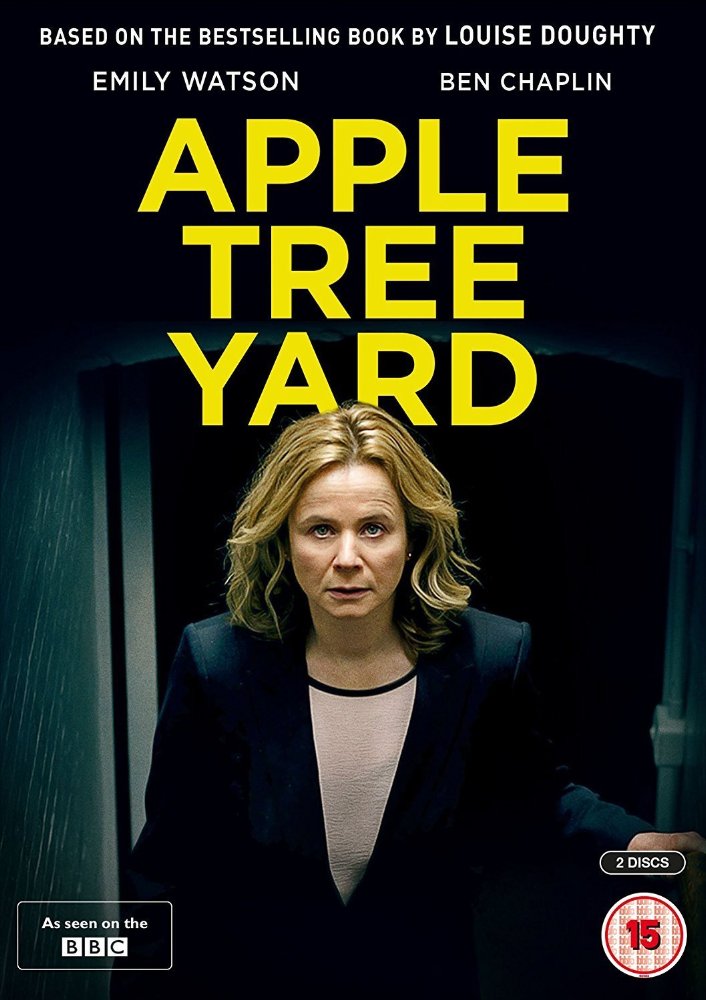

What separates Apple Tree Yard from many other TV mini-series thrillers adapted from well-reviewed books is not necessarily the quality of the source material, gripping though it unquestionably is.

What stands out is the combination of deep moral dilemmas and close, intimate shots that linger for an uncomfortably long time, giving the characters nowhere to hide their burning emotions, none more so than Emily Watson‘s otherwise respectable Dr Yvonne Carmichael (indeed, some time is taken for scene-setting to demonstrate Dr Carmichael’s respectability as an upright and august member of society, as is normal in such dramas.)

But…. boy! Does the good doctor, an eminent scientist in her own right with a decent husband, teenage son and pregnant daughter, suffer when she takes the irrational and impulsive decision to take on a wild and secretive affair with a man she knows only as Mr X. The thrill of the moment may appeal, but you repent at leisure when it turns out the man has hidden personality flaws and a history.

However, the most harrowing moment Dr Carmichael faces is a rape scene and its physical and emotional aftermath. This appalling, nightmarish scene is handled as effectively as the rape scene in The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, and the form of revenge is just as important to both stories. It isn’t directly violent, though Dr Carmichael does later list her injuries matter-of-factly to indicate this is much more than emotional carnage.

What comes out more successfully than any other screen rape is how the perpetrator continues as if nothing has changed and as if the rape were actually consensual. Indeed, the perpetrator here, a fellow academic Dr Carmichael has known a long time and never thought of as being in any way violent or dangerous, sends provocative messages to demonstrate he is stalking her, knowing full well the impact they will have on his victim.

The nerve-shredding effect on the normally composed Dr Carmichael is understandable but seldom truly appreciated when such stories appear in the press or on TV, nor yet in court where protocols are followed and the victim is interrogated in cross-examination as if she were the guilty party. This is unquestionably the reality of rape and the reason why so many victims failed to report the crime for so many years. If the tide is turning, you still wonder how many rapes still go unreported.

But this ordeal is only part of the drama, for there are twists here. Not only must Dr Carmichael learn to live with the post-traumatic stress and defend herself against the charge of murder actually perpetrated by her secret lover, but of which she knew nothing. Proving she knew nothing and is merely an innocent victim bound up in circumstances beyond her imagining is a very uphill struggle, and bear in mind the perceptive line here about who wins in court being the person who tells the best story. How true!

No, there is more: she has to construct a rationale for what really happened, and therein lies the twist, one I shall not divulge. As for the moral of the tale, you could argue that it does not tell the viewer didactically not to engage in games of sexual politics, merely to be very sure and very careful if he/she does so, Caveat Emptor, as it were.

In fact, this is a shallow reading of what is, psychologically, a very cleverly layered tale with shades of desire every viewer can relate to at some level, no matter how virtuously we paint ourselves. A better moral might be that good communication prevents many a disaster, since Dr C chooses not to communicate effectively with her husband or family, at no little cost; nor with her lover, almost at greater cost. She is at the stage of life where she wants to rediscover herself, her individuality, her humanity, which discovery comes at a price.

You need a good cast to get away with this level of exposure to raw emotion and feeling. Watson, perhaps slightly out of her usual domain, does a remarkable job in defining her character’s roles: the authoritative academic, the wife and mother, the sexy and impulsive lover, the grieving victim and the defendant whose deepest secrets are exposed in that heart-stopping but inevitable moment of exposure. Perhaps she knew it was always going to come out somehow, yet she is unprepared for the moment, still less for her family watching as her betrayal is laid out for all to hear.

As her fellow-academic husband Gary, Mark Bonnar also comes out with flying colours and flying emotions: contrition for his own past misdemeanours, sympathy for his wife tempered by frustration for the apparent contempt she shows towards him, good fatherhood but a desire for things to be better.

Ben Chaplin‘s Mr X (aka the aptly named Mark Costley) is a marked contrast to Yvonne’s husband, being a man who sees through her desires and knowingly feeds them. She does not want commitment, she wants fun. That he has a past is certain, yet all she knows is that he has a wife, no more, yet her life is an open book. Chaplin does a difficult job here, since suppressing the history is contrary to how actors go about their job; he wears it lightly, where his lover’s weariness is etched upon her face. The exposé of his past is left to the courts, yet he remains inscrutable to the last.

In that sense, Mr X could be a sociopath or at least a narcissist, yet the precise diagnosis is the subject of some discussion in court – borderline personality disorder seems the closest. Of empathy he has sufficient to understand the rape and to act upon his lover’s wishes to end the stalking and suffering. The only time I can recall a similar experience is playing “actoids” in Alan Ayckbourn‘s Comic Potential, since they had no feeling whatever – and that was remarkably tricky to do well.

Ah, I nearly forgot! In case you were wondering, Apple Tree Yard of the title is an alleyway parallel to Jermyn Street in the environs of St James’ Square in London. It’s where some of the illicit coupling goes on, later referred to in court. The risk of what would happen if you were caught? See here – but the presence of a possibly non-working CCTV camera is just one of several dilemmas captured here.

Apple Tree Yard is unquestionably well-devised high-quality drama, understated yet delving into areas of the psyche rarely visited by TV thrillers but remaining compelling to the last. It provokes thought that lasts well beyond the end of the four chapters, which is as good a definition of excellent TV drama as any I can think of. Certainly not, in the words of Frank Lloyd Wright, “chewing gum for the eyes.”