In a recent Facebook status, I said the following in the context of complaints about police abuse in the tactics used to spy on people they deemed to be worthy of surveillance:

In view of two controversies about secretive police undercover operations today, they are undoubtedly necessary in some cases but have licence for abuse by virtue of their lack of transparency and accountability (not even Lord Condon knew when Met Commissioner). In particular:

a) committing of criminal acts while undercover

b) inciting others to commit criminal acts that might never otherwise have taken place (the grounds for many of the successful 59 appeals against convictions gained through this kind of evidence, to date)

c) sleeping with the people you are spying on without revealing true identity, thereby committing a breach of faith

d) selection of groups who were subject to these investigations, often law-abiding and peaceable folk.Must be a better protocol for scrutinising these investigations to prevent malpractice?

But this of course is just one component in a wider debate about policing in the UK that has rumbled on for decades without ever being satisfactorily resolved.

Let’s start with the role of the police. I’ve not been able to find a clear list of duties of police forces, so here is my attempt to define those responsibilities – though I suspect they are in transition and have changed considerably:

- Prevention of personal and household crime by patrolling neighbourhoods, offering advice and working with communities to prevent, including all crimes of theft, robbery, assault, manslaughter and murder

- Detection and prosecution of perpetrators of crime

- Policing of public events of all types to prevent risks to public safety and ensure law and order are maintained

- Attending road traffic incidents and ensuring the rules of the road are applied.

- Gathering intelligence on and prosecuting large-scale organised crime, including money laundering,

- Ditto corporate crimes such as fraud, insider trading

- Liaison with international policing services and forces in other countries to track down crimes going across borders

- Liaison with HMRC’s Customs and Excise service to ensure illegal imports of drugs, alcohol, tobacco and other substances are prevented and the perpetrators prosecuted.

- …and probably much more besides.

This is enforced through territorial forces and a variety of specialist agencies and underpinned by legislation, and, one might suggest, in a climate of low morale, job losses and resistance to change. Over the years various squads have been created, merged and disbanded but the fundamental structure is still the same as it has been for decades.

I was always amused by the roles of Assistant Commissioner, Deputy Commissioner, Deputy Assistant Commissioner and suchlike – you couldn’t make it up in a farce, surely? There is a chain of command and probably well-defined roles and responsibilities, but rising through the senior ranks many of the duties become political and PR-related rather than operational, and often to justify the methods adopted by police forces rather than focus on ways to improve morale and techniques. Given the bloated hierarchy it is perhaps understandable.

Arguably one historical legacy is a huge bureaucratic infrastructure within police forces that have made them slow to respond and slower to act, quite apart from the difficulties of effective engagement with other forces and other agencies – at least up to the point where multi-disciplinary teams involving social workers and suchlike sprang into being. The culture of policing and the criminal justice system has been equally slow to change, particularly around sensitive issues like rape and sexual assault. Now most forces have units for handling victims of domestic violence and sexual crimes with appropriately trained officers, but it took a long time to get to that point. Operation Yewtree, established after the Savile revelations, is a high water mark in the investigation of historical sexual offences, and surely due warning that allegations will be taken more seriously in future.

To put these responsibilities into context, the Peelian principles identify the parameters established by Sir Robert Peel when the original police service was originally devised as the gatekeeper of law and order, and by which they should operate to this day:

Peelian Principles

- The basic mission for which the police exist is to prevent crime and disorder.

- The ability of the police to perform their duties is dependent upon public approval of police actions.

- Police must secure the willing co-operation of the public in voluntary observance of the law to be able to secure and maintain the respect of the public.

- The degree of co-operation of the public that can be secured diminishes proportionately to the necessity of the use of physical force.

- Police seek and preserve public favour not by catering to public opinion but by constantly demonstrating absolute impartial service to the law.

- Police use physical force to the extent necessary to secure observance of the law or to restore order only when the exercise of persuasion, advice and warning is found to be insufficient.

- Police, at all times, should maintain a relationship with the public that gives reality to the historic tradition that the police are the public and the public are the police; the police being only members of the public who are paid to give full-time attention to duties which are incumbent on every citizen in the interests of community welfare and existence.

- Police should always direct their action strictly towards their functions and never appear to usurp the powers of the judiciary.

- The test of police efficiency is the absence of crime and disorder, not the visible evidence of police action in dealing with it.

However, not everything in the garden is rosy. Police forces throughout the UK are beset by problems, many of their own making. Consider this incomplete list:

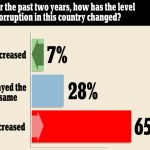

- Corruption in police forces, largely but not entirely eradicated in the clean-up operations instigated during the 80s and 90s. In 2012 there were apparently many officers still being investigated (see here.)

- Falsification of evidence, ditto though processes have been tightened to reduce the scope for some of the bad practice of yore.

- Increasing use and misuse of firearms including the killing of unarmed suspects, not least John Charles de Menezes and more recently Mark Duggan.

- Institutional racism, notably through damning reports from the Lawrence inquiry and subsequent investigations into police corruption, entrapment and behaviour during the Lawrence case. It is, as the Commissioner put it,

- Covering up malpractice and fatal incompetence with lies and manipulation of statements, notably relating to Hillsborough though there are very many more examples on record

- Government cuts and the debate about whether the 43 forces should be merged into a new structure of bigger and, allegedly, more efficient forces, which could potentially change the allocation of officers for community service operations

- Ditto targets and the proposed changes to reduce the amount of paperwork required of the police that may have distracted officers and influenced their attitude towards service delivery.

The key question is whether the police, particularly with Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe in command as Met Commissioner, can rise to the challenge of reform to meet the needs of policing in the 21st Century against a backdrop of crimes changing to evade traditional policing techniques, and in the process regain the reputation for strong ethics, fairness, impartiality and good communication envisaged by Peel. There have been times when police forces have been their own worst enemy, and certainly fallen far short of the best standards, of which heavy-handed operations are but one example. Hogan-Howe has declared a strong intention to restore trust in the police, but when as former DPP says that trust is now no better than in the 1980s, there is a long way to go.

Part of the difficulty is how you prove police have misbehaved when it is the police that are the official upholders of justice, as this blog demonstrates. From 1985 to 2004 responsibility for investigating complaints against the police lay within the jurisdiction of the Police Complaints Authority (PCA), after which it was replaced with the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC). The PCA succeeded the Police Complaints Board (1977-85), before when complaints were handled in their own way by individual forces. The fact that there has been three incarnations of the body responsible for the discipline of police forces tells you that two were deemed to have failed, and did so largely because they were police officers investigating police officers, and did not have sufficient teeth to punish offenders in the unlikely event they were caught bang to rights. Many examples of police brutality went by the board, often for lack of evidence. This in turn contributed to people from the worst affected estates and communities, the ones where police arriving to arrest someone was a daily occurrence, having no confidence in the police or in making complaints. In turn, the poor relationships between police and the bodies arguably impacted the behaviour of a generation. The latest body, the IPCC, is still far from perfect, witnessed by the comments of a parliamentary enquiry into the IPCC’s investigations, copied from Wikipedia:

A parliamentary inquiry set up in the wake of the death of Ian Tomlinson concluded in January 2013 that, “It has neither the powers nor the resources that it needs to get to the truth when the integrity of the police is in doubt.”

Part of the issue is that an initial investigation is conducted internally before the IPCC will look at a case. Then, while the IPCC can sponsor and enforce an investigation, its lack of resources mean that an investigation into one force is often carried out by another force. At no point has there been a process that is both robust and takes seriously allegations with detailed evidence to back them up.

Ah, but the government did introduce elected Police and Crime Commissioners as one means of making the forces more responsive to local needs, though turnouts for the initial elections were the lowest on record. Whether this experiment is working we must wait to see, but I personally have never met nor heard from my commissioner, and I know of nobody else who has ever met their commissioner. These people do have the power to sack their Chief Constable, though I know of no instance where that has happened. In fact, the only occasion I’ve ever read anything said by one of these officials is when that person had to apologise in the national press for offensive remarks made. Hardly a resounding success to date, and certainly not the equivalent to the American system with elected District Attorneys that Mrs May had hoped for. You will also notice a proposed new structure for the police among the photos above, designed to improve accountability, though since the PCC elections the government has soft-pedalled the change process.

I have no doubt the vast majority of policemen do their jobs with strength of purpose and vigour; maybe some will still harbour personal beliefs that are racist, homophobic and/or misogynistic, but I sincerely doubt they are ever as bad as those behaviours portrayed in Filth, even if they have been in the past. However, you would have to be very naive to believe that the problems are restricted to the odd “bad apple,” as often suggested by Chief Constables when their force is implicated. Indeed, over the past 40 years or so senior officers have made concerted attempts to root out corruption and change the culture to stamp out racism and malpractice, but that is still a work in progress. At one time trust in and respect for the British bobby was widespread, where today there is much suspicion and sometimes cynicism and even active hostility, not least when attitudes to detecting crime and apprehending offenders (eg. housebreakers) seems low on the list of priorities, but using speed cameras to gain revenue has never been higher.

There’s no doubt that, like the military, tradition plays a strong part in British policing. The fact that police do not routinely carry guns here is to be applauded, but other aspects of tradition may seem quaint and anachronistic, perhaps less so than the Swiss guards at the Vatican. Bringing policing forward into the modern times has meant changes in tactics and operation of enquiries: from being largely a process of retrospective detection, the police now rely on greatly enhance network of intelligence sources, and indeed on use of firearm squads.

Intelligence is supported by comparative anti-terrorist legislation designed to prevent atrocities from being perpetrated, though it does mean that instances of bad intelligence may well result in the arrest, detention and interrogation for a week or more of innocent people, and contrary to the movies would not simply require an army of snitches but increased use of surveillance techniques and court-approved bugging – though that is largely kept out of the public domain. This intelligence unquestionably includes the undercover work mentioned at the top of this blog; it could be subject to abuse, but done professionally it can and undoubtedly does prevent crimes.

But effective intelligence gathering must be done in the context of protecting the innocent. In the words of John Mortimer‘s immortal creation Horace Rumpole, “there is a golden thread that runs through British justice. Better a hundred men go free than one innocent man be convicted.” From the civil liberties perspective there has always been an issue with use of laws that permit detention on grounds of suspicion, back from when there was the infamous “sus law” enabling an officer to arrest any person they consider to be behaving in a suspicious manner likely to cause a breach of the peace, or to be intending to perpetrate a criminal act.

Where in the 80s people in London housing estates were victims, there may well be paranoia in some Muslim communities that if you are a young male Muslim you stand a good chance of being arrested, and that may have contributed to the radicalisation of young people – just as it did before the 1991 and 2011 riots. Police are very well aware that the mistakes of the past and that their reputation precedes them, which makes sensitivity in handling investigations and arrests all the more critical. By gaining the support of community elders and communicating the reasons for their actions better results have been obtained, but it is still an uphill struggle.

One factor contributing to the difficulty is that the police have yet to recruit anything like enough officers from ethnic minority groups, particularly helpful when the officers in question can speak the native language of local residents to explain what is happening, and to participate in relationship building exercises offering improved security for all. According to the National Statistics on police workforce from March 2013:

There were 129,584 full-time equivalent (FTE) police officers in the 43 police forces of England and Wales as at 31 March 2013. This is a decrease of 3.4% or 4,516 officers compared to a year earlier. There were 6,537 FTE Minority Ethnic officers in the 43 forces of England and Wales. This represents 5.0% of the total police officers, the same percentage as on 31 March 2012. FTE police staff numbers for the 43 forces of England and Wales stood at 65,573, a decrease of 2.8% or 1,899 compared to a year earlier.

In fact, given that officers routinely retire on full pension after 30 years of service, recruiting sufficient fit, active and motivated officers of any origin to fill the gaps may sufficiently difficult that shortages result in some localities, let alone officers of the calibre to be the leaders of tomorrow. More officers will be doing overtime, budgets permitting and criteria for accepting recruits may be reduced.

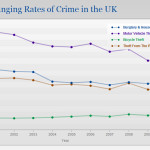

Despite the continued problems listed above, crime statistics are apparently declining. Taken from ONS data:

- Latest figures from the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) estimate that there were 8.6 million crimes in England and Wales, based on interviews with a representative sample of households and resident adults in the year ending March 2013. This represents a 9% decrease compared with the previous year’s survey. This latest estimate is the lowest since the survey began in 1981 and is now less than half its peak level in 1995.

- The CSEW also estimated that there were an additional 0.8 million crimes against children aged 10 to 15 resident in the household population.

- The police recorded 3.7 million offences in the year ending March 2013, a decrease of 7% compared with the previous year. This is the lowest level since 2002/03 when the last major change in police recording practice was introduced.

- Victim-based crime accounted for 83% of all police recorded crime (3.1 million offences) and fell by 9% in the year ending March 2013 compared with the previous year. The volume of offences recorded in this category is equivalent to 55 recorded offences per 1,000 population.

- Other crimes against society recorded by the police (402,615 offences) showed a decrease of 10% compared with the previous year.

- In the year ending March 2013, 229,018 fraud offences were recorded by the police. This represents a volume increase of 27% compared with the previous year and should be seen in the context of a move to centralised recording of fraud.

- Within victim-based crime there were decreases across all the main categories of recorded crime compared with the previous year, except for theft from the person (up 9%) and sexual offences (1% increase). The latter increase is thought to be partly a ‘Yewtree effect’, whereby greater numbers of victims of sexual offences have come forward to report historical offences to the police.

- There were an additional 1.0 million offences dealt with by the courts in the year ending December 2012 (the latest period for which data are available), which are not included in the police recorded crime figures. These cover less serious crimes, such as speeding offences, which are dealt with no higher than magistrates courts.

Some caution should be allowed for the definitions of how the statistics were recorded and compiled, such that not all figures might be on a like-for-like basis with previous years, but it is certain that not all actual crime is reported and/or recorded. Neither does this data indicate whether police detection and conviction rates are improving, which in the last analysis is the data that matters most. Comparing the National Crime Survey to Police recorded data (above), indicates a huge disparity between what people experience and official records.

Nonetheless, the figures could be indicative that police intelligence and presence is enabling more crimes to be prevented, prevention being better than cure from the perspective of victims of crime. Done well, prevention prevents heartaches and saves much valuable police time into the bargain. Long may it continue, but in the meantime I wish Sir Bernard every success in restoring public trust in the police force. If he fails to achieve restored trust we might be blogging about further police failures for many years to come.