Bob Dylan is far from being alone in reinventing himself at regular intervals for new audiences, but in a career spanning over 50 years he has succeeded in inspiring succeeding generations by virtue of an enigmatic personality, but more especially a talent for writing songs that linger long in the memory and speak to people much in the way that Morrissey did to a generation of Smiths fans living in Manchester bedsits. Dylan was always the master of this particular skill, courting controversy at every turn but with the ability to provoke emotion at every turn, so if he looks to you now like a grizzled old has-been – don’t write him off!

In his younger days it was a folk heritage from the Woody Guthrie tradition that inspired Dylan to write and perform, acoustic guitar with harmonica stand for support. Robert Allen Zimmerman morphed into the persona of his alter ego Bob Dylan (after the poet Dylan Thomas) in the late 50s and by 1961 he was living in New York and playing the clubs of Greenwich Village. The legal change to Dylan came in 1962, and he has scarcely been out of the headlines ever since.

His full story is detailed in Wikipedia and in many other places, but you sense that no biographer ever quite caught the essence of the man – there is an elusive quality about Dylan that he strives to maintain. I’m quite sure that enjoys being the man of mystery, which is barely elucidated by his own volume of autobiography. In many ways it is as enigmatic as many of his lyrics. Hardly surprising then that views of the man and his impact on the musical scene are totally polarised. Courtesy of Wikipedia:

Bob Dylan has been described as one of the most influential figures of the 20th century, musically and culturally. He was included in the Time 100: The Most Important People of the Century where he was called “master poet, caustic social critic and intrepid, guiding spirit of the counterculture generation”. President Barack Obama said of Dylan in 2012, “There is not a bigger giant in the history of American music.” Biographer Howard Sounes placed him among the most exalted company when he said, “There are giant figures in art who are sublimely good—Mozart, Picasso, Frank Lloyd Wright, Shakespeare, Dickens. Dylan ranks alongside these artists.”Rolling Stone magazine ranked Dylan at Number Two in their 2011 list of “100 Greatest Artists” of all time. In their 2008 assessment of the “100 Greatest Singers”, Rolling Stone ranked him at #7.

Initially modeling his writing style on the songs of Woody Guthrie, the blues of Robert Johnson, and what he termed the “architectural forms” of Hank Williams songs, Dylan added increasingly sophisticated lyrical techniques to the folk music of the early 1960s, infusing it “with the intellectualism of classic literature and poetry”. Paul Simon suggested that Dylan’s early compositions virtually took over the folk genre: “[Dylan’s] early songs were very rich … with strong melodies. ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ has a really strong melody. He so enlarged himself through the folk background that he incorporated it for a while. He defined the genre for a while.”

When Dylan made his move from acoustic music to a rock backing, the mix became more complex. For many critics, his greatest achievement was the cultural synthesis exemplified by his mid-1960s trilogy of albums—Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisitedand Blonde on Blonde. In Mike Marqusee‘s words: “Between late 1964 and the summer of 1966, Dylan created a body of work that remains unique. Drawing on folk, blues, country, R&B, rock’n’roll, gospel, British beat, symbolist, modernist and Beat poetry, surrealismand Dada, advertising jargon and social commentary, Fellini and Mad magazine, he forged a coherent and original artistic voice and vision. The beauty of these albums retains the power to shock and console.”

One legacy of Dylan’s verbal sophistication was the increasing attention paid by literary critics to his lyrics. Literary critic Christopher Ricks published a 500-page analysis of Dylan’s work, placing him in the context of Eliot, Keats and Tennyson,[355] and claiming that Dylan was a poet worthy of the same close analysis. Former British poet laureate Sir Andrew Motion argued that his lyrics should be studied in schools.[357] Since 1996, academics have lobbied the Swedish Academy to award Dylan the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Dylan’s voice was, in some ways, as startling as his lyrics. New York Times critic Robert Shelton described his early vocal style as “a rusty voice suggesting Guthrie’s old performances, etched in gravel like Dave Van Ronk’s.” David Bowie, in his tribute, “Song for Bob Dylan“, described Dylan’s singing as “a voice like sand and glue”. His voice continued to develop as he began to work with rock’n’roll backing bands; critic Michael Gray described the sound of Dylan’s vocal on his hit single, “Like a Rolling Stone”, as “at once young and jeeringly cynical”. As Dylan’s voice aged during the 1980s, for some critics, it became more expressive. Christophe Lebold writes in the journal Oral Tradition, “Dylan’s more recent broken voice enables him to present a world view at the sonic surface of the songs—this voice carries us across the landscape of a broken, fallen world. The anatomy of a broken world in “Everything is Broken” (on the album Oh Mercy) is but an example of how the thematic concern with all things broken is grounded in a concrete sonic reality.”[364]

Dylan’s influence has been felt in several musical genres. As Edna Gundersen stated in USA Today: “Dylan’s musical DNA has informed nearly every simple twist of pop since 1962.” Many musicians have testified to Dylan’s influence, such as Joe Strummer, who praised him as having “laid down the template for lyric, tune, seriousness, spirituality, depth of rock music.” Other major musicians to have acknowledged Dylan’s importance include John Lennon,Paul McCartney,Pete Townshend, Neil Young, Bruce Springsteen, David Bowie, Bryan Ferry, Nick Cave, Patti Smith, Syd Barrett, Joni Mitchell, and Tom Waits. More directly, both the Byrds and the Band, two 1960s contemporary groups with some measure of influence on popular music themselves, largely owed their initial success to Dylan: the Byrds with their hit of “Mr. Tambourine Man” and subsequent album; and the Band for their association with him on tour in 1966, on retreat in Woodstock, and on their debut album featuring three previously unreleased Dylan songs.

Some critics have dissented from the view of Dylan as a visionary figure in popular music. In his book Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom, Nik Cohn objected: “I can’t take the vision of Dylan as seer, as teenage messiah, as everything else he’s been worshipped as. The way I see him, he’s a minor talent with a major gift for self-hype.” Australian critic Jack Marx credited Dylan with changing the persona of the rock star: “What cannot be disputed is that Dylan invented the arrogant, faux-cerebral posturing that has been the dominant style in rock since, with everyone from Mick Jagger to Eminem educating themselves from the Dylan handbook.” Discussing the perplexing nature of Dylan’s image and allure, Duke University professor Shalom Goldman said, “Another thing that makes him so intriguing is that he creates expectations and then seems to lead to disappointments. You end up irritated, yet drawn to him.”

Joni Mitchell described Dylan as a “plagiarist” and his voice as “fake” in a 2010 interview in the Los Angeles Times, in response to a suggestion that she and Dylan were similar since they had both changed their birthnames. Mitchell’s comment led to discussions of Dylan’s use of other people’s material, both supporting and criticizing him. In a 2012 interview with Mikal Gilmore in Rolling Stone, Dylan responded to the allegation of plagiarism, including his use of Henry Timrod’s verse in his album Modern Times, by saying that it was “part of the tradition”.

If Dylan’s legacy in the 1960s was seen as bringing intellectual ambition to popular music, now that he has passed the age of 70, he has been described as a figure who has greatly expanded the folk culture from which he initially emerged. As J. Hoberman wrote in The Village Voice, “Elvis might never have been born, but someone else would surely have brought the world rock ‘n’ roll. No such logic accounts for Bob Dylan. No iron law of history demanded that a would-be Elvis from Hibbing, Minnesota, would swerve through the Greenwich Village folk revival to become the world’s first and greatest rock ‘n’ roll beatnik bard and then—having achieved fame and adoration beyond reckoning—vanish into a folk tradition of his own making.”

Whether you loved or hated the man, his influence is undeniable – and the number of artists covering his songs to great effect and sometimes huge hits is testimony to that influence. This blog barely scratches the surface of the great songs and great lyrics written by Dylan, and the many barriers, sales and genres he crossed in writing them. For

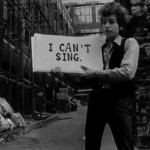

As Dylan himself said, he was never a great singer, with a voice characterised by a nasal whine and drawled delivery, though contrary to the views of many he could always sing in key. As a musician, firstly on acoustic and later on electric guitars, he could play but not up there with the best. The fact that he did convert to electric was almost more important symbolically than what he played. Wikipedia again:

Dylan’s April 1965 album Bringing It All Back Home was yet another stylistic leap, featuring his first recordings made with electric instruments. The first single, “Subterranean Homesick Blues“, owed much to Chuck Berry‘s “Too Much Monkey Business“; its free association lyrics have been described as both harkening back to the manic energy of Beat poetry and as a forerunner of rap and hip-hop. The song was provided with an early music video which opened D. A. Pennebaker‘s cinéma vérité presentation of Dylan’s 1965 tour of Great Britain, Dont Look Back. Instead of miming to the recording, Dylan illustrated the lyrics by throwing cue cards containing key words from the song on the ground. Pennebaker has said the sequence was Dylan’s idea, and it has been widely imitated in both music videos and advertisements.

The second side of Bringing It All Back Home consisted of four long songs on which Dylan accompanied himself on acoustic guitar and harmonica. “Mr. Tambourine Man” quickly became one of Dylan’s best known songs when The Byrds recorded an electric version that reached number one in both the U.S. and the UK charts. “It’s All Over Now Baby Blue” and “It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” were acclaimed as two of Dylan’s most important compositions.

In 1965, as the headliner at the Newport Folk Festival, Dylan performed his first electric set since his high school days with a pickup group drawn mostly from the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, featuring Mike Bloomfield (guitar), Sam Lay (drums) and Jerome Arnold (bass), plus Al Kooper (organ) and Barry Goldberg (piano). Dylan had appeared at Newport in 1963 and 1964, but in 1965 Dylan, met with a mix of cheering and booing, left the stage after only three songs. One version of the legend has it that the boos were from the outraged folk fans whom Dylan had alienated by appearing, unexpectedly, with an electric guitar. Murray Lerner, who filmed the performance, said: “I absolutely think that they were booing Dylan going electric.” An alternative account claims audience members were merely upset by poor sound quality and a surprisingly short set. This account is supported by Kooper and one of the directors of the festival, who reports his audio recording of the concert proves that the only boos were in reaction to the MC’s announcement that there was only enough time for a short set.

Nevertheless, Dylan’s 1965 Newport performance provoked a hostile response from the folk music establishment.[79][80] In the September issue of Sing Out!, singer Ewan MacColl wrote: “Our traditional songs and ballads are the creations of extraordinarily talented artists working inside disciplines formulated over time …’But what of Bobby Dylan?’ scream the outraged teenagers … Only a completely non-critical audience, nourished on the watery pap of pop music, could have fallen for such tenth-rate drivel.” On July 29, just four days after his controversial performance at Newport, Dylan was back in the studio in New York, recording “Positively 4th Street“. The lyrics teemed with images of vengeance and paranoia, and it was widely interpreted as Dylan’s put-down of former friends from the folk community—friends he had known in the clubs along West 4th Street.

I first discovered Dylan in the 70s without feeling truly inspired (Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door may have been the first song I remembered first time around), but as I went on to university Dylan became a huge inspiration to me. Ironically enough it began with the Bringing It All Back Home album, and especially a song that got played repeatedly on the jukebox at the Student Union bar. The song was Gates of Eden, and the lyrics probably sound like total nonsense now but at the time filled us with wonderment. What the hell was he going on about? Did we know or care? The words had a prematurely psychedelic feeling:

Of war and peace the truth just twists

Its curfew gull just glides

Upon four-legged forest clouds

The cowboy angel rides

With his candle lit into the sun

Though its glow is waxed in black

All except when ‘neath the trees of EdenThe lamppost stands with folded arms

Its iron claws attached

To curbs ‘neath holes where babies wail

Though it shadows metal badge

All and all can only fall

With a crashing but meaningless blow

No sound ever comes from the Gates of EdenThe savage soldier sticks his head in sand

And then complains

Unto the shoeless hunter who’s gone deaf

But still remains

Upon the beach where hound dogs bay

At ships with tattooed sails

Heading for the Gates of EdenWith a time-rusted compass blade

Aladdin and his lamp

Sits with Utopian hermit monks

Side saddle on the Golden Calf

And on their promises of paradise

You will not hear a laugh

All except inside the Gates of EdenRelationships of ownership

They whisper in the wings

To those condemned to act accordingly

And wait for succeeding kings

And I try to harmonize with songs

The lonesome sparrow sings

There are no kings inside the Gates of EdenThe motorcycle black madonna

Two-wheeled gypsy queen

And her silver-studded phantom cause

The gray flannel dwarf to scream

As he weeps to wicked birds of prey

Who pick up on his bread crumb sins

And there are no sins inside the Gates of EdenThe kingdoms of Experience

In the precious wind they rot

While paupers change possessions

Each one wishing for what the other has got

And the princess and the prince

Discuss what’s real and what is not

It doesn’t matter inside the Gates of EdenThe foreign sun, it squints upon

A bed that is never mine

As friends and other strangers

From their fates try to resign

Leaving men wholly, totally free

To do anything they wish to do but die

And there are no trials inside the Gates of EdenAt dawn my lover comes to me

And tells me of her dreams

With no attempts to shovel the glimpse

Into the ditch of what each one means

At times I think there are no words

But these to tell what’s true

And there are no truths outside the Gates of Eden

There was much more though – the attitude of the man, the primitive film to Subterranean Homesick Blues that predated the video revolution by 20 years, the fact that he made his own fashions and disregarded whatever else was happening in society. That’s cool! He had plenty of dark days along the way, of course – the drug addictions, the alleged motorbike accident that kept him out of the limelight for some period, his marriage breakdown and much more besides, but he kept bouncing back with amazing resilience.

Initially I got BIABH and The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan on cassette tape and played them to death. Both included several bitter protest songs, which at the time appealed greatly (eg. A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall, Masters of War and It’s Alright, Ma (I’m only Bleeding).) In many ways it was the poetry and the protest songs that captured my attention, and not just anti-war stuff, Blowin’ In The Wind or The Times They Are A-Changin’ either. Take The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll, a commentary on racism at a time when it was still dangerous so to do, and before civil rights legislation had been passed.

Back to those two albums. Freewheelin’ is the folkier of the two, taking as its themes several traditional songs and adding updated lyrics. Bringing It shows Dylan could also play and demonstrated his sense of humour, notably the brilliant Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream, a song which begins with a false intro where Dylan realises his band has not joined in and breaks down into hysterical laughter before launching into take 2 – and the rest of the song is every bit as hallucinogenic as the intro! It also proved that not only could Dylan write the most vividly imaginative lyrics and catchy tunes, but could also time a line as well as any stand-up comedian, to the extent that I still laugh when I hear the song to this day.

Soon after I found many more sides of Dylan, particularly through the purchase of albums like Desire and Blood on the Tracks. In many ways these two albums, recorded respectively in 1976 and 75, were the closest I ever felt to Dylan’s genius. Compared to the earlier material (and bear in mind that inbetween he came up with brilliant albums like Blonde on Blonde and Highway 61 Revisited).

By contrast, Desire seemed more mature, more cosmopolitan, angry but without the bitterness of earlier recordings. Dylan had even begun to work in more witty songs based on invented characters. The breadth of material was staggering – from Hurricane, the story of a boxer jailed for murder; via the captivating story of Black Diamond Bay; and a tale of a Mafia hood, Joey; and finishing with a chillingly emotional song written for and sung to his then wife Sara. It even takes in trips to Mexico (Romance in Durango) and Mozambique.

For Blood on the Tracks, Dylan claims the songs were inspired by the stories of Chekhov, though they are sometimes whimsical and portray a range of emotions not necessarily associated with Dylan songs. Here too there is a crazy and bizarre story to act as light relief, in the form of Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts. This might be a tale of robbery and murder but you couldn’t help but like it, and probably smile too. But the one that got most airplay on the radio shows I listened to was Shelter from the Storm, a typical Dylan song structure and lyric, one that I learned and can still quote to this day:

I was in another lifetime one of toil and blood

When blackness was a virtue and the road was full of mud

I came in from the wilderness a creature void of form

“Come in” she said

“I’ll give you shelter from the storm”.And if I pass this way again you can rest assured

I’ll always do my best for her on that I give my word

In a world of steel-eyed death and men who are fighting to be warm

“Come in” she said

“I’ll give you shelter from the storm”.Not a word was spoke between us there was little risk involved

Everything up to that point had been left unresolved

Try imagining a place where it’s always safe and warm

“Come in” she said

“I’ll give you shelter from the storm”.I was burned out from exhaustion buried in the hail

Poisoned in the bushes and blown out on the trail

Hunted like a crocodile ravaged in the corn

“Come in” she said

“I’ll give you shelter from the storm”.Suddenly I turned around and she was standing there

With silver bracelets on her wrists and flowers in her hair

She walked up to me so gracefully and took my crown of thorns

“Come in” she said

“I’ll give you shelter from the storm”.Now there’s a wall between us something there’s been lost

I took too much for granted got my signals crossed

Just to think that it all began on a long-forgotten morn

“Come in” she said

“I’ll give you shelter from the storm”.Well the deputy walks on hard nails and the preacher rides a mount

But nothing really matters much it’s doom alone that counts

And the one-eyed undertaker he blows a futile horn

“Come in” she said

“I’ll give you shelter from the storm”.

I’ve heard newborn babies wailing like a mourning dove

And old men with broken teeth stranded without love

Do I understand your question man is it hopeless and forlorn

“Come in” she said

“I’ll give you shelter from the storm”.In a little hilltop village they gambled for my clothes

I bargained for salvation and they gave me a lethal dose

I offered up my innocence and got repaid with scorn

“Come in” she said

“I’ll give you shelter from the storm”.Well I’m living in a foreign country but I’m bound to cross the line

Beauty walks a razor’s edge someday I’ll make it mine

If I could only turn back the clock to when God and her were born

“Come in” she said

“I’ll give you shelter from the storm”.

There are many more Dylan songs and albums about which I could wax lyrical, but then you have to remember the man has a phenomenal back catalogue and to this day writes incredible songs for which many would kill. I wish him well, wherever he is, and will finish by reminding everyone that this is a man who inspires people everywhere. He inspired the England and Warwickshire bowler Bob Willis to the extent that Willis changed his name to include “Dylan” as a middle name!