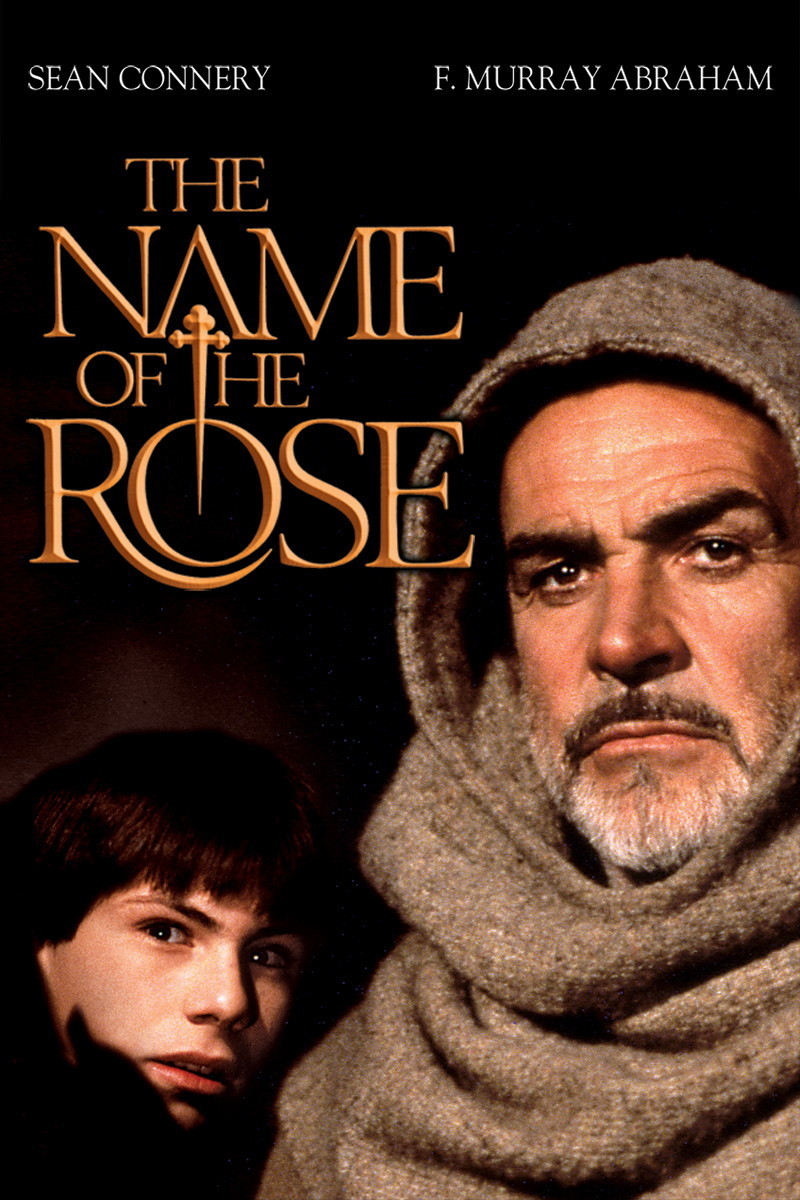

I read Umberto Eco‘s novel The Name Of The Rose once. As you would expect for such an erudite author, it is a rich concoction of academic debate, history, philosophy, theology, whodunnit and occasional glimpses of sly humour. Some of it is hard going, but it’s also compelling reading, even if at the time I struggled to pick up all the references, nods and winks, of which there are many.

Translating such a work to the big screen was always going to be tricky, but cometh the hour, cometh Jean-Jacques Annaud. From Wikipedia:

Director Jean-Jacques Annaud once told Umberto Eco that he was convinced the book was written for only one person to direct, that is to say himself. He felt personally intrigued by the project, among other things because of a lifelong fascination with medieval churches and a great familiarity with Latin and Greek. Annaud spent four years preparing the film, traveling throughout the United States and Europe, searching for the perfect multiethnic cast with interesting and distinctive faces.

The Name Of The Rose lacks some of the intellectual rigour of the book, but boy, does it make for one riveting movie. To quote Paul Howlett in the Guardian:

This medieval detective story is adapted from Umberto Eco’s novel about serial murder in a remote Italian monastery. Annaud is in his element in the middle ages, directing with a real feel for a time that could be both brutish and transcendent. Sean Connery is superb as William of Baskerville, who sets out to decipher the secret and outwit F Murray Abraham‘s saturnine grand inquisitor.

Connery may at first sight appear an unlikely choice for a well-read Franciscan monk, but he takes to it like a duck to water, engaging with Michael Lonsdale‘s Benedictine Abbot with the help of calm logic and refusing to be carried away by those on both sides who take the murders (depicted in grisly detail) to be a sign of supernatural intervention and the sign of the devil. In that respect, William of Baskerville (a name cunningly chosen by Sr Eco) is very like a learned Sherlock Holmes and William of Occam (a Franciscan), relying as he does on intuition and observation, as well as a well-honed intellect to see off those who would jump to conclusions, of whom there are many at the Abbey.

He is assisted in his observations by his curious young novice, Adso of Melk, played with knowing naivety by a young Christian Slater, the two attending the monastery for a great debate on the state of religion and their vows of poverty, but find the inhabitants of the establishment, primarily a production centre for illuminated books which are stored in the hidden depths of the labyrinth of the Great Tower, are distracted by the grotesque deaths of several monks engaged in illustrating these works of art and literature. Adso is also distracted by a peasant girl, though not without the knowledge of his master. Wikipedia, once more:

He resisted suggestions to cast Sean Connery for the part of William because he felt that the character, who was already an amalgam of Sherlock Holmes and William of Occam, would become too overwhelming with “007” added. Later, after Annaud failed to find another actor he liked for the part, he was won over by Connery’s reading, but Eco was dismayed by the casting choice and Columbia Pictures pulled out, as Connery’s career was then in a slump. Christian Slater was cast through a large-scale audition of teenage boys. For the wordless scene in which the Girl seduces Adso, Annaud allowed Valentina Vargas to lead the scene without his direction. Annaud did not explain to Slater what she would be doing in order to elicit a more authentic performance from the actors.

The arch enemy of reason in this debate is Abraham’s evil and zealous inquisitor Bernado Gui, called to the Abbey when the Abbot is unnerved by William’s failure to recognise evil, and evil he sees in all things – chickens and black cats, for example. William bides his time, since to question an inquisitor demands recantation or death for heresy. In real life, Gui was a Dominican monk and inquisitor, known best for his writings, notably “Conduct of the Inquisition into Heretical Wickedness.” The movie ultimately departs from fact by killing off Gui in the last reel, where in real life he died peacefully in France. Here he makes a perfect pantomime villain, to be booed and hissed.

A demonic scapegoat is required and there is the disfigured Brother Salvatore in the person of Ron Perlman, a staggering performance at every level playing “a demented hunchback who speaks gibberish in various languages” and with a past that included a dalliance with heretics. In fact, Perlman is also lumbered with prosthetics but does a superlative job in conveying a pleading simpleton, cast out by all society, one worthy of a best supporting actor gong. The Benedictine monks are played superbly to a man by an international cast, including the blind and grumpy Venerable Jorgi de Burgos (Feodor Chaliapin Jr.)

The recurring underpinning to these events is a debate about laughter – whether, as Venerable Yorgi believes, laughter is the work of the devil. This is ultimately the key to the story, one that is artfully told. The labyrinth is both real and metaphorical, and beautifully created for the screen in a way that pre-empts the staircases at Hogwarts by some years.

Visually, the movie is a thing of great beauty, with rich colours and exquisite shots, but the bleak backdrop overlooked by the magnificence of the Abbey is, strangely enough, a fabrication. Wikipedia again:

The exterior and some of the interiors of the monastery seen in the film were constructed as a replica on a hilltop outside Rome, and ended up being the biggest exterior set built in Europe since Cleopatra. Many of the interiors were shot at Eberbach Abbey, Germany. Most props, including period illuminated manuscripts, were produced specifically for the film.

The result is an extraordinary movie, one which can engage people who previously thought a tale of 14th Century monks was not their thing – but then is this simply a detective story with a period feel? Eco would argue not, since the debate is very much of its time. But then the ultimate purpose is spoken right at the death, as it were…

The book’s last line, “Stat rosa pristina nomine, nomina nuda tenemus” translates literally as “Yesterday’s rose endures in its name, we hold empty names”. The general sense, as Eco pointed out, was that from the beauty of the past, now disappeared, we hold only names.

Good Job! Keep up the good work