Beatrice McCready: You took Amanda with you?

Helene McCready: Well, what am I gonna’ do? Leave her in the car, Bea? I don’t got no daycare. It’s really hard bein’ a mother. It’s hard raisin a family, you know? All on my own. But God made you barren, so you wouldn’t fuckin’ know. So I understand, Bea, okay?

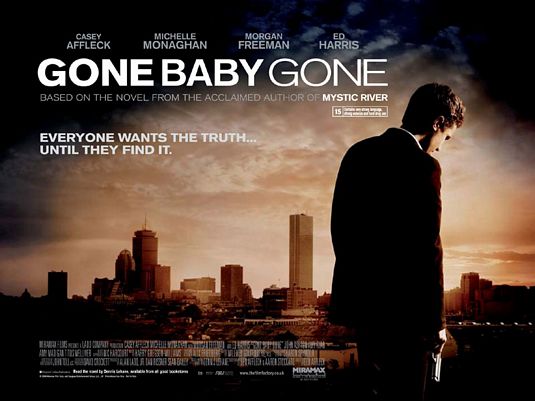

Ignore for a moment the plot twists in Ben Affleck‘s 2007 directorial debut, a powerful thriller called Gone Baby Gone, and focus instead on the underlying dilemma: what is best for children – to stay with parent or parents who are troubled, inattentive, neglectful, but essentially loving, or to be taken and transplanted by deception into another home with more money and a better life?

The film offers no solutions, though in this case the crack-smoking mother turns her life around, at least to some degree. Perhaps some descend into serious addiction and death, with long-suffering children being farmed out to adoptive grandparents, mentally scarred from the experience.

It’s a big enough decision to offer kids for adoption or fostering voluntarily, and also a formidably difficult task for the new family to negotiate a way forward towards happiness. In short, no easy answers and each case must be judged on its merits.

The point about this plot is that the adoption is achieved through a complicated and bungled kidnapping of the 4-year old, which begins as a way of warning relatives off mingling with the proceeds of crime and ends. It goes via a set-up rendezvous where the stooge is a Haitian gangster called “Cheese” (Edi Gathegi doing a fine job of sounding menacing) and an assumption that the child died in the process; and it ends with the truth, the simplest solution you could expect and therefore proving correct Occam’s Razor.

You could see it coming because the most celebrated star in this movie, Morgan Freeman, vanishes half way through, and there was no way he was going to disappear without some influence on the denouement. Actually, the clue is laid early on when as police Captain Jack Doyle he makes a point of saying that he lost a child, from which we can draw the conclusion that he is not above saving another child to complete his family, late in life.

Except… that isn’t the end. The ending sees the child living apparently happy with mum, who goes out and leaves the principle protagonist, Casey Affleck‘s Patrick Kenzie, minding the little girl. “Is that Mirabelle?” he asks about her doll. “Annabelle” replies young Amanda (Madeline O’Brien), and goes on playing.

A delicately poised ending, all the more poignant since at the mother, Helene, (Amy Ryan) made an earlier TV broadcast in which she was asked if she had advice for other parents. She responds, “hold on tight to them.” On another occasion she says this to Kenzie:

“[crying] I know I fucked up. I just want my daughter back. I swear to God, I won’t use no drugs no more. I won’t even go out; I’ll be fucking straight. Cross my heart.”

So mother’s take their children for granted but weep and mourn when they’re gone, but the fact is you can’t ever wrap them in cotton wool either. Every day offers risks, and even the most attentive mother has to leave their child sometimes. In fact, the more suffocated by the relationship the more likely the child will rebel and do their own thing. There comes a point where you simply have to let go – but for a 4-year old the reckoning is that much harder.

Getting back to the plot, while Cap’n Jack and his dodgy detectives (Sergeant Remy Bressant played with seething sleaziness by the excellent Ed Harris, and podgy Detective Nick Poole in the person of John Ashton looking ready for retirement and a bar space to fill) attempt to, or rather avoid solving (Bressant is thick as thieves with Titus Welliver‘s aggressively moustachioed Lionel, uncle of the little girl), Amy Madigan‘s Aunt Bea wades in and recruits Kenzie and girlfriend Angie Gennaro (Michelle Monaghan, also in Source Code and True Detective), PIs in missing people cases, to supplement the lacklustre police efforts. No accident that the cops aim to obfuscate, but not difficult to see why in hindsight; delicious irony then as Kenzie tells Bressant that he believes everything the police tell him.

This yields initially good results, since despite his babyish looks Kenzie is a tough guy prepared to stand his ground and get answers. It is he who traces the link to Cheese, sets up a meeting and participates in the would-be exchange that goes horribly wrong. But you can see his brooding dissatisfaction at how things turn out – Kenzie will not be satisfied until he finds the truth, and so he does.

I’ll leave you to find the rest of the twists by yourself, but suffice it to say Affleck, with help from his brother and a fine cast, does an excellent job of building the atmosphere in this tense thriller. But if he’s done his job properly, your closing thoughts must be for all the many children who don’t come back, who die or are abused, who live in unhappy homes as a result of parental crises or self-inflicted harm, who are fought over, hurt and traumatised by life at an early age and suffer through the trauma for the rest of their days, passing it on to their own children. Childhood was never meant to be like that, even if the child in this case appears to be the happiest person on view.