“Magical realism is defined as what happens when a highly detailed, realistic setting is invaded by something too strange to believe… There is a reason magical realism was born in Colombia.”

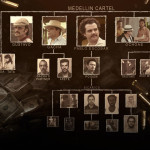

Narcos series 1 is a 10-part docudrama focused on the rise and fall of Pablo Escobar – Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria, to give him his full name (Wagner Moura) and the Medellín drug cartel, unquestionably the most profitable and lethally opportunistic exploitation of cocaine anywhere at any time – to the extent that the cartel at its peak controlled 80% of global production and distribution.

After a fairly benign and amateurish start, the cartel toughened up and became among the most ruthless and bloodthirsty gangs found anywhere. They corrupted the country, such that almost everyone in positions of authority was being paid off, and those who challenged the cartel, or even got too close, ended up in the morgue.

This is undeniably a tale worth telling, and a fascinating one at that, though there are many excellent documentaries about Escobar and the Medellín Cartel giving first-hand accounts (see here, here, here, here and here for example.) Make no mistake, this is a subject already much discussed.

Narcos says much about Colombian culture that one man could become richer than the whole country, but also much about American society that it woke up late to what was going on and came down in ways that were hidden from public view but often draconian – which in turn says much about American foreign policy before and since.

While most of those portrayed are Colombian, and indeed speak Spanish rather than English-with-a-funny-accent-pretending-to-be-foreign, it will not surprise anyone that the narrator is an American (ie. gringo) DEA agent by the name of Steve Murphy (Boyd Holbrook), even if the principle protagonist is the most successful drug overlord in history. Murphy’s languid Texan drawl tells the story, including the links between scenes. This is of course a dramatic device, since the voiceovers tell a story in hindsight that none of the characters could have known at the time, much less imagined the interactions right up to and including presidential level.

But at least, unlike Suffragette, the story is at least told through a real person; indeed almost all characters seem to be based on real people, even if most of the dialogue and some of the scenarios are fictionalised. In fact, by the standards of most docudramas, the historical accuracy of Narcos is probably up there with the best, even allowing for the health warning about truth and fiction displayed at the beginning of each episode. That is to say that there are changes in characters and locations, and interpretations of disputed events with which many would disagree.

The gringo American perspective would certainly put a number of Colombian noses out of joint since there was, even at that time, much more to Colombia and its people than the drug war portrayed. Is this American propaganda? This blog certainly takes the view that a very one-sided portrait is being painted. As is pointed out in the series, the Colombians are a proud people and do not take kindly to condescension from Americans, even if on occasions it cost them many lives.

Those who paid the ultimate price for speaking out included Rodrigo Lara Bonillo, the minister who stood up to Escobar’s organisation, and Presidential candidate Luis Carlos Galán Sarmiento; the demise of both men is featured in Narcos. It was Galán’s successor César Gaviria (no relation to Escobar, a man who survived to tell the tale and to bring Colombia back from the brink of being a drug state) and Colonel Horacio Carillo (fictional but based on the original commander, Colonel Hugo Martinez, who does feature in series 2 after “Carillo” dies at the hands of Escobar) who set up the incorruptible Search Blocs that eventually tracked down and killed Escobar (wait for series 2) – a Colombian version of Eliot Ness‘s “Untouchables.”

Much of the first series is a game of cat and mouse as Murphy and his partner Javier Peña (Pedro Pascal) try to find ways of outwitting el Patron. But even on the side of the law there are moral dilemmas, such as hiding the fugitive M-19 guerrilla who had direct evidence linking Escobar to the Palace of Justice siege, during which many judges were killed and hundreds of thousands of pages of evidence linking Escobar to criminal acts and drug exports were destroyed. By turn, Escobar is seen offering bigger and bigger bribes and waging a war he ultimately could not win – though he certainly came close.

Disregarding the nature of the subject matter for a moment, it still had to be fictionalised and brought to life in a way that appealed to viewers. Phrasing it as a real life exercise in magic realism was a clever ploy, starting with the quote at the top of this page. It sets the tone that is pursued through to the end.

Indeed, if there is an underlying theme it is moral relativism – the multiple shades of ambiguity, where even the bravest opponents of the cartel admit to having taken drug money; the poor take handouts from the man who says he is “a poor man with money” and apparently love the man who caused misery to millions in another country.

The choice of a charismatic Brazilian actor to play Escobar works brilliantly. Moura is less chubby about the face than Escobar, but his capture of the manner and personality of the man wielding the power, money and drugs is contrasted sharply with his own view that he is but a humble peasant at heart. A sensational performance, dripping with charisma and the very real fear of death, such was the man.

In this shady world, nobody is innocent or untainted – Escobar paid off public officials by the million, many of whom were working simultaneously for both sides, and had killed those who dared defy him. Were the police and special forces with their unauthorised missions any better?

Worse still, Gaviria’s government did a deal with the devil when he kidnapped prominent figures in the media, especially the daughter of the former president – who was accidentally killed in a raid by security services. Ultimately, the Search Blocs were prevented from attacking their target as Gaviria caved in and negotiated a deal – the terrorists held all the trumps in this case. The president allowed Escobar to build his own prison and admit one minor charge, which brings to mind the Thatcher quote: “We must never, ever give in to terrorists.” Would she have thought differently if her children had been kidnapped by bandits with more power and money than the state?

The weakest part of Narcos, apart from the very one-sided portrayal of Colombia? The fact that it ends after the siege of la Catedral, Escobar’s bespoke prison – not far from Escobar’s death but only left on a cliff-hanger for one reason: to justify a second series of Narcos. Yes, leaving them wanting more is one thing, but in this case it would have been far better to complete the task in one series. That apart, a very decent attempt at capturing magical realism through events that would once have seemed impossible – though in the light of recent events in Paris little or nothing would surprise any more.