Denmark has been relocated to somewhere in West Africa, while Old Fortinbras’s Norway is presumably nearby. Amid the brooding about Hamlet’s madness African drums pound out a rhythm. The set and cast are bedecked in bright colours and jazzy fabrics never previously seen in Elsinore. Indeed, most of the cast is of African descent – but don’t let that fool you into thinking this is a travesty of a production.

In Simon Godwin‘s epic vision, a vibrant, spectacular Hamlet challenges preconceptions but never forsakes the virtues found in most recent productions of clear interpretation, enunciation and basic human emotion. Indeed, this is the most passionate and moving version this reviewer has seen, and trust me I’ve seen many a Dane tread the boards. Only last week I was talking about Kenneth Branagh‘s glittering production, big on glamour but overlong and missing opportunities through flabby treatment of some key scenes.

By contrast, Godwin focuses the action to make every word count, and those that do not pull their weight are excised. The rationale for a twist on the default is made clearly – the colour and life contrast sharply with life outside the lure of Elsinore, all the more when the first scene in this production is a degree presentation ceremony at Wittenberg and Hamlet in suit and tie.

There he is away from home, an Elsinore that is at the same time warmly welcoming but also tainted by the horrors in recent memory: the death of his father and the hasty marriage between his mother and uncle, long before the ghost tells Hamlet the truth: “the funeral baked meats did coldly furnish forth the marriage tables.”

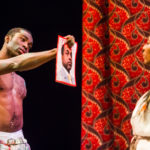

Responsibility for playing the Dane has been placed in the hands of Paapa Essiedu, a young actor born in England of Ghanaian roots. At 26 he has been fast-tracked into leading Shakespearian roles, and it’s not difficult to see why: Essiedu has a rare clarity and eloquence; he speaks to the heart, cries real tears and feels the part rather than acts it. This is a refreshed and refreshing translation into the depths of human emotion of a role traditionally performed as an exercise in poetic licence. I can think of no better example than the deep physical pain, revulsion and bile he summons up in his first soliloquy on learning of the marriage of his uncle to his mother:

“O, that this too too sullied flesh would melt,

Thaw and resolve itself into a dew,

Or that the Everlasting had not fixed

His canon ‘gainst self-slaughter! O God, God,

How weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable

Seem to me all the uses of this world!”

In fact, that almost all players are black, apart from being a refreshing change, helps cast the play in a new light; subtle nuances of context add depth of meaning to Shakespeare’s words. For example, this key speech was never more steeped in irony. If you consider how racism treats many human beings as subhuman, the whole purpose of the speech becomes more complex:

“What a piece of work is man! how noble in reason! how infinite in faculty! in form and moving how express and admirable! in action how like an angel! in apprehension how like a god! the beauty of the world, the paragon of animals!”

Clarence Smith‘s Claudius is deceptive. At face value he seems jovial, almost warm, more so than most in recent memory. But don’t underestimate the force of his revenge against the nephew whose knowledge threatens his life and his reign. He is in turns bully and wheedling meddler, though his rendition of “Oh, my offence is rank” soliloquy reveal an underbelly of nauseous self-loathing matching the performance of Patrick Stewart – even if this does not change his actions. This Claudius is resigned to eternal damnation, and seemingly revels in it.

By contrast, Tanya Moodie‘s Gertrude seems almost detached, as if the dilemma of being torn between grief for her late husband, her loyalty to her new husband, maternal duty to her son and shame for the hastiness of her remarriage has stifled her ability to act or participate emotionally. She echoes Claudius in chiding Hamlet, though you never believe her heart is in it. In the bedroom scene, she weeps piteously but cannot admit to herself the truth of her son’s words, fortified by the ghost’s visitation.

Of the Polonius family, the old man (Cyril Nri) is not quite the pompous buffoon and busybody you expect, though the worst excesses of his sonorous comic rambling have been judiciously trimmed. Like Claudius he appears good-natured, but unlike Claudius he lacks the power of deceit, his motive being the well-being of his children. Natalie Simpson makes for a spectacular Ophelia, one of the finest in recent years. I particularly liked her creation of her imaginary flowers by pulling out a lock of her hair, and of recreating the image of her late father on stage using a jacket and her own leggings. Her shocking grief and madness put Hamlet’s “antic disposition” into rich perspective.

You realise that when at the graveside Hamlet says “I loved Ophelia” he regrets being the cause of her misery and death with every fibre of his being, just as it fries the brains of her brother Laertes to see a happy-go-lucky beautiful sibling reduced to wailing madness. Marcus Griffiths plays the hot-headed son with surprising tenderness, but still gullibility to be taken in by Claudius’s murderous schemes while grieving for the unfortunate Polonius.

There is nary a bad performance to be seen, other perhaps than the Player King (Kevin N Golding) lacking the force and authority of the best – I’d have directed him to pretend his was Ralph Richardson! Nice to see a female Guildenstern in the form of Bethan Cullinane, one of a number of rising stars to match the prospective genius of Essiedu.

On the strength of this rendition, a touch of African sunshine fits the bill nicely. You wouldn’t want it in every Shakespearian adaptation, but it is a most refreshing change. If that sounds dismissive, it is certainly not intended as so. For all the trappings, this is a compelling reading and performance, one every dedicated Shakespearian follower should see if at all possible.

***** (5 stars)