A quest for love, light and wisdom, in a world where nothing is what it seems. A malicious serpent. An evil sorcerer who is holding a beautiful princess captive. A dark queen with manipulative motives. And three testing trials of his courage and virtue. What else must Prince Tamino overcome in his quest for love, light and wisdom?

This is The Magic Flute (AKA die Zauberflöte – synopsis at the bottom of this review) as Mozart could never possibly have envisaged it, one in which the words quoted on the ENO website seem to have been taken at face value. Would we find love, light and wisdom? Read on! The ENO website tells us this about the production:

The Magic Flute is one of the greatest and most popular operas ever written. This is a wonderfully theatrical and imaginative staging from Complicite artistic director Simon McBurney where live sound effects and breathtaking animations help bring this captivating tale to life.

Like Shakespeare, this is a work crying out for a vivid reimagining. However, there is a downside to this temptation in that done badly you have all manner of flouncy additions that may or may not add value, but in the process lose the soul of the work. At least the involvement of ENO musical director Mark Wrigglesworth is a guarantee that the integrity of Mozart’s music is sacrosanct and delivered with vivacity and spirit.

McBurney‘s history certainly tells you this is no lightweight reinvention. Where ENO’s La Traviata was stripped back to a bare stage with many drapes, McBurney has thrown the kitchen sink at Magic Flute – though you wouldn’t know that at first sight. In the movie Amadeus the staging of MF was pretty imaginative (see here and here), but here the stage is bare but for a tubular steel framework supporting a wooden platform.

Only later do you see it used for a wide variety of purposes: as a hill, a cliff ledge, a lighting rig, a conference table, a double-decker heaven-and-hell stage, a screen for projections, but then this is a production in which nothing is as it seems – quite appropriately for the raw material, you might think.

Our first sight of the screens, of which there are four in addition to the platform, comes before the action commences. To stage right a crew member with a chalkboard, chalk and a duster provides an imaginative commentary to the overture, relayed on the front screen and culminating in a vision of rocky mountains as a virtual backdrop. Throughout the show the front and rear screens are used to convey colourful and animations, pictures and projections. For example, as we encounter the magical snake it slithers malevolently across the screens at fifty times life-size.

Done badly this could have made for a truly awful hotchpotch of images and dramatic action, but in practice it makes for an engaging and exhilarating spectacle by drawing the audience into its already fantasy world, often combining the two to transform the limitations of the expanded stage (the action continues into the audience, the orchestra pit and the prompt box at stage right.)

Nowhere is this better achieved than in the trials undertaken by Tamino on his journey, where a crackling fire burns all around he and Pamina one minute, and the next they are floating in a pool of virtual water, aided (presumably) by wires. Where Papageno contemplates suicide, the screen is filled with chalk arrows pointing every which way, reminding me of the three routes incorporated into van Gogh‘s Wheat Field With Crows.

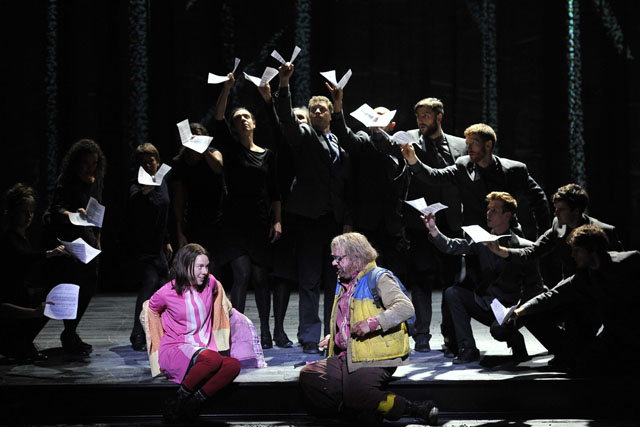

If the aim were to leave the audience gobsmacked, it succeeds admirably – though thankfully not all the effects are virtual. The use of a team dressed in black to create Papageno’s birds, armed with just a sheet of paper apiece, is nothing short of miraculous.

The same level of invention has been applied to every aspect of the show. Costumery is applied with flair and exuberance. The Queen of the Night’s three ladies, like lamia thirsting for Tamino’s blood, entrance him with exotic plumery and a slow striptease into sexy semi-transparent black lace; Pagageno’s bright blue, pink and yellow, making him look (deliberately) like a bearded parrot, are matched by the pink and white finery of Papagena at the end; the three spirits, on the other hand, do a fine impression of Methuselah, at least one foot in the grave but still proffering advice. Elsewhere, fine suits mingle among the long-haired Sarastro’s henchmen, contrasting with the Queen of the Night’s black and Pamina’s pure virginal white.

Colourful it undeniably is, but what of the substance behind the gaudy clothes? A word first on the translation, always a difficult compromise between the emotions of each character and the need for lines to scan. Thankfully they do, though rhyming couplets are occasional rather than the norm. However, this adaptation of Schikaneder‘s libretto makes a virtue of bringing out the absurdist humour, notably the vulgar and lustful Monostatos and lovelorn Papageno, matched by comic mime as the bird man drinks from one bottle of wine and pees into another to get a perfect scale. His forays into the audience, captured on screen for the benefit of we in the Upper Circle, are also good for a giggle.

So what of the acting and singing? Worth saying from the start that Lucy Crow‘s Pamina was truly outstanding. Her rendition of the tragic Pamina’s Lament (as she misinterprets Tamino’s silence as rejection of her) was almost worth the price of admission on its own. Tamino’s tenor, in the form of Allan Clayton, is more than competent, though he will have his work cut out keeping up with his better half. I admired the bass of James Creswell as Sarastro, a commanding and authoritative figure who quells the rage all around him with a laid-back paternal benevolence.

The regular show-stopper in Magic Flute is the Queen of the Night’s Aria, which Ambur Braid‘s soprano delivers with more than a touch of theatricality and the requisite vocal pyrotechnics. However, I truly can’t understand why the queen is terminally frail and wheelchair bound, even if she scoots archly around the stage when seriously affronted. She is after all intended to be the all-powerful face of evil and darkness as well as the mother of Pamina, so I’d have preferred her to demonstrate her powers rather more physically.

As with my recent comments about The Mikado, the fact that the libretto is relayed on the text screen above the the proscenium arch as surtitles is very welcome, though the lack of any such facility for spoken dialogue meant that I missed some of the best lines.

Love, light and wisdom? Well, certainly a bit more than before this magical show, one that I hope revives the flagging fortunes of the ENO. This is an enchanting and entertaining production, all the better since it will give even those who barely give opera an accessible and delightful introduction, though I would warn against applying a technical box of tricks to just any opera. The fact that Magic Flute is, by definition, a fantasy singspiel makes all the difference, but try this approach with Wagner or Verdi or anything dependent on subtlety of emotion and you’d have the potential for a confusing mess.

___

Act 1

Scene 1: A rough, rocky landscape

Tamino, a handsome prince lost in a distant land, is pursued by a serpent and asks the gods to save him (aria: “Zu Hilfe! Zu Hilfe!” segued into trio: “Stirb, Ungeheuer, durch uns’re Macht!“). He faints, and three ladies, attendants of the Queen of the Night, appear and kill the serpent. They find the unconscious prince extremely attractive, and each of them tries to convince the other two to leave. After arguing, they reluctantly decide to leave together.

Tamino wakes up, and is surprised to find himself still alive. Papageno enters dressed as a bird. He describes his life as a bird-catcher, complaining he has no wife or girlfriend (aria: “Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja“). Tamino introduces himself to Papageno, thinking Papageno killed the serpent. Papageno happily takes the credit – claiming he strangled it with his bare hands. The three ladies suddenly reappear and instead of giving him wine, cake and figs, they give him water, a stone and place a padlock over his mouth as a warning not to lie. They give Tamino a portrait of the Queen of the Night’s daughter Pamina, with whom Tamino falls instantly in love (aria: “Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön” / This image is enchantingly beautiful).

The ladies return and tell Tamino that Pamina has been captured by Sarastro, a supposedly evil sorcerer. Tamino vows to rescue Pamina. The Queen of the Night appears and promises Tamino that Pamina will be his if he rescues her from Sarastro (Recitative and aria: “O zittre nicht, mein lieber Sohn” / Oh, tremble not, my dear son!). The Queen leaves and the ladies remove the padlock from Papageno’s mouth with a warning not to lie any more. They give Tamino a magic flute which has the power to change sorrow into joy. They tell Papageno to go with Tamino, and give him (Papageno) magic bells for protection. The ladies introduce three child-spirits, who will guide Tamino and Papageno to Sarastro’s temple. Together Tamino and Papageno set forth (Quintet: “Hm! Hm! Hm! Hm!”).

Scene 2: A room in Sarastro’s palace

Pamina is dragged in by Sarastro’s slaves, apparently having tried to escape. Monostatos, a blackamoor and chief of the slaves, orders the slaves to chain her and leave him alone with her. Papageno, sent ahead by Tamino to help find Pamina, enters (Trio: “Du feines Täubchen, nur herein!“). Monostatos and Papageno are each terrified by the other’s strange appearance and both flee. Papageno returns and announces to Pamina that her mother has sent Tamino to save her. Pamina rejoices to hear that Tamino is in love with her. She offers sympathy and hope to Papageno, who longs for a wife. Together they reflect on the joys and sacred duties of marital love (duet: “Bei Männern welche Liebe fühlen“).

Finale. Scene 3: A grove in front of a temple

The three child-spirits lead Tamino to Sarastro’s temple, promising that if he remains patient, wise and steadfast, he will succeed in rescuing Pamina. Tamino approaches the left-hand entrance and is denied access by voices from within. The same happens when he goes to the entrance on the right. But from the entrance in the middle, an old priest appears and lets Tamino in. (The old priest is referred to as “The Speaker” in the libretto, but his role is a singing role.) He tells Tamino that Sarastro is benevolent, not evil, and that he should not trust the Queen of the Night. He promises that Tamino’s confusion will be lifted when Tamino approaches the temple as a friend. Tamino plays his magic flute. Animals appear and dance, enraptured, to his music. Tamino hears Papageno’s pipes sounding offstage, and hurries off to find him.

Papageno and Pamina enter, searching for Tamino. They are recaptured by Monostatos and his slaves. Papageno plays his magic bells, and Monostatos and his slaves begin to dance, and exit the stage, still dancing, mesmerised by the beauty of the music (aria: “Das klinget so herrlich“). Papageno and Pamina hear the sound of Sarastro’s retinue approaching. Papageno is frightened and asks Pamina what they should say. She answers that they must tell the truth. Sarastro enters, with a crowd of followers.

Pamina falls at Sarastro’s feet and confesses that she tried to escape because Monostatos had forced his attentions on her. Sarastro receives her kindly and assures her that he wishes only for her happiness. But he refuses to return her to her mother, whom he describes as a proud, headstrong woman, and a bad influence on those around her. Pamina, he says, must be guided by a man.

Monostatos brings in Tamino. The two lovers see one another for the first time and embrace, causing indignation among Sarastro’s followers. Monostatos tells Sarastro that he caught Papageno and Pamina trying to escape, and demands a reward. Sarastro, however, punishes Monostatos for his lustful behaviour toward Pamina, and sends him away. He announces that Tamino must undergo trials of wisdom in order to become worthy as Pamina’s husband. The priests declare that virtue and righteousness will sanctify life and make mortals like gods (“Wenn Tugend und Gerechtigkeit“).

Act 2

Scene 1: A grove of palms

The council of priests of Isis and Osiris, headed by Sarastro, enters to the sound of a solemn march. Sarastro tells the priests that Tamino is ready to undergo the ordeals that will lead to enlightenment. He invokes the gods Isis and Osiris, asking them to protect Tamino and Pamina (Aria: “O Isis und Osiris“).

Scene 2: The courtyard of the Temple of Ordeal

Tamino and Papageno are led in by two priests for the first trial. The two priests advise Tamino and Papageno of the dangers ahead of them, warn them of women’s wiles and swear them to silence (Duet: “Bewahret euch von Weibertücken“). The three ladies appear and tempt Tamino and Papageno to speak. (Quintet: “Wie, wie, wie“) Papageno cannot resist answering the ladies, but Tamino remains aloof, angrily instructing Papageno not to listen to the ladies’ threats and to keep quiet. Seeing that Tamino will not speak to them, the ladies withdraw in confusion.

Scene 3: A garden

Pamina is asleep. Monostatos approaches and gazes upon her with rapture. (Aria: “Alles fühlt der Liebe Freuden“) He is about to kiss the sleeping Pamina, when the Queen of the Night appears. She gives Pamina a dagger, ordering her to kill Sarastro with it and threatening to disown her if she does not. (Aria: “Der Hölle Rache kocht in meinem Herzen“). She leaves. Monostatos returns and tries to force Pamina’s love by threatening to reveal the Queen’s plot, but Sarastro enters and drives him off. Pamina begs Sarastro to forgive her mother and he reassures her that revenge and cruelty have no place in his domain (Aria: “In diesen heil’gen Hallen“).

Scene 4: A hall in the Temple of Ordeal

Tamino and Papageno are led in by priests, who remind them that they must remain silent. Papageno complains of thirst. An old woman enters and offers Papageno a cup of water. He drinks and teasingly asks whether she has a boyfriend. She replies that she does and that his name is Papageno. She disappears as Papageno asks for her name, and the three child-spirits bring in food, the magic flute, and the bells, sent from Sarastro. Tamino begins to play the flute, which summons Pamina. She tries to speak with him, but Tamino, bound by his vow of silence, cannot answer her, and Pamina begins to believe that he no longer loves her. (Aria: “Ach, ich fühl’s, es ist verschwunden“) She leaves in despair.

Scene 5: The pyramids

The priests celebrate Tamino’s successes so far, and pray that he will succeed and become worthy of their order (Chorus: “O Isis und Osiris“). Pamina is brought in and Sarastro instructs Pamina and Tamino to bid each other farewell before the greater trials ahead, alarming them by describing it as their “final farewell.” (Trio: Sarastro, Pamina, Tamino – “Soll ich dich, Teurer, nicht mehr sehn?” Note: In order to preserve the continuity of Pamina’s suicidal feelings, this trio is sometimes performed earlier in act 2, preceding or immediately following Sarastro’s aria “O Isis und Osiris“.[g][21]) They exit and Papageno enters. The priests grant his request for a glass of wine and he expresses his desire for a wife. (Aria: “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen“). The elderly woman reappears and warns him that unless he immediately promises to marry her, he will be imprisoned forever. When Papageno promises to love her faithfully (muttering that he will only do this until something better comes along), she is transformed into the young and pretty Papagena. Papageno rushes to embrace her, but the priests drive him back, telling him that he is not yet worthy of her.

Finale. Scene 6: A garden

Tamino and Pamina undergo their final trial; watercolor by Max Slevogt(1868–1932)

The three child-spirits hail the dawn. They observe Pamina, who is contemplating suicide because she believes Tamino has abandoned her. The child-spirits restrain her and reassure her of Tamino’s love. (Quartet: “Bald prangt, den Morgen zu verkünden“).

Scene change without interrupting the music, to Scene 7: Outside the Temple of Ordeal

Two men in armor lead in Tamino. They recite one of the formal creeds of Isis and Osiris, promising enlightenment to those who successfully overcome the fear of death (“Der, welcher wandert diese Strasse voll Beschwerden“). This recitation takes the musical form of a Baroque chorale prelude, to the tune of Martin Luther‘s hymn “Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein” (Oh God, look down from heaven).[h] Tamino declares that he is ready to be tested. Pamina calls to him from offstage. The men in armour assure him that the trial by silence is over and he is free to speak with her. Pamina enters and declares her intention to undergo the remaining trials with him. She hands him the magic flute to help them through the trials (“Tamino mein, o welch ein Glück!“). Protected by the music of the magic flute, they pass unscathed through chambers of fire and water. Offstage, the priests hail their triumph and invite the couple to enter the temple.

Scene change without interrupting the music, to Scene 8: A garden with a tree

Papageno despairs at having lost Papagena and decides to hang himself (Aria/Quartet: “Papagena! Papagena! Papagena!”) The three child-spirits appear and stop him. They advise him to play his magic bells to summon Papagena. She appears and, united, the happy couple stutter in astonishment and make bird-like courting sounds at each other. They plan their future and dream of the many children they will have together (Duet: “Pa … pa … pa …”).[i]

Scene change without interrupting the music, to Scene 9: A rocky landscape outside the temple; night

The traitorous Monostatos appears with the Queen of the Night and her three ladies. They plot to destroy the temple (“Nur stille, stille“) and the Queen confirms that she has promised her daughter Pamina to Monostatos. But before the conspirators can enter the temple, they are magically cast out into eternal night.

Scene change without interrupting the music, to Scene 10: The Temple of the Sun

Sarastro announces the sun’s triumph over the night. Everyone praises the courage of Tamino and Pamina, gives thanks to Isis and Osiris and hails the dawn of a new era of wisdom and brotherhood