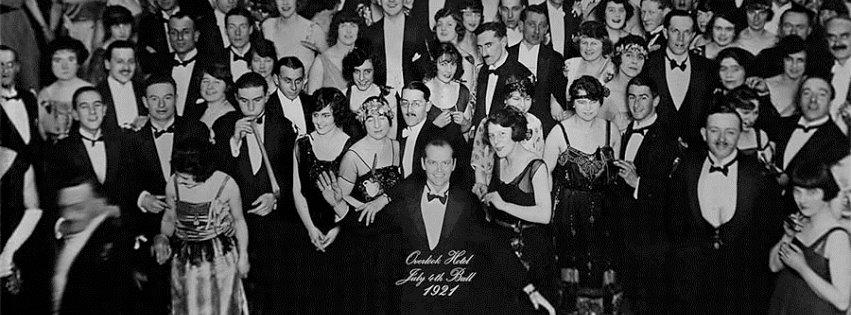

Jack Nicholson, meanwhile, had his own frustrations (see below), though the impact was to transform his performance into something truly iconic and charismatic – you can’t take your eyes off him, though in hindsight he probably looks way over the top. This movie sees every possible variant of visceral glare that can be extracted from his mobile features, indicative of some weird inner process that sees him transform from the agreeable, if slightly sinister husband and father, via bully into a dark and psychotic maniac, imbued with the spirit of the dead from the Overlook Hotel. This is how his creative tension was ratcheted up:

The shooting script was being changed constantly, sometimes several times a day, adding more stress. Jack Nicholson eventually became so frustrated with the ever-changing script that he would throw away the copies that the production team would give to him to memorize, knowing that it was just going to change anyway. He learned most of his lines just minutes before filming them. Nicholson was living in London with his then-girlfriend Anjelica Huston and her younger sister, Allegra, who testified to his long shooting days.

The story of how Kubrick innovated with the Steadycam also bears repetition, and like Hitch he understood the technical detail behind the art of cinematography, having graduated from shooting pictures himself. This was typical of how he applied and adapted the technology to achieve a very specific effect:

This film was among the first half-dozen to use the newly developed Steadicam (after the 1976 films Bound for Glory, Marathon Man, and Rocky), and was Kubrick’s first use of it.This is a stabilizing mount for a motion picture camera, which mechanically separates the operator’s movement from the camera’s, allowing smooth tracking shots while the operator is moving over an uneven surface. It essentially combines the stabilized steady footage of a regular mount with the fluidity and flexibility of a handheld camera. The inventor of the Steadicam, Garrett Brown, was heavily involved with the production. Brown published an article in American Cinematographerabout his experience, and contributed to the audio commentary on the 2007 DVD release of The Shining. Brown describes his excitement taking his first tour of the sets which offered “further possibilities for the Steadicam”. This tour convinced Brown to become personally involved with the production. Kubrick was not “just talking of stunt shots and staircases”. Rather he would use the Steadicam “as it was intended to be used – as a tool which can help get the lens where it’s wanted in space and time without the classic limitations of the dolly and crane.” Brown used an 18 mm Cooke lens that allowed the Steadicam to pass within an inch of walls and door frames.

The set design for the interior scenes of the Overlook Hotel was modeled in large parts on the Ahwahnee Hotel – seen here is the Ahwahnee’s great lounge which was recreated on the Elstree Studio set as the Colorado Lounge.

The set design for the interior scenes of the Overlook Hotel was modeled in large parts on the Ahwahnee Hotel – seen here is the Ahwahnee’s great lounge which was recreated on the Elstree Studio set as the Colorado Lounge.Kubrick personally aided in modifying the Steadicam’s video transmission technology. Brown states his own abilities to operate the Steadicam were refined by working on Kubrick’s film. On this film, Brown developed a two-handed technique, which enabled him to maintain the camera at one height while panning and tilting the camera. In addition to tracking shots from behind, the Steadicam enabled shooting in constricted rooms without flying out walls, or backing the camera into doors. Brown notes that: “One of the most talked-about shots in the picture is the eerie tracking sequence which follows Danny as he pedals at high speed through corridor after corridor on his plastic Big Wheel tricycle. The soundtrack explodes with noise when the wheel is on wooden flooring and is abruptly silent as it crosses over carpet. We needed to have the lens just a few inches from the floor and to travel rapidly just behind or ahead of the bike.”

This required the Steadicam to be on a special mount modeled on a wheelchair in which the operator sat while pulling a platform with the sound man. The weight of the rig and its occupants proved to be too much for the original tires, however, resulting in a blowout one day that almost caused a serious crash. Solid tires were then mounted on the rig. Kubrick also had a highly accurate speedometer mounted on the rig so as to duplicate the exact tempo of a given shot so that Brown could perform take after identical take. Brown also discusses how the scenes in the hedge maze were shot with a Steadicam.

But the beauty is that to the audience the technical details are as nothing – what matters is their impact on screen. From the opening helicopter shots of St Mary Lake in Montana, what Kubrick brings to the film is a sense of distance, remoteness, all the more so when the hotel is cut off by snow. It is as distant from humanity as the Antarctic crew in The Thing – excepting the telepathic communication between Jack and Wendy Torrance’s son Danny (Danny Lloyd, who does well in a very demanding role for a young actor) and hotel chef Dick Halloran (the legendary Scatman Crothers), known as “shining”, also responsible for Danny’s ability to see ghosts of past murders in the form of visions.

From a dramatic perspective, the murder of Halloran when he travels from Florida on a premonition and arrives by Snowcat seems counterintuitive, the sort of thing Hitch might well have done to confound audience expectations and unsettle us if we felt he was riding to the rescue. Maybe another cut would finish in a very different way?

But in hindsight, without the shock factor of not knowing will happen, my son and friend, neither of whom had seen the movie before, agreed it was not that scary – though son was a trifle spooked at bedtime. That said there is one scene everyone remembers. Like the ending to the original version of Carrie (another Stephen King adaptation), it is shocking if you don’t know what is coming, but knowing the clues you can see it coming. What is perhaps more unsettling are the small glimpses afforded but never pursued, the sort of vignette that makes you wonder which other directions the movie might have taken, and which you had forgotten entirely when you see the movie some years later.

It is, as the blurb states, “a masterpiece of modern horror”, though the modern in question is 1980 (judge from the design of carpets in the hotel) and far from the only interpretation. In 1997 a mini-series was made from the same source material, one that goes in more detail into Torrance’s back story of alcoholism and explosive temper, into the ghosts within the hotel, and into the shining itself. I wonder if the perfectionist within Kubrick might have made a very different film, had he made it in 2014?