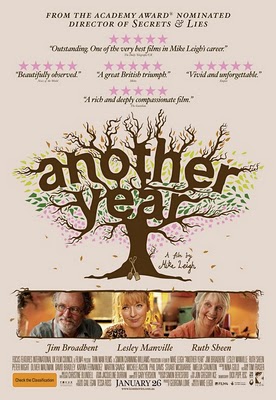

The thing about Mike Leigh movies is that the only real communication is non-verbal; the actual words spoken are largely padding, spoken in isolated non-sequiteurs rather than warm, open conversations, other than as sharp contrast. Critics would say that in most Leigh movies (Topsy Turvy being the honourable exception), nothing happens very slowly, but then some people are pretty shallow, don’t you think?

The other thing about Mike Leigh dramas, on stage or film, devised through months of rehearsal and improvisation, is that actors adore them – and the actor in me would kill to be part of one such production. They/We adore how the camera lingers, allowing them time and space to develop their dysfunctional characters, express innermost feelings and emotions through body language, facial expressions and the use of language in a territorial, Pinteresque way. Actions speak largely of characters misreading the body language and misjudging the situations in ways that are frequently cringeworthy.

But what he does do is give time and space to each cast member, and thereby extracts career-defining performances from each. There are gems wherever you look, any of which characters could have been expanded to tell their stories in their own right.

Another Year is a very simple premise but, as Leigh himself says in the interview thoughtfully provided on the DVD, in execution it is complex, mostly because human emotions are eternally complex and ever-changing. Its theme is that scratching beneath the veneer of jovial suburban banter is a black hole of despair and desolation, and in the process is steeped in poignancy.

The film pans out over a year in the lives of the Hepples, Tom and Gerri (joke!) They are the focal point of the movie and their community; around them revolve a host of beautifully observed cameos. Jim Broadbent plays the geologist and suburban allotment-holder, happily married to Ruth Sheen‘s counsellor and unofficial agony aunt, a woman who attracts every flaky soul within the neighbourhood. They are family people, kind and good, excellent hosts, loyal and true. They are not the catalysts to the disintegrating lives, but the recipients of the raw emotion conveyed all around them.

Broadbent is the perfect character actor. Here, he holds the film together without being flashy or flamboyant, but with just enough cheek and charm – a difficult balancing act, a sort of genial sheet-anchor, a backdrop against which the vivid emotions are played out. But his Tom also plays second fiddle to Sheen’s Gerri, who contrives to be beatific and soothing against the odds. Her Gerri is an earth mother, despite just one child of her own.

The minutely-observed performances start from the very first shot. Imelda Staunton, one of the Leigh repertory company for many years (Vera Drake), provides a masterclass in acting with the face in her role as Janet, a depressive patient in serious denial. She is examined by Michele Austin‘s heavily pregnant Dr Tanya, but clams up and refuses to explain the root causes why she has not slept in months. She wants sleeping pills and nothing more. All doctors have met characters like Janet.

This sets the tone as we then meet Lesley Manville‘s brittle medical secretary, Mary, a neurotic woman who drinks too much wine while speaking volubly about her passions and how her future will be rosy. On and on she goes about how she is strong and independent, contrary to the severe anxiety communicated by her body language. Desperate for acceptance and to belong in the family she never had, Manville’s face speaks volumes, its teary eyes and pinched slit of a mouth. Every decision Mary makes adds fuel to the oncoming disaster, and like true tragedy we can see the inevitability of her fall coming all along.

As the film unfolds, Mary’s mirages vanish like the wind – not least her illusion of a loving relationship with Tom and Gerri’s dutiful lawyer son Joe (Oliver Maltman.) Joe’s body language tells us clearly he does not want the much older Mary, though we only learn his true feelings when he eventually brings home the perky but irritating prattler Katie (Karina Fernandez) – but to Mary this is the bombshell she cannot tolerate but has to acknowledge within the social niceties of middle-class London. There is a lengthy scene where the dialogue continues apace but our attention is drawn solely to the schism exploding within Mary – beautifully drawn! The look of betrayal in her eyes haunts me to this day.

However, the contrast is drawn when Mary rejects the sweaty fumbling advances of fellow-drunkard Ken (Peter Wight), with whom she has much in common but never sees it. She loathes his body shape, and rejects it, though she could have chosen plenty of other reasons. The irony is that she does not see her own many failings in the process.

A word too for the excellent Phil Davis, an actor who never disappoints, whose character turns out to the husband of the insomniac Janet we met in the first scene, but who does not accompany him to the Tom & Gerri summer BBQ in Ken’s honour, possibly in the knowledge that Tanya (with newborn baby) will be there.

Along the way we also meet Tom’s bereaved brother Ronnie (the brilliant David Bradley, memorably also Filch the caretaker in the Harry Potter series), who communicates in monosyllables, and his volatile malcontent son Carl (the aptly named Martin Savage), the contrast between the two sons being played delightfully.

The extended scene between Ronnie and Mary is packed with pathos and humour in equal measure, a scene communicated almost entirely in subtext and facial expressions. The oblique form of non-comprehension between the two seems to speak volumes tell everything we need to know about modern relationships – truly a gem; every serious director should take note.

But this is ultimately Lesley Manville’s movie. She gives a towering performance, one truly worthy of an Oscar nomination, truly deft acting that brings tears to my eyes whenever I see her. The final scene, in which Mary is cracking wide apart but gatecrashes the family party, is truly classic: the hubub of conversation tunes out, leaving just the sight of Mary, alone and in total despair, her mind whirring and her eyes telling the whole story. What more could you ever want to know about the loneliness of urban living?

Another Year is a film of light and shade played out over four seasons, Rohmeresque in its structure and style, though very definitely Leigh in substance and Greek tragedy in form.

Whether, as Leigh suggests, the film is multi-faceted, neither simply optimistic nor pessimistic, it is pretty bleak in its portrayal of the predictable decay of human life, the crumbling facades and the detritus they leave behind. This is a common theme – what people say is not what they think. We, the audience, realise the truth; the characters do not, to their own cost. They are too preoccupied, too wrapped up in the drama of their own lives, to notice what goes on around them.

Leigh has made a rich tapestry of a movie worthy of seeing a second, third and fourth time, with the certainty that with each viewing some new nugget of truth will emerge.

Nothing happens in Mike Leigh’s Another Year — and everything happens

Rather, it’s all in their behavior , the way they get on with their lives — or don’t.

Great review