Side Effects is and isn’t a movie about the impact of depression and the medication designed to treat the illness. Regular readers will know depression is a topic of some considerable concern to me (see my blog Black Dog), and to give it credit many of those issues are addressed in the first half of the movie – describing the hopelessness and quoting some well-known chestnuts like “sailing into a poisonous fog” and the definition that depressives “are unable to construct a future” as if the scriptwriter had read a couple of books and wanted to get the quotes in to show he’d done some research.

All of these will sound very familiar to sufferers, as will the debate about therapy and the various medications prescribed for the condition – and indeed the pressure practitioners come under to participate in studies and reward doctors for prescribing their drug. The greatest strength of the movie is to identify some very real concerns of sufferers of mental illnesses, apply a degree of insight into the curge of the depressive state of mind and open debate on the topic.

But the problem in the final analysis with Side Effects is that this is just a smoke screen for what is essentially a slick and stylish Hollywood thriller in which one of the leading protagonists may or may not suffering from depression, kills her husband in what may be deliberate murder or executed while sleepwalking (depending on your point of view) and is playing or being played with by two rival psychiatrists, one of whom will be destroyed regardless of the findings of the court.

The denouement takes one view, and in so doing casts a cynical shadow over the real nature of depression, one that distorts the mirror of reality experienced by thousands of victims. That it takes such a view could be very damaging if it means the credibility of medical practitioners and the ability of patients to be taken seriously is impacted, were it to be viewed seriously.

I suspect the august bodies responsible for practitioners of healing for the mentally ill took the view that this is all hokum and therefore chose to ignore it. So if you do go and see this, allegedly Sodbergh’s final movie, my recommendation is to take it with a bucket of salt and don’t expect that Hollywood is taking seriously the true nature of depression. This is a construct on which to hang a movie, and nothing more – though many sufferers of this wretched illness will feel put out and cheated that their suffering has been denied by a trick movie.

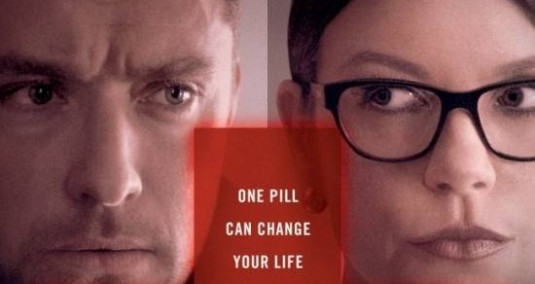

If you do take it at face value, you will recognise that the three principles do a fine job, and arguably the character of Dr John Banks is as fine a performance as ever delivered on screen by Jude Law. While Law’s credibility in the role is high, the relative speed in elapsed screen time in which he grasps the truth, while all around him are sceptical, seems to work at indecent hast, to put it mildly.

It costs him his wife and child, his practice and his role on a drug study, yet he pursues the case like a dog with a bone. I expect many psychiatrists in such circumstances might have given up the ghost, but not Dr Banks. He hangs on in there, racked as he is with self-doubts but an inner resilience that sees him give himself therapy to be a survivor where some of his patients materially fail.

Rooney Mara’s vulnerable and fragile beauty, Emily Taylor, comes out pretty well as a performance, though how credible she is as a depressive I will leave you to judge – though how realistic her character is may strike you as dubious.

If she is putting it on, would she drive her car into a brick wall without braking, even if she did have a seatbelt on? Would she know and be able to exploit side effects in the medication? Would she adopt such a high risk strategy that could so easily have failed and have resulted in her being in chokey for the rest of her days and/or her psychiatrist too? Many questions you might want to consider there, quite apart from the actual impacts of medicines on trial. My view is that the plot stretches credibility on many occasions.

Portraying hopelessness is traditionally a trait more at home with the hams of Hollywood, though Mara does her best to make the role at least part-way credible. However, given the multiple levels of deception practised, keeping it up was always going to be a tall order. In the final analysis (to coin a phrase), Mara’s mask slips a way before the ending.

Not difficult to see why Channing Tatum‘s ex-con all-American rich kid Martin would fall for Taylor, though his character is so thinly sketched you have barely got to know him before he is sliced up with a kitchen knife and writhing along the kitchen floor. To me, he appears more as an American footballer than a financial whizz, which is probably indicative of miscasting more than any specific failure on Tatum’s part.

The weakest of the three leads is undoubtedly Catherine Zeta Jones, equipped though she is with glasses to provide that instant intelligence quotient. I did not believe she was a psychiatrist, still less several other revelations about her intimate past. Could be that this was a casting blip, since it is a part which demands an actress with hidden depths and more subtlety than the ex-Mrs Douglas can typically deliver, so the part seems to me at least slightly out of her depth, though in that respect she is not alone.

Having said that, it’s interesting that two out of three stars in this movie are British, one playing an American. To paraphrase Colin Welland, the Brits are back and doing quite nicely, thank you very much!

Oh, and one more thing you may care to take account of when deciding whether to see this movie: I guessed which way the wind was blowing, plot-wise (as Americans would say) within 15 minutes. It left a chill down my spine, though not for the reasons the director might have hoped. You may take less than 15 minutes, you may take more, but it will probably not be a total shock to you. I know the trailers call it an “edge of the seat thriller”, and it is indeed highly competent in many areas, though in my humble opinion the denouement lets it down by virtue of telegraphing the plot twist: it is the only place the movie could end up.

For all the effect that it is a fair movie taken as such as a psychological thriller, it is something of a shame that the opportunity to give a lasting impression about the true nature of depression was not taken – and indeed an irresponsible view given the suffering of many with this appalling illness. After all, you would not accuse patients with a brain tumour or a stomach ulcer of faking it, now would you?