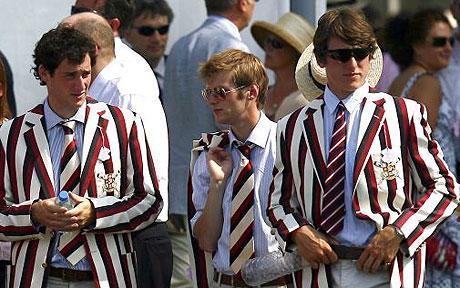

I was in Henley-on-Thames during regatta week, recently. Rowing events notwithstanding, this was clearly a time and place to see and be seen. Men everywhere were out in their colourful stripy blazers and ties, representing one rowing club or other, and those that were not wore navy blazers, cream trousers and panama hats. Women were in long colourful dresses and hats, many utterly impractical for getting about town. Each and every one appeared well-to-do and largely in the upper echelons of British social classes, this being a pastime enjoyed by the higher strata.

Henley happens to coincide with the first week of Wimbledon and the week after Royal Ascot week. A busy time for royalty and toffs in general, it would appear. For while Wimbledon has a public ballot from which names are chosen at random, those with the guaranteed seats and places in the corporate boxes seem to comprise celebs and tennis is generally a richly middle class pastime, in its widest sense. Competitors are from aspirational families who can afford subscriptions to tennis clubs, and competitions attract those who like to be seen. Ascot is famous for its aristocratic roots and the hats affected by ladies also wishing to be seen, and indeed men in top hat and tails. No doubt there are public paddocks, well segregated from the areas populated by the rich, famous and royal. A form of social apartheid, maybe?

The point of mentioning all this was simply that it occurred to me that sport has been and in some cases still is one of the few areas of life where class overrides the democratic sensibilities and need for a broader base. In short, no matter how much spinning goes on about sport being open to all, naked elitism still exists in sport. The LTA makes a big deal of opening new tennis facilities to spot grass roots talent much earlier, but the fact are that the sport does not greatly appeal to working class kids, and often they could not afford the costs of using those facilities anyway.

Ironically, traditionally working class sports have changed significantly. Football used to be the sport where the working man queued up on a Saturday afternoon, but the cost of tickets to Premier League games, and indeed the difficulty of getting hold of them if you are not already a member and season ticket holder, means boxes and any vacant spaces are filled by those on corporate sponsorship junkets or who can find ways to pay top dollar to get tickets. These days, if you can’t afford your sport live you watch it on TV, which means for the addict buying subscriptions to Sky Sports.

Roy Keane famously chided those in the director’s box for their prawn sandwich philosophy, where football used to be a game at which you ate meat pies and drank beer or bovril rather than champagne. For the traditional audience, following your football team to home and away matches means devoting a relatively huge proportion of your income to the sport.

Speedway used to be and to some extent still is a working-class sport, largely ignored by the media in spite of its massive popularity. Sadly, rising costs and bad management have forced the sport into the doldrums, but promoters dare not raise prices to anything like the degree found in football since that would cut off the hard core of spectators that continue to come. Getting into motorsports of any sort for teenagers requires parents who can buy the equipment and support their offspring with transport. The higher the level, the more difficult and costly it becomes for people at the lower end of the scale to compete, unless they can find potential sponsors – and as speedway riders know only too well, the big money goes to the sports with the biggest coverage.

Cricket is perhaps the closest thing to a happy medium in the UK, maybe the result of the gentlemen v players tradition. You could come from any section of society and either play or spectate, and despite the demise of the wealthy amateur almost anyone can join cricket clubs and rise through the ranks. Quite unlike the regimented segregation in apartheid South Africa, for example, whereby whites played cricket and rugby and blacks football. Even now, long after the death of apartheid, that cultural tradition is hard to override; Ntini and Prince apart, coloureds and blacks can break into the cricket team but can’t get access to the coaching or pitches to anything like the same extent their wealthier white equivalents can get.

Talent alone is not enough, and equality of opportunity through schools is just as bad over here – particularly when schools in many of the poorest areas sold off their playing fields, leaving little or no option for students to enhance their sporting skills.

Sport at its best is the ultimate democratisation of society, people competing on merit, but when it is used to emphasise the invisible divisions within society it becomes a weapon to emphasise the inequalities within society. If we want sport to flourish, elitism must end, and sadly the snobbery accompanying many sports in this country means we will probably underachieve in many for a long time to come.